The Tammany Commandment

Episode 17 •

The Tammany Commandment

• A crook has got to look out for himself, and I didn’t trust any gang to take care of me.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Email | TuneIn | RSS

SHOW NOTES ____________

The Tammany Commandment

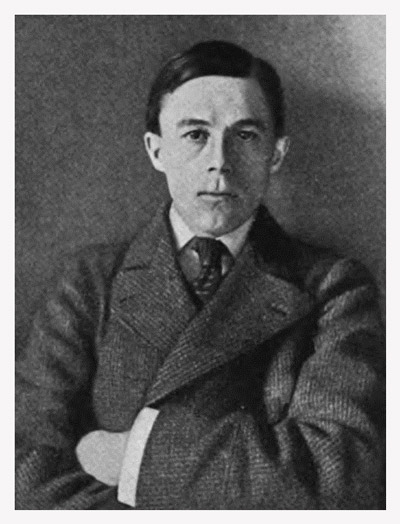

By Josiah Flynt

[The following article is a record of actual conversations with keepers of dives in New York City, most of whom were once notorious criminals, and some of whom were friends of “Jim,” Mr. Flynt’s guide during this investigation.

The reader will keep in mind that “Jim” is one who has “squared it” and is now a respected member of the community in which he lives.

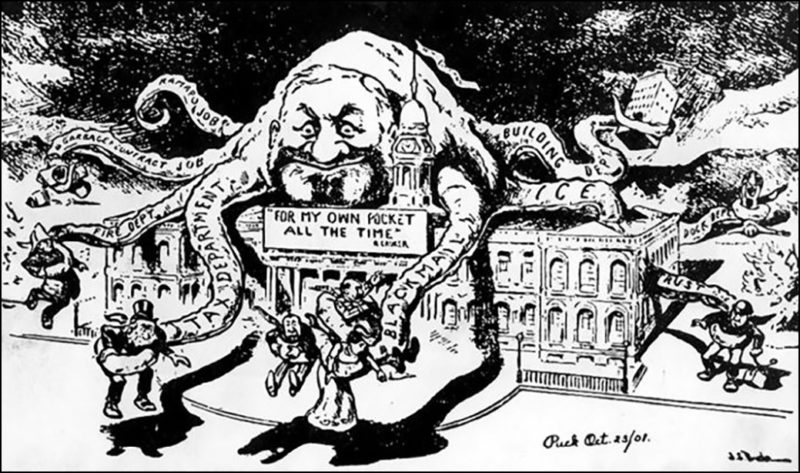

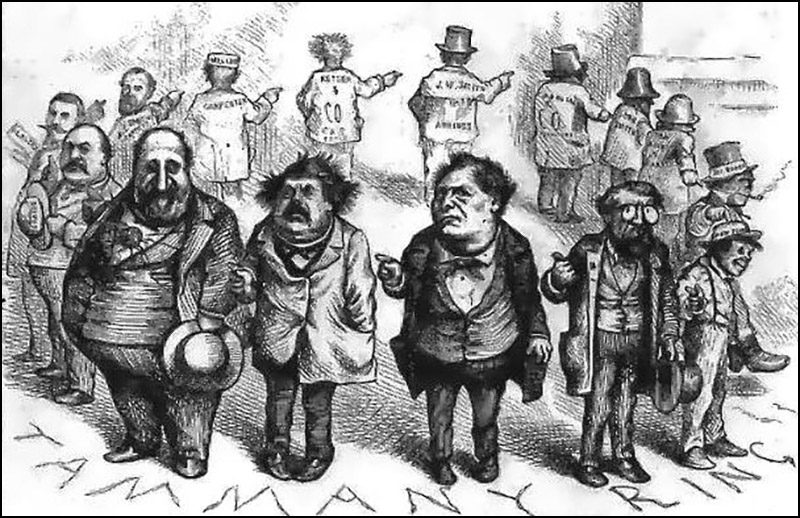

For obvious reasons the names of the persons interviewed are not given, but Mr. Flynt vouches for the literal truthfulness of the interviews. Taken together, they give a full exposition of the system of police protection of vice and crime existing in New York as it is understood by those protected. According to this testimony, the present system rests on what Mr. Flynt aptly calls “The Tammany Commandment”—the great unwritten law that be you gambler or thief, keeper of saloon or disorderly house, you are safe in your miserable trade as long as you pay your monthly tribute to the police.

While Mr. Flynt and his guide “Jim” made very general explorations, this article is mainly the result of investigation in New York’s worst precincts; and it is notable that these worst precincts are located in those parts of the city (the East Side) where the municipality should make the greatest effort to give to the people clean government—if only to teach them by example. Mr. Flynt’s name is a sufficient guarantee of the trustworthiness of the statements he makes. If any other proof than his name were needed, we have it in the revelations recently made in the courts of New York City. – McClure’s Magazine]

“JOIN the Tammany association next door, meet the district leader and the captain, and you can get what you want if you’re ‘right.’ If you ain’t ‘right” you’ll get no protection.”

“JOIN the Tammany association next door, meet the district leader and the captain, and you can get what you want if you’re ‘right.’ If you ain’t ‘right” you’ll get no protection.”

It was a representative of an East Side resort who delivered himself of this sage advice; he was talking to one of the surviving Manhattan Bank robbers and myself. We had approached him in order to make an inspection of the resort, and to see whether we could persuade him to talk with us about the police protection which places such as his must have. The young man was completely off his guard, and told us about the local captain, neighboring dives, what it costs to run them, who f collects the monthly envelopes, and what the envelopes contain. He finished his confession with the statement about the necessity of being “right.” The ex-bank robber—I will call him “Jim” for short—and I thanked him for his generous treatment of us; said “So long,” and departed. While we were walking along the Bowery, Jim was moved to comment on our friend’s advice, and in the course of his remarks he said:

“It’s just as it used to be in my day. You got to be right or you can’t get next to anything. That’s been the Tammany shout ever since I’ve known the organization. They get leary of you if you don’t stand in with them.”

“Were you ever in with them ?” I asked.

“Oh, I used to do certain kinds of work for the Tweed crowd, but after I went on the turf for good I didn’t mix up much with them. A crook has got to look out for himself, and I didn’t trust any gang to take care of me. Even now, although I’ve squared it, I wouldn’t take chances with the police here without having a talk at headquarters first. You see this?” And he handed me the card of a gentleman whose name cannot be mentioned. On the back of it were written these words:

MY DEAR GEORGE: This is a personal friend of mine. If anything should happen, please don’t do anything until you send for me.

“Who’s George ‘” I inquired.

“I don’t know who he is. I forgot to ask, but I guess he must be pretty strong. The party that gave me the card said that some o’ those young fly-cops downtown ‘ud give a piece o’ one o’ their fingers to pick me up and get an advertisement out of it; and he thought the card might help a little in case there was an arrest. None of the youngsters know me, so I ain’t worryin’ much, but if I was going to live here in the city I’d make myself known at the front office.”

“Why would you do that?”

“I told you-so as not to run too many chances. I’d go to the chief, and I’d say: “My name is So-and-so, and I used to be a thief. I squared it a number of years ago, and am living on the level now. I propose to stay in this town, and I mean to earn an honest living. I don’t want to be bothered by any of your young men, and I come and tell you who I am, and what I am doing, so that there won’t be any misunderstanding. If your young men get after me in spite of what I’ve told you, I’ll squeal on every bit of crookedness in the Police Department that I can find. Good day, sir.”

“Do you think it would be good policy to talk that way?”

“Yes, I do. A man who has squared it and paid up his penalties has a right to be left alone. Yet here I am with this card in my pocket for fear that I’ll be picked up on spec. That shows you how ‘right’ the gang is. The thief is made a stall to cover up the protection given to the gamblers and divekeepers.”

“I don’t understand you.”

“Why it’s this way. The police arrest me, for instance. Then they make a big hue and cry about what a desperado I am. The newspapers shove the thing along, and the public is made to believe that the police are attending to business. But how often do you hear of their arresting gamblers and protected unknown thieves?”

“Pretty frequently of late.”

“That’s the work o’ the Committee of Fifteen. The police themselves wouldn’t raise a finger to arrest a protected gambler if the committee didn’t make ’em. Yet they’ll go and arrest “Nibbsy,’ ‘Big Cleveland,’ and those other crooks just for loafin’ around a bank. That’s out-an’-out four-flushing, and the public ought to know it. I tell you what you do. You come with me. We’ll look up some of the old timers, and hear what they have to say about the Tammany shout, ‘Be right.’ You’ll find some that’s squared it, got in the gang and won out. Course they’ll tell you just what that fellow did in that place, but you’ll find some others that won’t.”

The suggestion attracted me, and for the following week we devoted our time to interviewing acquaintances of Jim’s who had left professional criminal “work” in the technical sense-there were a few exceptions—and were either proprietors of “joints” or men who had made so much money out of proprietorship that it was no longer necessary for them to do anything but live on the interest of their accumulated capital. Jim’s main reason in looking them up was to learn whether they had done better than he had.

My interest in the interviews was to hear what gamblers and “joint” keepers have to say concerning what Jim calls “the Tammany shout,” and what I call the Tammany Commandment. Every human being who has reached the years of discretion has made up his mind whether it pays to observe the Ten Commandments. I was anxious to discover whether it pays in New York to observe the Tammany Commandment – “Be right” — and, if it pays, who takes in the heaviest winnings.

The young man whom I have quoted put the Commandment plainly enough for Jim and me, but in order that there may be no doubt in the reader’s mind in regard to its full meaning it seems best to elaborate his statement before reporting the evidence that was gathered. My understanding of the expression “right,” as used in police and criminal circles, is that it stands for conduct exactly the reverse of what the word describes among respectable people. A detective who is “right,” for instance, is a man who takes bribes, closes his eyes when a known criminal passes him in the street, and is himself an unknown or “unmugged” thief. In other words, the expression “Be right.” really means “Be wrong” – go back on society and get all the profit possible out of dishonest dealings.

The young man whom I have quoted put the Commandment plainly enough for Jim and me, but in order that there may be no doubt in the reader’s mind in regard to its full meaning it seems best to elaborate his statement before reporting the evidence that was gathered. My understanding of the expression “right,” as used in police and criminal circles, is that it stands for conduct exactly the reverse of what the word describes among respectable people. A detective who is “right,” for instance, is a man who takes bribes, closes his eyes when a known criminal passes him in the street, and is himself an unknown or “unmugged” thief. In other words, the expression “Be right.” really means “Be wrong” – go back on society and get all the profit possible out of dishonest dealings.

All told, I made the acquaintance through Jim’s introduction of about twenty men who observe the Tammany Commandment either completely or partially. Some of them are men who have always been unknown “grafters”—they have never been arrested, indicted, or imprisoned—but the majority were like Jim, in fact old pals of his-men who have “squared it ’’ as far as being active “guns.” is concerned, and are to-day making money out of their pull with the Powers that Rule. It is my opinion that every one of the ex-criminals whom we met is prepared to do “fence” work—buy stolen property-for thieves who can be trusted, but this is not the way most of them make a living.

Their principal business is running saloons, disorderly houses, and gambling places. The majority of the worst dives in New York are in the hands of men who have either been in prison as convicts, or have at some time in their career been professional pickpockets and burglars. They are all observing the Tammany Commandment in some measure, and the police and others are receiving money from them for protection.

Two of the most interesting ex-thieves visited were men who declare that being “right” is so much more profitable than professional thieving that, if they saw comparatively safe money lying at their feet, they would kick it away rather than risk their present opportunities in an arrest. One of them is an old river-thief and pickpocket with whom Jim used to work twenty years ago. He is intimate, he declares, with one of the most important Powers that Rule in the city; indeed, he goes so far as to say that the two once ran a “joint ’’ together. This statement has been contradicted by other informants, but the fact that the important Power referred to got the exriver-thief’s brother out of prison, where he had been sent for life, is circumstantial evidence that there is considerable friendliness between the two. It is worth a journey to San Francisco to hear the old man wax eloquent over the “graft’’ that comes from being “right.”

“Why, Jim,” he said, turning to my companion, his face beaming with delight, “I wouldn’t go back to the old graft again for $10,000—I wouldn’t, Jim. When I came home (returned from prison) I went to shoemaking first. After a while I got acquainted with his Job-lots, and he helped me fix up a place in – Street. He was just starting out as a politician then, and he got it into his head that he’d fight the police. They’d made him mad for some reason or other, and he came to me and said: ‘-, when the wardman comes around for his envelope the next time, tell him to go to the devil.” When the wardman came I didn’t like to say that, so the first month I just says: “Business is poor, and I can’t afford the envelope this time.” He took the con and went away. The next time he came I told him the truth. Then there was the devil to pay with the captain, and eventually I had to close up. But I opened up again in – Street, and now I’m here, and, Jim, things are going as fine as silk. No more stealing in mine, Jim.”

A tipsy sailor had been standing at the bar while these remarks were being made, and as he turned to go out the door a dollar bill fell from his hand or pocket. The old river-thief noticed it first, but the pardoned brother got it. No attempt was made to reconcile this performance with the proprietor’s alleged hatred of theft. Pretty soon a bell rang. We all sat silent for a moment, and then the proprietor turned to his brother and said: “That’s that party upstairs hitting the pipe. See what she wants.’’

Jim and I got up to go.

“Well, so long, Jim,” said the proprietor; “ain’t I right that we were crazy when we used to steal?”

‘‘Sure.’’

The other ex-criminal is a man who claims that he is the only one of Jim’s old crowd who has never done time. He declares that he “squared it” in the neighborhood of seventeen years ago. Jim sold him about eight years ago a “swag” of jewelry stolen in England. As in the former case, no attempt was made to make this fact tally with the man’s statement as to the time when he gave up criminal practices. He is the owner of considerable real estate in Greater New York, and the proprietor of a successful hotel. So far as I can judge, he is “right” principally with the more important Powers that Rule. A story that he told makes me think this. He was playing cards with his sister-in-law one evening when a man who said that he was the wardman was announced.

“Well, what if you are the wardman?” the hotel proprietor queried.

“Of course you know who the wardman is?”

“Yes, I do, and you get out of that door as fast as you can go.”

The wardman lingered.

“I chucked him out as if he was a piece of wood,” Jim’s friend remarked. “I can be right, Jim, and I am, but when a dirty little wardman mixes in a family game o’ cards I kick, I do.”

“Do you remember that time you, I, and that other fellow got a pocketbook on that Fourth Avenue car ?” Jim asked.

The man smiled at first, and for a second the remembrance seemed to entertain him, but it was only for a second.

“Say, Jim, what fools we were, eh?” he said. “Think o’ the chances we took in those days! Why, do you know, I wouldn’t risk as much for $150,000 to-day as I did then for $50. I tell you life’s become pretty sweet to me. I don’t want any prison in mine. I’ve done well since I squared it, and I mean to stay squared.”

The third man interviewed is “right” or not as it suits his purposes. He does not accept the Commandment as a law. He is still a thief-at least he means to “work ’’ in the neighborhood of Buffalo this year and has a good deal of the thief’s distrust of the Powers that Rule. He is still rated one of the best pickpockets in the United States. I heard him say that in his younger days, when Jim and he used to chum together, the Seventh Avenue street car horses actually used to wag their ears when they caught sight of him, so well did they know his “graft.” We found him sitting by a window in a Bowery hotel.

After greeting us he turned his face to the street again and said: “I’m looking for a fellow. A half-hour ago the funniest thing happened to me that I’ve ever heard of. I was standing at the corner of Broome Street and the Bowery when one of them Sheeney pickpockets took my whole front (watch and chain) before I could so much as say “Stop.”

I gaped after him like a sixteen-year-old girl. I’m looking for him in order to tell him that if he is prepared to take such chances regularly I can get him a barrel o’ money. Think of it, will you, Jim, in broad daylight, and the “Jerseyman’ the sucker. Course I couldn’t make any holler, ’cause I’m too much of a thief myself, but never in my life have I seen such gall.”

Jim and he then exchanged autobiographies for the last twenty years, both romancing a little, but in the main sticking to facts. Finally the “Jerseyman” told us of the different places he had had in the Bowery.

“I’ve had five all told. I got rid o’ the last one a short time ago. The breweries and some other people are looking this time for a fellow by the name of Kirby. When they find me we’ll all probably be a great deal older.”

“Did you stand for protection?” Jim asked.

“When I had to I did, but you know me. Why, Jim, this town is so crooked that even the uniformed policemen would shake me down if they thought I had any money on me. Yes, sir, the flatty (policeman) right on this beat would stick me up and make me cough if he could meet me up an alley in the dark. I’m getting sick of coughing and trying to be right. I ain’t going to be right any longer unless it’s a case of going to prison. To the devil with everybody but myself is my religion now.”

The “Jerseyman” is reported to have saved about $15,000 during a criminal career extending over twenty five years. Most of it came from thefts rather than through obedience to the Powers that Rule.

Another grumbler in connection with the Commandment is the keeper of a resort in Harlem. He would prefer not to be “right,” because he has no love for the police or the politicians, but his business requires him to pretend to be so. He gave us some interesting information in regard to how the monthly envelope which he hands the police is collected.

“You see I sell liquor without a license,” he explained, “and I wanted the thing arranged so that the envelope was going to protect me downtown in the Front Office as well as up here.”

“Do you have to fix both places?”

“It’s this way. If I only fix the local people here some Front Office fly-cop might walk in and ask for his graft, too. So I asked the party that arranged the thing to cover me in both places.”

“Who collects the money?”

“Oh, he’s an old guy that’s a sort o’ pet of one of the big fellows downtown.”

“How much do you give him?”

“Twenty-five a month.”

“When does he collect?”

“Usually on the second or third.”

“And you’re never disturbed?”

“Once in a while a flatty in citizen’s clothes comes in and tries to look wise, but I tell him that I know my business, and he’d better leave me alone. I keep open as late as I like. You see, having no license, I’m not down on the list o’ places that have to close at a certain time; and while all these other places up here have had to shut down after a certain hour, I’ve kept things running as long as there was any money to make. Even if they should bother me I can make it hot for them if I want to. One day a fellow—a reporter, I guess he was—came to me and offered me for $20 an old indictment against me. I grab the papers, and tell him that he can whistle for his money. A few days later a copper comes to me and wants to know why I didn’t pay the reporter what he asked. ‘That’s none o’ your business,” I says. Well, if the police ever try to dig into me again the way they did some years ago I’ll flash those papers right in court and tell what I know about them.”

“How do you think the reporter got hold of them?”

“Some clerk stole ’em, I think, and told the reporter to get what he could for ‘em. I’ve got ‘em now and they’re locked up tight, too. I ain’t looking for any trouble, and the coppers are welcome to the twenty-five per; but they got to be right if the want me to be.”

There was considerable difference of opinion among the men interviewed as to whom one should be “right” with. Some thought that the politicians were the main persons to go to for assistance, while others advised having nothing to do with them. The owner of several disorderly houses on the East Side was of the latter opinion.

“Don’t go near the politicians,” he remarked. “As a rule they only tole you along, and your money goes for nothing. I tackle the police direct, and they always give me my money’s worth.”

“What do they tax you apiece for your different joints?”

“Fifty dollars a month, but that guarantees me absolute protection.”

“How can the police protect you if the Committee of Fifteen, for instance, wants to raid one of your places!”

“The Captain sends orders when to close down or open up, and I act by the orders.”

“But suppose the orders don’t come in time to prevent the raid?”

“That hasn’t happened yet, and I’m not worrying anyhow. I know my business. I’ve got ways of my own of finding out things.”

“You don’t mean to say that you can tell when one of your places is going to be pulled?”

“I can’t always be sure, no; but my men are careful to keep a good look-out, and they generally see what’s doing.”

A near neighbor of this man, the “manager” of a “hotel,” also declares that it pays best to deal with the police direct, but he has very little respect for the Republican captains.

“They’re the worst cops in New York,” he said. “I don’t mean that they won’t be right, but what they’re willing to do and take shows that it’s graft that they’re after. Take the captain in this district. Republican. Could I run this place any stronger than I do now? Not a bit. He stands for practically everything, and there ain’t a slimier precinct in the city.”

Although the testimony of both these men is expert, there is equally good testimony from quite as experienced observers that at least one politician in the city is a very useful man to know. I heard of at least ten men whom he has succeeded in releasing from prison, and I met several whom he knew how to keep from going there. Who he is and where his power comes from are matters that he understands better than I do, but whether his name is John Doe or Richard Roe, there is no doubt about his being “right” with all those who are “right” with him.

One of the most successful gamblers in New York—an old acquaintance of Jim’shas a similar reputation; so far as Jim knows he has never squealed on anybody, and he is the “bodyguard” of all the old timers who are good for anything and are prepared to obey the Commandment. “He, George Howard, Billy Porter, and I,” Jim told me when speaking about him, “robbed a bank together in this town about eighteen years ago. We bulged out so with the silver and other stuff we had on us that we took up nearly the whole side of a car—just the four of us.”

”Do you think he has really “squared it?”

“That fellow who gave me the card to George said he’d give me one to this fellow, too, if I wanted it, and that he’d probably give me a job as a steerer for some of the gambling places. A man who can give another man a job as a steerer for cribs can’t be said to have squared it, in my opinion.”

“But how does he remain so successful then?”

“Squaring it doesn’t mean simply quitting stealing. It means living on the level in every respect. This fellow ain’t on the level in that way, and he knows he ain’t. He’s successful, as I told you, because he’s square with the gang-he’s right. If I was a thief still I’d look him up to-night.”

There has been a great deal of discussion of late with regard to the profits of the professional gamblers in New York. The only light I can throw on this topic is that every old gambler that Jim knew and made inquiries about, except one, seemed to be in comfortable circumstances.

One said that the daily expenses for the most modest of his different pool-rooms were $80. He said also that he got very distinct orders when to close his places.

In the upper part of the city there is a man who is rated “right,” and yet does not pay a cent of protection money for the privilege of keeping his “hotel” open after hours. Jim unearthed him, and thinks that he knows the secret of the man’s immunity from the police tax.

“He’s what you call a good fellow,” he explained. “He spends his money freely, hob-nobs with the police, and is a big lusher. He’s also a bit strong about election time.”

“Hob-nobbing with the police, if it costs money, is merely another way of “giving up ’ to them,” I replied.

“If you want to look at it in that way perhaps it’s so, but the idea is that the man don’t hand out any envelope; he ain’t taxed, See?”

The bulkiest envelope that I know about is reported to contain $125. It is said to come from a place licensed as a hotel. Doubtless there are larger contributions than this one, but $25 and $50 envelopes seem to be in the majority. The envelopes go almost invariably to the police, and I consequently place them first in the list of those who “win out ’’ obeying the Tammany Commandment. There are a few very successful politicians who have arrived at greater prominence and taken in more financial “scale ” than any individual member of the police department; but, numerically speaking, the police seem to me to take first honors in the race for the money which belongs to those who understand how to be “right.”

Take, for example, a certain detective who receives $1,300 salary a year. Some friends of mine spent several nights in his company a year or so ago, and he insisted on paying practically all the expenses of the “outing.” His reason for doing this, if I am correctly informed, was that he desired to show my friends, who were from the provinces, that his “graft’’ was so immense that he could afford to settle all bills that were presented. Indeed, he made a point of assuring my friends that they had no such “graft” as his, and consequently why should they spend their money? The time comes in the life of such a man when his “graftings,” or rather discreet advertising of their size, pleases him as much as the hard earnings of honest toil delight the struggling laborer; and he loses no opportunity to notify fellow “grafters,” or what he takes to be such, how well he is doing.

The gamblers come next to the police, I think, in making money out of being “right.” Until comparatively recently they have been very numerous in New York, and there is no doubt that their “graft ’’ has been large. Just at present they are keeping rather quiet, but the probability is that they will show their hand again in no unmistakable manner before many weeks are passed. They not only make a great deal of money themselves, but they help the police to make money also, and companions of this character are hard to keep down.

Next to the gamblers comes the army of dive-keepers. As in the case of the gamblers, these people are not doing as well now as they did before the reformers got after them, but they are natural winners at all times when the Commandment can be openly obeyed. I have heard a number of them complain recently about the bad business that was being done, and some have articulately wondered whether it was not an opportune moment to get out of “the trade”; but the majority mean to hang on until “right” times return again.

Concerning the “right” politicians and their success there is not much that I can say, but I believe they come last, as far as numbers are concerned, in the list in question. I think, for instance, that little of the money which the police collect, and which is popularly supposed to find its way into the pocketbooks of the “big guys,” ever reaches these pocketbooks, except that which an inner clique of the most powerful ones receivesfrom gambling houses and pool-rooms. The amounts collected from this source in certain precincts are too great and too readily ascertained to be absorbed by any captain whose assignment to a particular post is under the control of a superior officer. And, again, that superior must meet thedemands of those who have placed him and hold him where he is. The old-time gambler in New York, according to tradition, may have “squared ” himself with the organization by means of his yearly campaign contributions, and thus settled with the captain on such terms as he could make; but that was before the gambling business of the town had been systematized and syndicated.

Jim pointed out to me in the street an old politician of the Tammany school to whom he (Jim) twenty-five years ago used to lend coats and vests in order that the man might appear in the court-room as a decently clad “rising young lawyer.” To-day the politician rides in his carriage and Jim takes the trolley. Whether the politician got his carriage by being “right ’’ or not he alone can tell. I saw him shake hands with Jim, heard him say “Hello! ” in a pleasant voice, and then watched him pick his way like a cripple into a hotel. He refused to take a drink with Jim, which I thought rather snobbish. He has his “coach and pair,” and Jim has good health. Nearly all of the other oldtimers, Jim’s former companions, also have good health, and, as I have shown, some of them have accumulated money. With all respect to Jim’s opinion, I think that the majority of those who have “squared it ’’ are glad to obey the Commandment.

On the other hand, I am convinced that Jim is right about the man who has not “squared it” — the professional thief—being made a “stall” by the police to deceive the public in regard to the protection given to gamblers and the like. Not that the thief does not receive any protection—he is protected to a certain extent in every large city in the United States; but when it suits the purposes of the police to make what is called a “grand-stand play,” the thief rather than the gambler and the dive-keeper is the person selected to be exposed.

Before leaving town Jim had a final talk with me, and I asked him point blank whether what we had seen and heard convinced him that it paid an old-timer to be “right.” He replied as follows:

“If I were going into the saloon or gambling business I’d join the gang, but otherwise I’d never go near it. It wouldn’t pay me as an old-timer to be right, ’cause I don’t want any odds from anybody. I’ve squared it out and out, and I’d only get crooked if I mixed up with the gang. The town is so open that a fellow can’t be on the level and right too. As far as I can see it’s a worse town than when I used to live here and help make it bad; that was in Tweed’s time.’’

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

By subscribing, you will automatically receive the latest episodes downloaded to your computer or portable device. Select your preferred subscription method above.

To subscribe via a different application: Go to your favorite podcast application or news reader and enter this URL: https://clearwaterpress.com/byline/feed/podcast/