Unforeseen Endings & Other Gifts of a Flexible Novel Outline

This is Part 5 of an ongoing mini-series chronicling the “story of a story”: Daniel’s work-in-progress, a swordpunk novel.

Part 1: What to Do with a Story Idea That Won’t Give Up on You? »

Part 2: When Your “Perfect” Story Falls Flat »

Part 3: Growing a Story from the Spine Out »

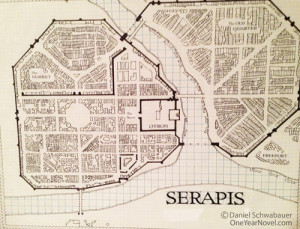

Part 4: Story World Maps: Worthwhile or a Waste of Time? »

…

If you’ve used The One Year Adventure Novel, you know I encourage writers to use outlines. Every story needs structure, however hidden or obtuse, and even “pantsers”—people who naturally write “by the seat of their pants”—can benefit from the pre-defining shape an outline provides.

Of course, outlines aren’t the only way to bring shape to a story. When I started my swordpunk novel, In the Shadow of the Wise, one of the first things I did was create a series of maps.

To celebrate the completion of the book, I asked a friend, Matthias Bryson, to colorize my map inkings. The transformation is a visual metaphor for the whole book.

Take a look at the colorized maps »

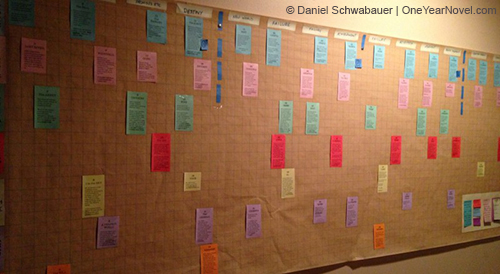

After starting the rough draft in August of 2013, I soon realized I needed some way to keep track of the timeline. The plots and subplots of my seven point-of- view characters—or “POV characters, in novel-speak—overlapped in many places. Making sure their individual triumphs and setbacks matched the overarching story and three-act structure was daunting.

To see everything at once, I tacked an eight foot roll of graph paper to the wall and used colored sticky notes to represent the characters.

This seemed to work at first. But then the sticky notes wouldn’t stay put, so I had to use add tape to keep them in place. That tape made changing the timeline difficult. To move a note meant tearing the graph paper. Before long I realized my timeline was now controlling my flow of ideas. I couldn’t change the it timeline easily on the wall, so it didn’t get changed in my head. My outline had become too rigid.

Another metaphor. Outlines aren’t meant to be followed slavishly. They’re footholds in a story, not the story itself. A good outline will keep you on track when you don’t know where to go next. It will offer suggestions or help you to draw conclusions from other areas of your story or your world. A good outline is like a writing partner who asks the right questions to help you see what you should be doing.

A bad outline will drive you compulsively in the wrong direction. Instead of giving advice, it will give commands. It will tell you to write what it summarizes, regardless of how the story has changed in your mind during the telling. “I am the story,” a bad outline will say. And if you listen to it, your story will be bad too.

Down came the graph paper. (I still have it somewhere, rolled into a tube so it can’t speak.)

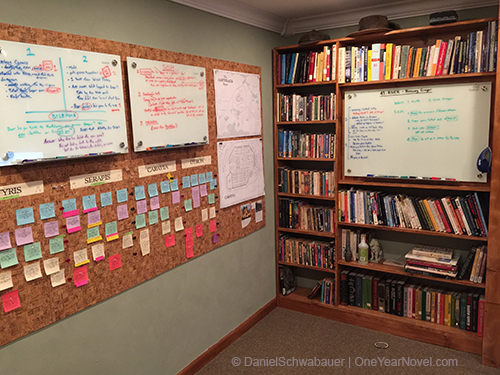

What I needed was a more flexible way of outlining. Something that would allow me to see my whole novel at a glance, while simultaneously giving me the freedom to brainstorm changes on the fly. I needed a combination of moveable and fixed elements, as well as space to brainstorm without damaging existing story structures.

For a while I debated between a huge corkboard and a huge whiteboard, but neither seemed a complete solution. Then I realized I could have both, and the results are what students now see in the background during my webinars.

This solution seems to work for me. It immediately helped me identify that I had too many POV characters. More importantly, it serves as a bridge for ideas. That is, it gives solidity to the various steps of idea formation.

The whiteboards allow me to form—and retain—moments of clarity. They help me to visualize and expand on the chapter summaries from my initial outline. They reveal, in practical, what-would- this-look- like? stages, the flaws in my original outline.

The corkboard gives that outline a flexible permanence. It can be changed easily or left in place as the manuscript develops.

At no point was this more helpful or obvious than early December of 2014. I’d written two-thirds of the novel and was starting to believe that I might actually finish the book!

Then words I didn’t expect appeared on the whiteboard. It was as though my subconscious had taken control, its unseen hand closing over my own to guide the dry-erase marker. No, not like that. Like this. A new story ending emerged, one I had never considered.

I stepped back and stared for a while. Put the marker down. Sat in my chair and pondered.

My corkboard showed 22 more chapters neatly outlined—the rest of my book that still needed to be written. My whiteboard showed two phrases, sketched in an artless scrawl. They would obliterate those chapters and require a total rewrite of the 96,000 words I’d already completed.

A new and different ending than the one I had planned for. Could I do it? Should I do it?

The new idea intrigued me. And because I found it surprising, I suspected readers would too. But was that enough?

Was surprise justification for going an entirely new direction? Or had I just grown bored with the work of writing and let myself be distracted?

Unexpected endings aren’t good just because they’re unexpected. They have to be fulfilling and meaningful as well. The element of surprise is simply what keeps readers from feeling the story has been predictable.

I stopped writing the rough draft. For a whole week I came down to my office to pace and stare at my corkboard . . . and the haunting new words in dry-erase black.

Any ending that wrote itself—anything that felt shockingly unexpected—was either the work of a lazy imagination or an inspired one. But which sort was this? After all this time, was I capable of telling the difference?

In the end, I chose the whiteboard. At some point I realized that the main thing keeping me from writing the new ending was not the nature of the ending itself, but the work required to achieve it. The laziness wasn’t just in my imagination.

This meant re-imagining not just the ending of the novel, but the beginning and middle as well. And of course I can’t know whether anyone else will like the ending. But it feels right. And I’m convinced that genuine inspiration is better and more reliably creative than the pre-defined shape of an outline conceived months or years earlier.

When your subconscious hands you lemonade, don’t ask for lemons.

…

Have you ever diverged from your outline in a way that brought life to the story?

…

Daniel Schwabauer, MA, is the creator of The One Year Adventure Novel and Cover Story Writing creative writing courses. His professional work includes stage plays, radio scripts, short stories, newspaper columns, comic books and scripting for the PBS animated series Auto-B-Good. His young adult novels, Runt the Brave and Runt the Hunted, have received numerous awards, including the 2005 Ben Franklin Award for Best New Voice in Children’s Literature and the 2008 Eric Hoffer Award. His third book, The Curse of the Seer, released in the summer of 2015.

Daniel Schwabauer, MA, is the creator of The One Year Adventure Novel and Cover Story Writing creative writing courses. His professional work includes stage plays, radio scripts, short stories, newspaper columns, comic books and scripting for the PBS animated series Auto-B-Good. His young adult novels, Runt the Brave and Runt the Hunted, have received numerous awards, including the 2005 Ben Franklin Award for Best New Voice in Children’s Literature and the 2008 Eric Hoffer Award. His third book, The Curse of the Seer, released in the summer of 2015.

This is AMAZING and exactly what I needed with my heirloom novel! THANK YOU, Mr. S!!!