How to Direct a Super-Short Film from Scratch

By Catherine L. Haws, Student Contributor

Are you curious about making movies, but a bit overwhelmed when you think about where to start?

Right here, right now, I’d like to awaken your imagination on how you can start making a short film TODAY. We’re going to take the pressure off, shoot small, and have some fun.

Go ahead and crack your knuckles (or your neck if you’re one of those people) and get ready!

A quick note about how making a film is different than writing a novel:

Film is a visual medium. The pinnacle of Show Don’t Tell. Audio is also enormously important and not to be thrown aside. I’m sure you are also aware of how films are widely popular and can reach audiences who aren’t habitual readers. Films are part of our everyday lives, and I bet you could list on both hands movies with stories that have impacted you.

Step One: Plan

Your short film must have a plan. You already know the OYAN Elements of Story—give us someone (or something) to care about. Something to want. Something to dread.

As part of your plan, I’m going to give you some boundaries. Like Mr. S says in the Compass at the beginning of the Story Building Section (page 11 for me), having boundaries can be a good thing to focus your creativity when writing a story.

Your boundaries:

- Runtime under 2 minutes total

- No dialogue or narration (doesn’t mean you can’t have sound)

- Plan before you shoot

- Use only 1 room

- Use your phone camera

- Make the audience feel something

If you’re stumped about the prompts and think there’s no way a story can be told in one room with no dialogue, I just followed my own homework and made a film about a sock!

It can be done. (If you want to see the Sock Short, it is linked at the bottom of this post.)

Good. Fast. Cheap.

There’s a saying that movies can only be 2 of these 3 at a time. (If a movie is good and made fast, it ain’t cheap. If it’s cheap and fast, it ain’t good—you get the idea.)

To set yourself up for success with this short film, aim for good and cheap. That means it won’t be fast. Notice when we opened this discussion, I did not say you’d start AND finish your short film today. If this makes you impatient, let’s remember that we’re part of a novel-writing community, okay? We are long haulers!

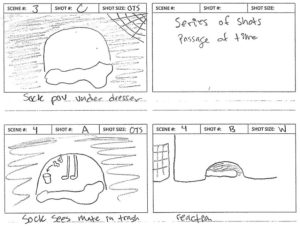

Create Storyboards

Since film is a visual medium, start thinking about how the short film will play out by drawing or taking pictures and putting them in sequence. This is called a storyboard. You can use blank sheets of paper or find storyboard templates online (Studiobinder is a great resource). I like to use ones with spaces to write captions describing what’s going on in the story and if there is camera movement. I find it easier to storyboard if I know the space I will be working with.

You’ve picked your one-room location, right? Now walk around the space thinking of how you will position your camera. How can you make each frame visually interesting?

What do you want to be the first thing your audience sees? Where do you want their gaze to travel next?

Play with holding your camera at eye-level, birds-eye level, and bugs-eye level. How does that change the way the audience feels about the subject? How can you build depth by arranging a background, middle ground, and foreground instead of just a blank wall?

After experimenting like this, how do you need to prep the space before filming?

Well, hop to it!

Step Two: Do

Start shooting! Usually films are shot out of sequence which means that scenes 1 and 5 might be shot on the same day while 2 and 4 are another day. Since your film is taking place in one room, you might need to plan on shooting all the shots facing one wall first and the shots facing another direction second, rather than switching back and forth to match your storyboard.

Check off the shots as you record them to make sure you are getting the coverage you need. If something goes wrong in one take, try again! As you go along, take note of which take you think you’ll use in the final cut, but don’t delete the other take just yet. You might find it useful later. Your storyboard can act as your shot checklist and is also helpful when editing!

Speaking of editing…

Step Three: Finish

This stage is the final leg of the screenwriting journey. You will make millions of choices involving timing, sound, sequence, performance, omission, etc.

Take a breath. Don’t freak out.

Some helpful tools:

- There are some free editing tools out there such as iMovie, PowerDirector, the Splice app, and more. (I have not used PowerDirector or Splice before, so I don’t know how good they are to work with. I just wanted to let you know they are available.)

- If you need to transfer video files from your phone to a computer you can use WeTransfer.com, an SD card reader, or bluetooth.

- Royalty-free music can be found on websites like BenSound.com and sound effects can be found at Freesound.com.

The Art of Editing

If you’ve ever edited a story you know that the final product is always different than the first rough draft. Allow your first cut of the short film to be messy.

I find it helpful to splice together a rough cut matching the storyboard first. Don’t think about the exact timing, don’t think about the music, and don’t think about the Oscars—just align the shots in sequence. Watch your rough cut as a whole. Congratulations! You’ve just identified a million and one changes you want to adjust!

Give yourself time for this process, but also don’t edit yourself into a perfectionistic rut. Have fun, experiment, and don’t be afraid to abandon shots completely. If it doesn’t tell the story well, cut it out!

You might wonder, “How am I supposed to cut down this cinematic masterpiece into only two minutes? Boundaries shmoundaries, why can’t it be 12 minutes?!”

Please, trust me on this.

I might have really loved my socks, but would you have wanted to watch them for more than 2 minutes? I highly doubt it. Sticking to this boundary will force you to evaluate what is important to tell the story and make the audience feel something—and “bored” is NOT what you want them to feel.

If you have someone nearby, ask them to watch what you’ve got and see if they understand what the story is. If they are confused, don’t resort to narration to explain. Rework it until your story comes across, and then be done.

Step Four: Celebrate!

Wow! You did it! You made a short film. Now granted, this little film is not the greatest masterpiece you will ever create, but I do hope it was an enjoyable learning experience.

Go forth and keep creating.

Remember that big, hard things start with small steps forward. Who knows? Maybe now you’ve got the itch and will make some more movies some day!

(As your teacher, I expect to be mentioned in your Oscar’s speech. 😉 )

Maybe now you’ll have a deeper appreciation for movies and linger during the credits to see just how many people work to make stories come to life.

Maybe “Movie” is just another word for “Adventure.”

…

Have you ever dabbled in filmmaking before? How does it differ from writing novels?

…

Example short film by Catherine using the boundaries she outlined in this post:

Behind the Scenes of “Sole Mates”:

Catherine L. Haws is a native of central Ohio who believes even ordinary days hold extraordinary discoveries. With this in mind she has studied inside of a shrubbery, hillbilly tiki torch jousted, and flown a two hour round trip alone for some Fentons ice cream. She graduated from Asbury University, worked behind the scenes at two Olympic games, and recently published her first book I Did NOT Choose This Adventure illustrated by fellow OYANer Emily “Harpley” Steadman.

Catherine L. Haws is a native of central Ohio who believes even ordinary days hold extraordinary discoveries. With this in mind she has studied inside of a shrubbery, hillbilly tiki torch jousted, and flown a two hour round trip alone for some Fentons ice cream. She graduated from Asbury University, worked behind the scenes at two Olympic games, and recently published her first book I Did NOT Choose This Adventure illustrated by fellow OYANer Emily “Harpley” Steadman.