Kebeth the Aleut

Episode 16 •

Kebeth the Aleut

• Alaskan Indians paddling in their baidarkas or clustered at camp fires in their cedar forests are telling with awe the strange tale of Kebeth, the Aleut.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Email | TuneIn | RSS

SHOW NOTES ____________

Kebeth the Aleut

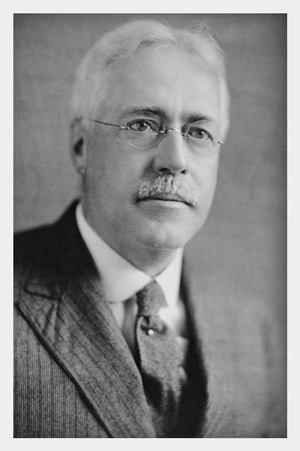

By Frank Vanderlip and Harold Bolce

THE TRUE STORY OF KEBETH, THE ALEUT.

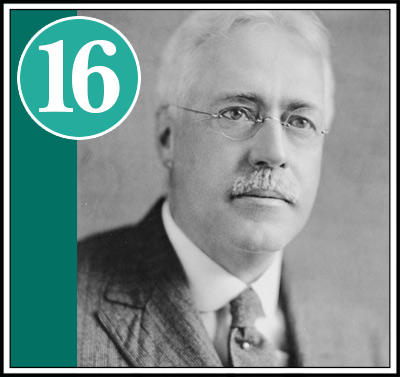

Why President Mckinley was petitioned to save a murderer from the scaffold.

Still the world is wondrous large, —seven seas from marge to marge—

And it holds a vast of various kinds of man:

And the wildest dreams of Kew are the fact of Khatmandhu,

And the crimes of Clapham chaste in Martaban.

—Rudyard Kipling.

ALASKAN Indians paddling in their baidarkas or clustered at camp fires in their cedar forests are telling with awe the strange tale of Kebeth, the Aleut. Eskimos meeting on the ice-pack pass along the amazing story and recount its tragic details as they huddle around their stone lamps of sputtering whale oil in their underground igloos beyond the Arctic circle.

The grim incidents of his crime and the riddle of his voluntary martyrdom are equally treasured, and he who can boast of having roamed over frozen mountains with this mighty hunter or sailed with him on any of his annual returns in his pelt-laden umiak to the trading posts of the white men on Kotzebue Sound, or Bristol Bay, is himself a hero in the eyes of his native comrades. President McKinley, too, comes in for a liberal share of their admiration, for it was the Great White Umialik at Washington (the Father who sends the revenue cutter “Bear”) who, on the 16th of November, 1900, wrote the climax of the story when by his signature he struck from the path of the principal actor in the plot the shadow of the scaffold. It is true that the gray walls of life imprisonment were substituted, but with Kebeth saved from the ignominy of execution, his romance, among his brethern, becomes immortal.

“The circumstances in this case,” said the Attorney General in his memorial to President McKinley, “are most extraordinary, and deserve a special chapter in the annals of remarkable crime.”

The prisoner now beginning his life sentence is declared in the official papers to have been “one of the most reckless, dangerous, and fearless Indians in Alaska.” In the typewritten record of the trial which the court forwarded to the White House, Kebeth is set down ingloriously as “Jim Hansen,” for tinder that commercial alias he bartered his skins and furs and walrus ivory.

Kebeth, the Swift, his Aleutian tribesmen call him. He was a famous hunter. For a decade, tales of his prowess have been repeated from Sitka Bay to the Isthmus of Pernyu.

He was a prodigious rover. He plied his calling from the Aleutian chain and the Kadiak Archipelago, to the far desolations around Point Barrow. His skill in hunting the sea otter on the shores of native, islands is recalled with pride by his people. At Cook’s Inlet and at other coast points he was known as the Brown Bear, from his success in hunting that animal. Kebeth did not share the tradition of his tribe that the brown bear is an Indian in the disguise of a bear. Ages ago, before his people abolished the office of native ruler, a beautiful daughter of a chief, according to the legend, coming across bear-tracks in her path, spoke contemptuously of that animal, and, for her indiscretion, was beguiled into the brown bear’s lair and forced to wed that shaggy creature. To her the bear confided his great secret, and she in turn- warned her tribesmen to spare her ursine progeny. But Kebeth was not impressed by this tribal myth, nor did he, as some of his fellow-hunters who also defied the tradition, atone for his slaughterings by first addressing compliments to the intended victim, a performance which to the savage conscience of the Alaskan expiates the sin of the killing.

During the hunting season Kebeth and his followers would work up over the ice-pack, bagging black bear in the St. Elias Alpine range, harvesting lynx, and martin, and black fox, from the fastnesses of the upper Yukon, and the white fox along the Kuskoquim River, and then press on to the polar wilderness. Arctic blizzards did not intimidate these native hunters. When melted snows began to run out on the sea ice, indicating that the long winter was about to relax, Kebeth and his hunters would build them an umiak, or skin boat, with a framework of cedar lashed by seal thongs, and the whole covered with the skins of walrus artfully sewed and pulled tight. In this strange craft, which storms cannot imperil, the hunters sailed back across Kotzebue Sound and sold their fox, bear, mountain goat, and reindeer skins to the Kablonas, the white men who have whiskey and tobacco and gold, treasures seemingly as indispensable to Alaskans as they are to some of the most civilized of mankind.

With the long chase ended and their trophies sold, their goat-skin purses filled with gold, their puksaks of wolverine fur bulging with tobacco, and their canteens of sealskin brimming with unholy brews and distillations, the happy hunters would begin their annual riot.

Sometimes they had their saturnalia at Juneau, sometimes at small Eskimo villages, but of recent years Skaguay, with its population of adventurous gold-seekers, its dives and dance halls, seemed to offer superior /acilities, and there Kebeth and his crew celebrated their holidays. At such times, while not transgressing the license which serves for frontier law, these rude hunters were greatly feared, their leader particularly, and even white men noted for their scorn of sudden death, treated him with discreet civility.

On his hunting expeditions and in his annual carousals, Kebeth’s most beloved comrade was Artikoor, the Silent, a kinsman noted for his imperturbability, his restraint, and his wholesome influence over Kebeth. But for Artikoor, the daring leader would long ago have been implicated in serious crimes. It was Artikoor who gave timely warning and by his example kept the savage revelry within certain bounds. Artikoor was also skilled above all his fellows in ice-craft. In the knowledge of the habits of Arctic game he had no superior.

Early in the fall of 1899 Artikoor sought to wind up the season’s revelry. “The walrus,” said he, “swims to his winter seas, and the ptarmigan and kiraion, the gray plover, fly to their distant homes. Let us, then, leave the kasheem, the house of dancing, to white men and their women.”

For once, however, the seductions of a Skaguay vacation overcame the laconic suggestions of his kinsman, and Kebeth refused to rally for the expedition. Without further word Artikoor provisioned a small craft or kayak, and, taking his wife, Shucungunga, and their child, started on a little trip, intending, it is supposed, to shoot a few eider ducks and ptarmigan, and with this game, on his return, to rekindle in his drunken leader his old-time love of the chase. In fact, to Un-a-hoots, one of the hunters, Artikoor intimated that such was his purpose.

When Kebeth realized that Artikoor was gone, his thirst for pleasure was suddenly cloyed. For several days he sat as if dazed. When a week passed and no tidings came from his comrade, Kebeth, thoroughly sobered, resolved to try to find him. While making preparations, an Indian brought word that he had seen a fragment of Artikoor’s kaiak on the beach of Lynn Canal.

Now a council of war was held. It was decided that the Kablonas, knowing that Artikoor never spent all his gold, had murdered him and his family. That he had perished in a storm was absurd, for he was master of the winds and tides. He knew every reef. In his hands, his kaiak was as certain as the stars.

With the Indian who had brought the story, Kebeth’s band moved up the coast. True enough, there on the sands at the edge of a deep wood lay the broken cockpit and some whalebone lashings of Artikoor’s kaiak. A few feet beyond, half covered with driftwood, was a part of one of the missing man’s mucklucks, an ancient bone spearhead which he had worn as an amulet, and a copper bracelet from the wrist of Shucungunga.

With a savage oath, Kebeth declared vendetta against the slayer of Artikoor.

No sordid compromise would have appeased this resolute hunter. Bravery and romance were in his blood. In that cockpit in which Artikoor had stoically steered to his mysterious death Kebeth read his duty to sail every sea, and in the torn fragment of mucklucks in which his sturdy comrade had stalked across glacial hunting-grounds he beheld the summons to explore every forest and every wilderness of ice until he should find his foe.

There was no riot of anger in his resolve, and it is a matter of record that from the moment he dedicated himself to maintaining this stern ideal of his people, he tasted no liquor nor indulged in any form of license. His determination to take the life of the slayer of his kinsman was, to him, the holiest impulse he had known.

But how was he to find his enemy? It was one thing to bring out of the ice-wilderness the pelts of furred beasts; it was a far more difficult game to stain his knife with the blood of an unknown enemy.

Kebeth felt the need of a divination keener than the huntsman’s, and, taking the melancholy mementoes of his friend, he returned with his band to his native village and besought his shaman.

A solemn session was held under the shadow of their totem pole, crowned with a crude effigy of the raven, the tribal emblem. The shaman, dressed in piebald wolverine skins, presided. Translating the curious and ancient carvings on the totem pole, the native priest declared that Kebeth was one of the chosen members of the tribe; that he was descended from men who had hunted the mammoth caligabuk, and even from more remote hunters who, before glaciers plowed the Arctic valleys, had followed the aurocks through forests of tamarack. Now a great thing had come to him. He was to fulfill the promise of his lineage.

“Go,” said the shaman, “to the spot where you found the possessions of our brother, for as the tern’s bill in the whalebone lashing of the seal spear causes that weapon to strike like the tern upon its prey, so shall this charm of crimson jasper which I give you bring the slayer of Artikoor to Kebeth’s feet.”

He further directed Kebeth to hang the amulet side by side with Artikoor’s on a limb within sight of the place where the belongings of the missing hunter had been picked up, and, hidden behind bushes, to camp there.

“Within thirty sleeps,” prophesied the seer, “the murderer will return.”

So Kebeth and his followers established their camp and began their criminal vigil on the shore of Lynn channel.

At this time a young man of Skaguay was planning to enjoy, with his bride, an outing in the beautiful woods along the channel. Here is the Attorney General’s story of their fate:

“Sometime about the beginning of October, 1899, Burt Horton and Florence Horton, a young married couple, residing at Skaguay, procured a boat, and, putting into it a tent, guns, and provisions, and a few necessary articles of clothing and camping equipments, started otf from Skaguay with the avowed intention of camping for three or four weeks, and of fishing, hunting, and prospecting. Burt Horton was some twenty-seven years of age, and his wife about nineteen years of age. They had been married about a year. These people were never again seen alive by any one except their murderers.”

Kebeth and his hunters, from their hiding-place, saw Horton’s craft approaching. “Vengeance is mine,” murmured the hunter, “the Kablona brings his woman.”

With a quick turn of the tiller, Horton sent the prow of his boat deep into a shelvingbank. A miniature avalanche of loose earth struck the water, sounding like clods on a coffin.

Horton set to work to carry their blankets, tents, and provisions ashore. His wife, picking up a stick, wrote their Christian names in the beach sand, and in that act traced their epitaphs.

“She is looking for Shucungunga’s bracelet,” whispered the Aleut.

Now she ran to help her husband. Fire was started, and they were enjoying their coffee when rifle shots and savage yells shrieked through the woods.

Horton tried to leap to his feet, staggered, and fell on his face, dead. His wife, mortally wounded, extended her arms helplessly toward him.

The savage hunter and his grisly butchers were upon them.

With a knife he had inherited from his fathers, and which was subsequently produced in court—a savik of gray flint with handle of reindeer antler—Kebeth vengefully slashed the dead miner.

“Here, Son of the Raven,” he then cried to one of his hunters, “you knew Shucungunga; avenge her death.”

As bidden, the Indian, who figured in the trial as “Jim Williams,” cut the young woman’s throat.

They buried the bodies in the sands at the skirt of the woods.

Kebeth returned to the shaman, displayed his blood-stained savik, and related the details of his crime.

“Well done, brother,” said the man of mystery, “but go not again on the chase until kinalin, the king duck, returns to the north, for Orca, the demon of the deep, lurks for you in the storm, and Kajariak, the evil master of the kaiak, rides in the cockpit, and T’kul, the wind spirit, prowls for you on polar mountains. Go back to the city of the Kablonas, for greater things yet shall Kebeth, Son of the Raven, do.”

Pondering this strange command, and moved by unaccustomed forebodings, Kebeth, accompanied by his impenitent band, returned to Skaguay.

They were still rich in gold, but Kebeth ordered that there should be no more dole or drink. Kebeth moved like one in a dream, walking erect, looking neither to the right nor the left. Residents of Skaguay, accustomed to the delirious lawlessness of the hunter, noted his sobriety, the manliness of his walk, and the dignity of his speech.

“The Brown Bear,” they said, “has reformed.”

Some of his followers, whose thirst had not been appeased by the sacrifice of blood, demurred at the temperance regime, but the leader was inflexible, commanding them to abstain yet a while, lest, by succumbing to the habits of the white men, they dim the glory of their savage deed. Kebeth’s law was not questioned. He had ever been the master of these men ; now he was to them a moral hero, as well.

One night, as the lights of the saloons of Skaguay began to gleam, to lure wayward feet, Kebeth and his hunters were attracted by the sounds of singing and the beating of tambourines. Looking, they saw a little company of men and women in queer costumes. They sang, shouted, waved their arms, and beat their instruments. In front a man carried a banner.

As the Indians gazed, the strange company paused, knelt on the unpaved streets, and prayed. Then Adjutant McGill, of the Salvation Army, began to address the crowds that had gathered. He, in the once ridiculed methods of his strenuous organization, was seeking to reform this frontier city, where human life was held less sacred than gold dust.

His text was Barabbas, and he told the story in language that a wayfaring man, though an Indian, might not err therein.

“Life,” he exclaimed, ” is a glorious thing, but to die for a principle is sublime. Who would not rather die with Christ than live with Barabbas? Men of Skaguay, what master do you serve? Do you follow that redeemed host that marches under the fadeless banner of the Star of Bethlehem, or do you shamble with the rabble that clamors for the release of Barabbas, whose hands are red with human blood?”

Kebeth was visibly affected, but whether by the exhortation or by the music, he could not tell. The music, however, was not strange to him, for the kelyau, the one musical instrument of his people, is, in truth, a tambourine. Even the tunes were not new, for Adjutant McGill had adopted the melody of dance-hall ballads which the Indians, like all the inhabitants of Skaguay, had heard for a price. The words, of course, were novel.

Kebeth followed with the crowd to the “barracks.”

He was as one who had excavated a buried city.

‘God’s mercy,” he heard the leader say, “is wider than the sea. Come, men of Skaguay, renounce your sins and follies.

“You get some gold, dug from the mud,

Some silver ground and crushed from stones.

Your gold is red with dead men’s blood;

Your silver black with oaths and groans.”

“But know that, though your hands are crimson with crime, they may be white as snow.”

“Hallelujah,” cried a sweet-faced girl, striking a tambourine. There was a general shout from the army, and then more songs, prayers, and pleadings. There was much excitement. Above the confusion of tongues, Adjutant McGill’s voice, urging sinners to repent, was like a bugle blast.

Several visitors, moved by a similar impulse, responded to the invitation to step forward, Kebeth among them. A policeman of Skaguay, believing the Brown Bear full of strong drink, thought to avert a race riot by putting him out. “Let him come,” cried the Adjutant; “for the least among these, my brethren, is greatest in the kingdom of God.”

Kebeth passed to the improvised altar. His braves remained in the seat of the scornful.

“What is your name, my brother,” said Adjutant McGill, extending both hands.

“Barabbas,” replied the hunter.

“Glory be to God, who saveth even to the uttermost,” exclaimed the Adjutant. They prayed together, and together they mingled their tears.

That night Kebeth went home rejoicing. The defiant joy he had felt as a savage, glorying in a murder commanded by the customs of his people, had been supplanted by an ecstasy such as he had not felt since the first years of his budding manhood, when, pure of heart and rejoicing in the thrill of innocent victory, he gathered his harvests from the ice-swept trammels on his native coasts.

His men, fearing their leader had become possessed, had hurried home and were holding a council when Kebeth returned. He glanced at them benignantly, knowing what was in their minds. As he knelt to adjust his blankets of deer skins and furs, he said something which sounded very much like “Hallelujah.”

He was up early the next morning, and his clansmen watched him curiously. First he went out and cut a willow sapling, whittling it into a flat strip about five feet long. This he bent until the ends met, joining them by a band of walrus ivory, stitched to the under side of the slat with black whalebone, thus making a hoop. From a store of miscellaneous skins, ivory teeth, antlers, and amulets in his lodge, he took the dried peritoneum of a seal and stretched it over the hoop, fastening it taut with sinew braid.

“Kebeth makes a shaman drum,” observed Un-a-hoots.

“No,” replied the hunter, ” the Son of the Raven has become the Son of God. To-night I shall sound this kelyau on the streets.”

His followers, disturbed and mystified, held a secret session, to which the leader was not invited, a revolutionary performance without precedent in the record of their nomadic association. Kebeth’s conversion to Christianity was costing him his dominion over savage flesh and blood.

Then Kak Klanat spoke, addressing the leader. “You know,” said he, “that we are your friends, your slaves. In my home on the Island of the Four Mountains, they say Kebeth has bewitched his hunters. Where you go, we follow. But now you adopt the white man’s mysteries; you turn priest. Kebeth, the Swift, we worship, but must I remind our brother that it is unlawful for an Aleut to kneel at the shrine of two shamans?”

“Your shaman is my shaman no more,” said Kebeth. “In his lips he wears labrets of bone and porphyry. My lips shall speak glad tidings.”

Later in his experience, after the Salvation Army had taught him the messages of the Gospel, Kebeth would frequently compare himself to the shaman who had now become to him one of a counterfeit priesthood. “The shaman,” he would say, “deals in many signs and many wonders. I have but one sign—the sign of the Cross. On his head he wears the foolish kabru, covered with the teeth of mountain sheep. They rattle as he dances. I wear the crown of thorns.”

That day, Kebeth, armed with his tambourine, presented himself at the Salvation Army barracks. There was much rejoicing and many songs of praise. That night he marched with the army, beating his kelyau with much power, and joining lustily in the hallelujahs. The Adjutant was profoundly impressed by the conversion of the Aleut, and, after the services, read and explained to him the story of Paul’s illumination while on the way to Damascus.

When Kebeth returned to his cabin, he found it deserted. It had been solemnly agreed at the time of the murders on Lynn Canal that if one of the band confessed, the others would conspire to fasten upon him the entire guilt. His brethren, believing him demented, feared for their liberty, and had taken the trail to the north.

The news that the Brown Bear had turned lamb and entered the Christian fold astounded Skaguay, and, in consequence, the Army’s audience the next night congested the streets.

With sudden inspiration, Kebeth addressed the crowd. In short sentences, picturesque with imagery, he told his story. His people had taught him to dance to the Aurora, and to veil his face behind the wooden mask and gorget when he prayed. But now, although his feet were still in the dirt and the tundra, his head was uncovered to the stars. Once the kelyau sounded to exorcise the Umiarissat, the demons of forest and stream; now he heard in the tinkle of the timbrel and the thunder of the drum, the voice of God.

The Skaguay crowd will not forget the “testimony ” and exhortations of the Indian, but, unfortunately, no faithful record was kept of his rugged eloquence. Only the memory of its power remains. Some nights he would tell them, as no man had told it before, the story of St. Paul’s experience, and would add: “I, Kebeth, called the Brown Bear, an Indian known to you, a man of sin, have seen that Light and heard that Voice.”

Knowing his former reputation as a bad and reckless Indian, no man dared tell him he was insincere, nor was there such belief.

All Skaguay confessed that the Salvation Army had struck pay-dirt in its conversion of Kebeth.

“With that wild Aleut converted,” one miner was heard to say, “Skaguay may be represented in heaven yet.”

“Wouldn’t be surprised to hear that Soapy Smith is twanging a harp somewhere near those regions, now,” said another.

But Kebeth, though he was making a great hit, was sorely troubled. His crime haunted him, and finally he broke down and confessed the whole horrible story to Adjutant McGill.

That good man had feared that some such revelation was impending and was not unprepared. The night that Kebeth had come forward, saying his name was Barabbas, had not been forgotten, but he had hoped that it was the metaphoric trend of the native’s mind rather than the presence of appalling crime that had prompted his adoption of the title.

“Christ Jesus died for the sins of mankind,” sobbed Kebeth. “Let me, a despised Indian, show the world that I can die for my own.”

Acting upon the Adjutant’s advice, Kebeth recited the details of the murder to United States Deputy Marshal Tanner, and led that officer and Judge Sehlbrede and a posse of citizens to the burial-place of Bart Horton and his wife. Snow had fallen, and the shores of Lynn Canal were covered to the depth of ten feet, but the hunter led them without a misstep to the spot. Digging down, they unearthed the bones of the bride and groom.

Attorney General Griggs, in his official statement of the case, says that the hunter, at the time he made his confession, and when he led the officials to the place of tragedy, and throughout the ensuing trial when his testimony was complete and self-accusing, had no other expectation than that he would be executed for his crime.

“He frequently stated,” adds the Attorney General, “that he desired to suffer death as an example to his people, with the hope that it might tend in the future to better their condition and prevent them from committing similar crimes.”

Kebeth hoped that his execution would fully expiate the crime, but, of course, a trial was held, and his accomplices brought to justice. They were gathered from the four corners of the Arctic. They invoked much money and considerable influence in their defense, and tried desperately to shift full responsibility to their fallen leader, who, while more than willing to assume the whole blood-guiltiness, could not keep them in their cross-examination from betraying their complicity in the crime.

The court-room during the trial was crowded by Indians and Eskimos from all parts of Alaska. The fame of the leader, his marvelous conversion, and his sensational disclosures were absorbing themes even among the white population. To the natives the whole affair was a festival of no common order. Ten of Kebeth’s Indians had been indicted. Six of them were convicted and sentenced to terms of imprisonment varying from twenty-three to fifty years, the penalty Kichitoo must pay for having shot Mrs. Horton. Jim Williams, who cut her throat, received a similar sentence. For turning State’s evidence, some of the Indians were released. Melville C. Brown, Judge of the United States District Court, presided. In joining in the petition to President McKinley to save Kebeth from the gallows, he says:

“His entire conduct during the several trials of the other individuals, as well as his own, convinced me of the honesty of his confession, and the purity of the motives that induced it.

“That he was moved and controlled by-a high religious fervor there can be no doubt.

“In the last act in the drama, when I reluctantly passed sentence of death upon him, in answer to the usual question, why sentence should not now be pronounced upon him according to law, he answered, with undaunted heroism, a benignant smile upon his face:

“‘My brother, I have done my duty, now do yours.’

“Such rare fortitude I have never before witnessed.”

The sentence of death was pronounced, and Kebeth was led away to await execution. Every one in the court-room, including the honorable judge on the bench, was affected to compassion. Seamed and grizzled miners, who had held unflinching roles in bar-room fights, where pistol shots punctuated profanity, hurried away to hide feelings they would not willingly betray, and at near-by saloons sought to reassure themselves that their sympathy for their Indian brother had not resulted in any unmanly incapacity for drink.

Even the stoic Indians and Eskimos were, in some instances, moved to tears.

Now a most remarkable expression of public sentiment took place. Judge Brown, United States Marshal Tanner, the District Attorney, the clergymen of Alaska, its editors, physicians, lawyers, and merchants joined in a petition to President McKinley to spare the life of this self-condemned Aleut.

“This Indian,” said the trial judge, has done much for the cause of justice in Alaska. To hang him would, in my opinion, be unwise.”

The Attorney General supplemented this petition by stating to the President that, while under ordinary circumstances the subsequent repentance and confession of a man guilty of so savage and cold-blooded a murder as this ought not to save him from the extreme penalty of his crime, the circumstances in this case were of such an unparalleled character that precedents and conventional ideas of justice could not apply. Mr. Griggs dwelt upon the fact that Kebeth, when he planned and committed the crimes, “was only an unenlightened, unchristianized savage, presumably unmoved by the high moral instincts that guide and control civilized people; and that as soon as his conscience had been enlightened by the moral teachings of a Christian society, with a rare devotion to the standard of duty which his Christian conscience had raised up in his heart, he made immediate disclosure and confession of his crime, and submitted himself to the hands of the law, to abide its judgment.

“Clearly,” added the Attorney General, “he ought not to go without punishment, but, in my judgment, it should be something less than the extreme penalty of the law. I think his sentence can wisely and justly be commuted to imprisonment for life, and I recommend that that action be taken.”

By heeding these memorials and saving this converted Indian outlaw from the scaffold, President McKinley has given to the natives of Alaska a hero whose glory will grow as the years advance. Though ignorant of the classic ideals preserved in the story of the contest of Zeus with the Titans, Apollo’s conquest of the Python, and in other civilized fables, they have drawn on ivory, and carved in stone, and on their totem poles, mythic representations of giant Indians and Eskimos who, for their people, fought valiantly with the demons of earth and air. And there is Delfa, daughter of the Spirit of the Winds, who, by a supreme sacrifice, brings the Sun annually to melt the frozen earth of the North. With these, and above them all, Kebeth, the Aleut, will be canonized in the imagination of these tribes, and though he will end his days in the Federal prison at McNeil’s Island, his life-work as a reformer has just begun.

The prophecy of the shaman under the Totem of the Raven in the native village of Kebeth has been fulfilled.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

By subscribing, you will automatically receive the latest episodes downloaded to your computer or portable device. Select your preferred subscription method above.

To subscribe via a different application: Go to your favorite podcast application or news reader and enter this URL: https://clearwaterpress.com/byline/feed/podcast/