Mapping Your Writing Traits

Read Part 1, on the significance of finding your writing identity »

Read Part 2, on the distinction between Wordsmiths and Storytellers »

In my last blog post I suggested that writers tend to be either Wordsmiths or Storytellers. Wordsmiths focus on images created by beautiful words. Storytellers focus on concepts and interesting ideas.

Obviously this is too simple. The Wordsmith/Storyteller (W/S) scale is only one-dimensional, and there is more to writing than choosing good words or finding clever ideas. Furthermore, no writer is wholly one thing or the other. We are each a Wordsmith and a Storyteller—an image person and a concept person. We must be, because all stories require both images and concepts to work.

So I don’t believe in shoe-horning every author into the smallest possible box. But if I want to understand my own strengths and weaknesses, the W/S scale is a good place to begin. Better still is this two-dimensional chart for mapping four traits simultaneously.

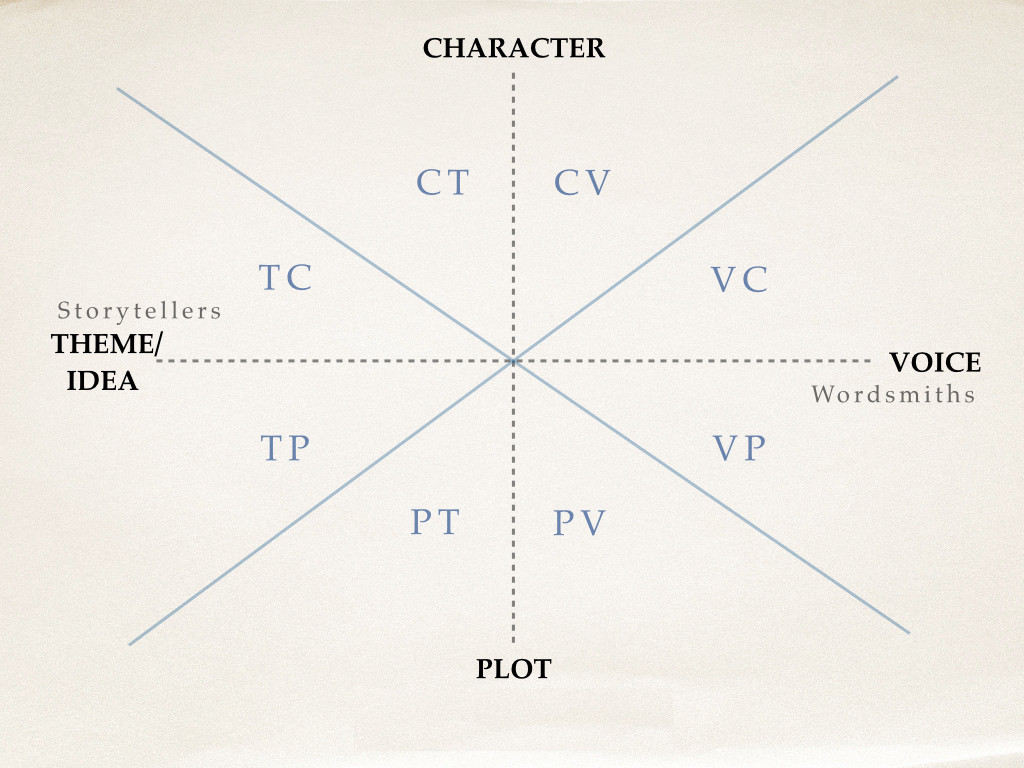

The horizontal axis is the just the W/S scale renamed. Wordsmiths are basically Voice people. Storytellers are concerned more with Ideas and Themes.

The vertical axis is the time-honored Character/ Plot scale. People sometimes talk as though these two categories are mutually exclusive, as if every writer is either a character writer or a plot writer. But of course every writer is both. We just tend to find one easier than the other. Our talents are usually lopsided.

Notice that the chart splits each quadrant down the middle, creating eight areas. The idea is that your tendencies will fall on one side or the other. Even within this quadrant there is dominance.

So, a “CT” writer finds characters easier to create than compelling plots. And she’s more storyteller than wordsmith; she leans towards ideas and concepts and themes rather than imagery and word-play. But the CT writer is not a TC writer. The CT writer leans most of all on her characters. She uses ideas and concepts to round out her story people. She may not even notice her themes until her characters do.

The “TC” writer has the same dominance along each line, but is driven mostly by Theme or Idea. This writer’s characters may be witty or terrifying or fascinating or complex (or all of the above), but whatever they are, they exist because the world of the writer’s Theme gave them air to breathe. The Idea came first, and its people followed.

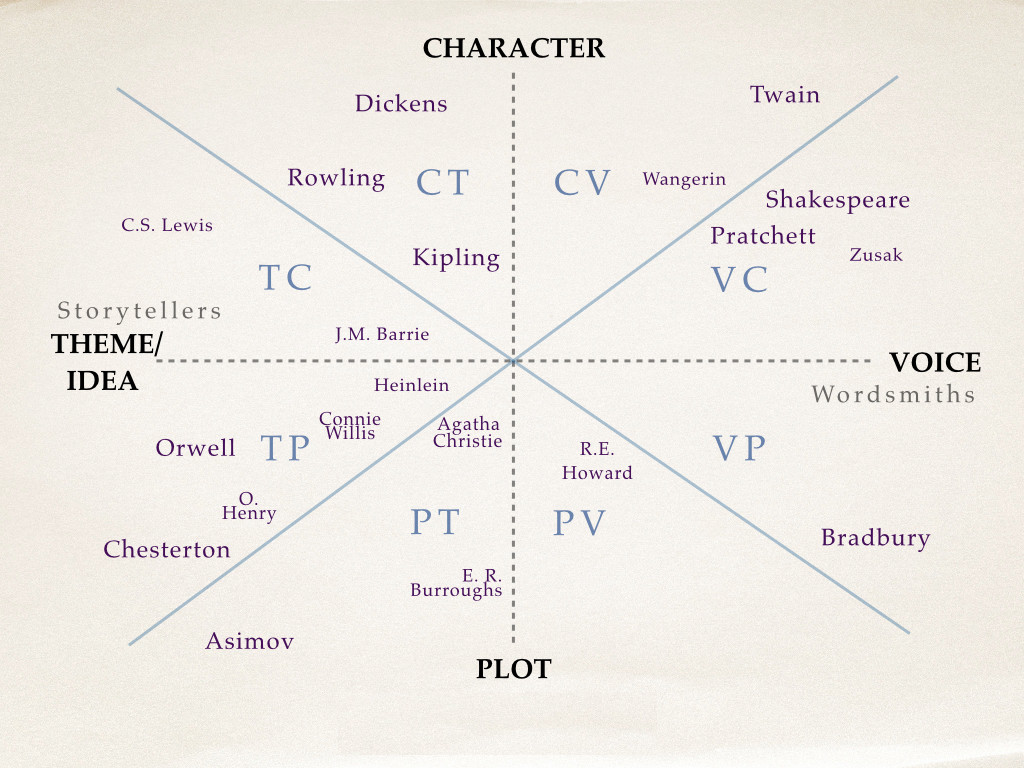

Instead of going through each of the other six types, I’ve filled in the names of some of the writers on the bookshelf next to my desk. My placement of these authors may be flawed, but they’ll serve as examples.

Just because I put Twain in the CV section doesn’t mean I think he was bad at plotting and never had any good ideas. But Twain was more concerned with people than story arcs. And his voice is far more distinctive than his ideas and concepts. In fact, one could argue that his body of work only has one theme: “Aren’t we humans foolish?” But that one theme wears a hundred different faces.

To take the point further, I sometimes ask people which scene in Twain’s books they find most memorable. The answer is always the same: Tom Sawyer white-washing the fence. That scene perfectly captures Twain’s view of human nature, and it does so in his unmistakable voice.

Over in the TP section we find G.K. Chesterton caring much more about Theme and Plot than Characters and Voice. Oh, his voice is distinctive, but that’s not why he’s loved as an author. Chesterton’s superpower is the paradox. He sees paradoxes in everything: in cheese and dandelions and God and marriage and sanity and the search for truth and even in the writing of mystery novels. But paradox is not a theme; it is just the indication of a mind fascinated by puzzles and ideas. His themes range widely, even as his work ranges from poetry to short stories to novels to biographies to essays.

Chesterton cares more about plot than character; his characters exist to make the plot make sense. And his plots exist to give structure to his themes.

C.S. Lewis, who admired Chesterton, is similarly Theme-focused. But Lewis gravitated to characters rather than plot. He didn’t need outstanding characters when he found the right theme or concept. But he much preferred creating interesting people to creating interesting plots. In fact, Lewis often borrowed his plots from others. (For that matter, his characters are often borrowed too).

But I don’t care because Lewis makes me see the world differently. And when he does, it is always through the lens of a character rather than a story arc. Narnia changed me not because I saw a lamppost or wardrobe or a country where it is always winter and never Christmas. Narnia changed me because it introduced me to Aslan and Reepicheep and Puddleglum.

Where do you fit?

Most of us are prone to misdiagnosing ourselves. To really understand your own strengths and weaknesses, you’ll need feedback from beta readers. You’ll need the opinions of people who have read a lot of your work and are willing to talk to you honestly about it. Most of all, you’ll need to appraise your own talents fairly. What do you do well? Where do you fit on these two scales?

Keep in mind that your talents and abilities will change over time. Whatever insight this chart provides will be mostly a snapshot of your skills at the moment. The advantage of quantifying them now is that it can help you decide what sort of writing you are best suited for.

Don’t waste time trying only to perfect your weaknesses. Instead, hone your strengths. We don’t read Twain for plot. We don’t read Chesterton for character. And readers won’t buy your books because you made your weaknesses slightly less bad. Concentrate on becoming a rockstar at your dominant skill.

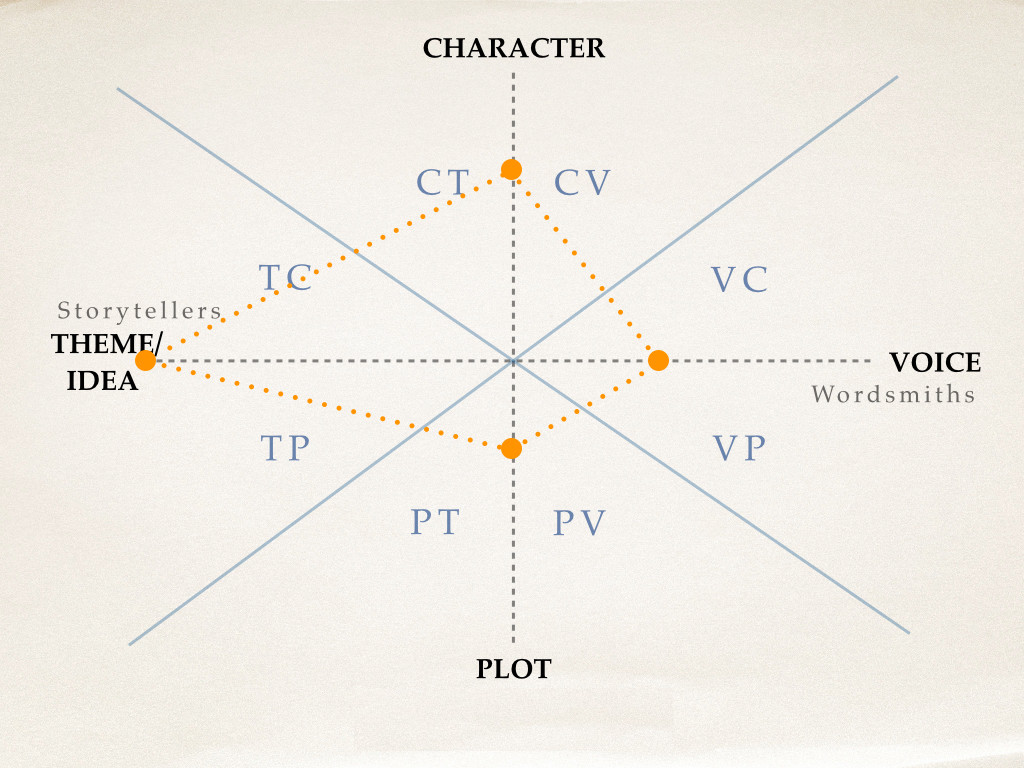

To place yourself on this chart, give yourself a score from 1 to 10 in each of the four elements. A writer who scores out at Theme [9], Voice [3], Plot [2], Character [7] would be a TC.

Wherever you place yourself, this chart will still be a vast oversimplification. But perhaps it will lead to a little self-reflection and deeper insight into the sorts of things you are really passionate about.

In the end, of course, self-analysis is no substitute for the act of creation. Finding your writing identity will always be more about writing than making charts.

…

Into which of these sections would you place yourself?

…

Daniel Schwabauer, MA, is the creator of The One Year Adventure Novel and Cover Story Writing creative writing courses. His professional work includes stage plays, radio scripts, short stories, newspaper columns, comic books and scripting for the PBS animated series Auto-B-Good. His young adult novels, Runt the Brave and Runt the Hunted, have received numerous awards, including the 2005 Ben Franklin Award for Best New Voice in Children’s Literature and the 2008 Eric Hoffer Award. His third book, The Curse of the Seer, released in the summer of 2015.

I’ve been enjoying reading this series! Focusing on your writing strengths rather than your weaknesses is a concept that I really took to heart at the SW last year. I think I’d put myself in the CT section. I’m definitely a character-driven writer, with a love of strong themes (although they don’t always turn out the way I want them to!).