The Caliph and His Court

Episode 18•

The Caliph and His Court

• Now and again in the regular round of delinquencies there comes the unmasking of a tragedy.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Email | TuneIn | RSS

SHOW NOTES ____________

The Caliph and His Court

By Arthur Ruhl

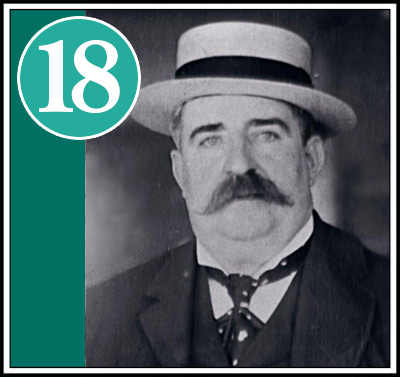

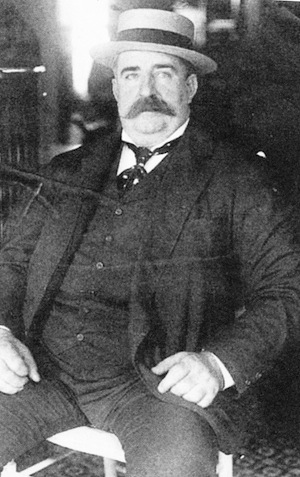

[“William S. Devery, the Caliph of Mr. Ruhl’s sketch, entered the New York Police Department in 1878, when he was twenty-three years old. In 1881, he was made Roundsman; in 1883, Sergeant; in 1891, Captain. In 1893, he was tried, at the instigation of the Parkhurst Society, for failing to suppress disorderly houses, and was acquitted. In 1894, he was tried for accepting a bribe from a contractor, and was dismissed from the department. He did not appear at the trial, but sent word that he was too ill to attend. A police surgeon examined him and confirmed the statement. No other doctor was allowed to cross the threshold. The Supreme Court decided, however, that he had not received a legal hearing and reinstated him in 1895. In 1898, Devery was made Chief of Police. In his own words, he has been “accused of every offense on the calendar, excepting being off post.” Periodically the newspapers have talked of his removal, and a recent police law did legislate him out of office. Commissioner Murphy immediately appointed him his Deputy, and in this position Devery is still the acting head of the force, and is known everywhere as the “Big Chief.” – McClure’s Magazine]

THE room was not unlike the traditional district school. There were the same rough board floor, the bare white walls, the transverse wooden benches, and the tall windows with their thin scholastic panes. But no barefoot boys were whittling entwined initials and bleeding hearts, nor were there peach-blow maids in pigtails and pinafores to inspire pastoral idyls or moral verse. The wooden benches creaked beneath the weight of some threescore ponderous beings in blue and brass buttons, each one of whom, by token of his calling, was steeped in sophisticated knowledge of the sodden I side of the life of the town. Behind the desk—the horseshoe-shaped desk that has heard so many dark tales in its day—sat, instead of a rural Ichabod or a gingham aproned school-ma’am, an individual with the face of a retired pugilist, who held in his hand, in a way no mere pedagogue ever held, the fate and fortune of every man in the room. This room was the trial room at Police Headquarters. The men in blue and brass buttons were naughty New York policemen upon trial. And the man behind the horseshoe desk was the “Big Chief “—known just now in the quaintness of official language as Deputy Commissioner Devery.

It is the fashion in some quarters to regard the men in blue and brass buttons with unbending solemnity and extreme distrust. The easy moralist, vaguely aware of the existence of that machine whose sign is the tiger, sees black-and-yellow stripes streaking every uniform and thinks not at all of the husky young chap inside who has troubles of his own. The Circean caricaturist, compelled to treat the Big Chief with equal acerbity, draws him through all the gamut of transmigratory punishment from that of the scaly serpent to the rabid bulldog, and fails to suggest that he is yet a flesh-and-blood ruffian with the humors belonging to a man of Hibernian descent and a weight of some twenty stone. We shall take another point of view—forgetting the things which so keenly interest parsons and politicians. In the phrase which the Big Chief always uses when he gets a question he doesn’t want to answer: “I’ve got nothin’ to say touchin’ on or appertainin’ to them matters.”

The men, whose bronzed faces and convex chests presented a phalanx in front of the horseshoe desk, had come from the various precincts all the way from Tottenville to High Bridge, as they come on every Thursday morning in the year, to bluff, to laugh, or even frankly to explain themselves out of all sorts of charges, from that of wandering a couple of blocks “off post” to that of breaking some servant-girl’s heart. They had learned their stories and coached their witnesses, and now they waited, chuckling hoarsely and whispering ponderous ‘jests, while the Caliph looked over the list of complaints.

The younger patrolmen, and those from the farther precincts, who stared steadily at the Big Chief, saw a big man with a bull-neck, with a policeman’s mustache, and hair that once was black and now is frosted with gray, with curious bluish gray eyes that now have the drollest quirk of merriment in their corners, and again stiffen and gleam until they seem to pierce the very uniform of the trembling patrolman who tries to stand before them.

At such times the blood leaps into the Caliph’s face, until you think of red flame showing through smoke.

In a sputter of words, faster than an auctioneer’s sing-song, the old clerk read: “Officer – Michael – Murphy – Ninety – ninth – precinc’ – off – post – an’-found-in-liquor-storeon-night-of,” etc., etc.

Out from the blue-coated phalanx, preceded by his roundsman who had caught him “off post,” and who made the complaint against him, the delinquent patrolman marched to the bar.

“Complaint correct as read, Rounds’?” asked the Caliph, and the roundsman solemnly nodded his head. It was a great moment for the roundsman. Basking in conscious rectitude, erect, austere, with chin in, weight resting on one leg, and his hands crossed on his stomach, he awaited, with a fine Olympian tolerance, the progress of the case. The Caliph turned his eyes on the patrolman—a look that took in every detail from the state of his complexion and his uniform to the man’s ability to tell the truth.

“What you got to say, officer?” he put bluntly.

“On the night in question,” began the patrolman, with the air of one about to demonstrate a proposition in advanced geometry, “I was tryin’ doors along me post when I was suddenly took with cramps. I——”

“Look a-here, young man! How long ‘a’ you been in the business? Three months, eh? An’ you’re a-havin’ cramps already! You’re a quick. learner, you are. Where ‘ud you a-been in case of a murder or fire or burglary or anything requirin’ quick action touchin’ on a casuality? I’ll fine you ten days’ pay. You stay on post!”

As the young patrolman scuttled out of the trial-room the Caliph rumbled out: “It’s only you young men what won’t do your duty. I don’t see none of the old men here. I’m not your rounds’, but I can’t go up the street without a-seein’ you talkin’ to each other or to some o’ the young ladies on your post. You won’t walk the sidewalk at all. I’ve seen the day when, with fly cops an’ all around, I couldn’t a-leaned around the corner of a bay window without gettin’ a complaint.”

The “cramps excuse” which the young patrolman ventured to use is one of the several traditional pleas which have been handed down through generations of “off post” policemen like precious amulets. The “man on the sidewalk” lacks the creative imagination. He must be started with a plot. In descriptive imagination, in the convincing laying-on of local color, he comes out strong, and once possessed of the cramps motif, or one of the few others in his repertoire, he laboriously proceeds, solemnly certain that he is secure.

Genius springs triumphant, however, from the most unfallow ground. There was once a patrolman—

“Why, it was just this way, Mr. Commissioner,” said he. “On the mornin’ in question, at about twenty-seven minutes to three o’clock I heard a citizen shoutin ”Fire! Fire!’ about two blocks off me post. I ran to the spot thinkin’ to turn in the alarm or assist in wakin’ the tenants in the house, when I found a milkman callin’ out for to wake a customer on the third floor of a flat-house. That customer’s name was ‘Myer,’ an’ the milkman was yellin’ ‘Myer! Myer!’ I was just after hearin’ this when me roundsman rapped for me.”

The complaint was dismissed. This was before Devery became a trial judge, and the man who thus rewarded a patrolman’s skill as a raconteur now presides over a more august and less diverting body—the United States Senate.

Presently the clerk read a complaint which stated that So-and-so was found several blocks ” off post” in a dazed condition, ” unfit to perform police duty, and standing in front of a cigar store.” The patrolman had had a fresh shave, and he seemed to be feeling pretty fit, and so, instead of giving the stock story about having been seized with chills and having taken quinine and whisky with untoward results, he tried to bluff it through—spoke darkly of a mysterious vertigo and the presages of his physician, and of a couple of suspicious persons whom he thought best to watch from the shadow of a cigar-store door.

The Big Chief’s gray eyes, peering out above his puffy cheeks, saw everything, but he chose, for a moment, to dally with his prey.

“Um,” he murmured deeply, “why didn’t you get your side partner to cover for you? All you had to do was to jing your stick on the sidewalk or give the double rap.” Then all at once his mildness left, the flame came into his face, and his eyes grew hard as they flashed out toward the man who stood with quaking knees and hands rubbing nervously one over the other.

“Stand up!” he roared. “Stand up and have some nerve about you! What do you come down here an’ lie to me for? You ought a-hire out as a cigar-store Indian. I know you, an’ I know what you’re a-doin’. You’re a-bendin’ your elbow too much. D’you hear that? You stop bendin’ your elbow!” And then he rapped on the fine.

In Devery’s vivid vocabulary “bendin’ the elbow” means “drinking”—the elbow being bent to convey to its owner’s mouth the cup that does more than cheer. The trick of suddenly turning on the men who come before him with some piercing accusation, which his intuition or his knowledge of every crook and corner of the “business” gives, is one of his strongest weapons. I have seen him order a young patrolman to show his profile, and thereby identify him as the leader of a gang of boys that he had run up against in the old days when he, too, was “on the sidewalk.”

Once I heard him flatly blurt out: “Where’s your moustache?”

“I shaved it off—for the summer,” stammered the policeman, looking as though he saw a ghost.

“Um—I see—I see. Gettin’ too warm for you, eh?” And then Devery showed that he knew perfectly in what sense it was getting too warm for the man. For very good reasons that policeman was trying to hide his identity. It seems sometimes, indeed, as though the Caliph knew the inside history of every bluecoat from the Battery to the Bronx.

The Caliph stared glumly at his list of charges while the clerk read off the complaint of a citizen who averred that without provocation he had been pelted with blasphemous language and brutally clubbed. It wasn’t the sort of thing that interested the Caliph. He regards citizens who complain of being clubbed with about the same enthusiasm that the school-ma’am aforementioned regards the sort of parents who always make a row when their children get spanked. What the newspapers and the “better element” call brutality, and what, in all truth, is brutality, the Caliph sees as only that necessary firmness without which any sort of policing force, from an army of occupation to a boarding-school proctor, must lose its prestige.

“Why didn’t you lock this man up ?” demanded the Caliph, when both stories had been told. “There’s just one thing for a police officer to do touchin’ on a case like this. If a citizen does anything wrong, why, you can lock him up for violatin’ a law or for interferin’ with a police officer in the performance of his duty. If he don’t do nothing wrong, why, you ain’t got no right to club him. I’ll fine you five days for not lockin’ this man up.” The patrolman departed with a furtive grin working behind his mouth, and the citizen, flushed and disconcerted, walked slowly from the desk trying to decide whether or not he had got the best of it.

The Caliph showed again his hatred of weakness in the performance of police work when a patrolman came up charged with having let his prisoner escape him. The man told feelingly of a fierce fight in a dark alleyway and showed the scar on his temple from the thug’s black-jack.

“I drew me gun an’ fired in the air to show that I meant business, but the man kept on runnin’ an’ escaped.”

The Caliph grunted. “Twenty days’ pay for not hittin’ him. Next time you hit him.”

Then the clerk read something about being caught skylarking, and two human mastodons marched into the hollow of the horseshoe desk. They were Broadway cops, their deity showing, like Venus’s, in their gait, and the word skylark seemed almost blasphemy. Moreover, one of them had a black eye.

“What you got to say, Donnelly?” asked the Caliph.

“Well, Chief, it was just this way. There was two dogs a-fightin’ at the corner of Canal Street an’ Broadway. A large crowd of citizens gathered about the scene, creatin’ disturbance an’ interruptin’ traffic. I was after separatin’ the dogs, whin Klonberg comes along an’ touches me up in the seat of me pants with his stick. I turns around naturally, bein’ interfered with in the performance of me duty, an’ as me arm comes back me elbow hits his eye.” As a matter of record, both men had been on the sick list for eight days following this playful rencontre, and a concourse of citizens had watched the fight with all the awesome delight with which a party of Mound Builders might have viewed the struggle between a couple of prehistoric pachyderms.

“Did you touch Donnelly up ?” demanded the Caliph.

“I did, sir,” replied the Human Mountain.

“Uh!” grunted the Caliph, the most curious quirk imaginable creeping into the corners of his eyes. “If he was the Donnelly of old an’ you’d a-tried that, he’d a-put both your eyes on top of your nose. I’ll fine you ten days’ pay. An’ you, Donnelly, I’ll fine you ten days’, too, for lettin’ him touch you up without you a-blackin’ both his eyes.”

When the more serious cases come, the man Devery breaks through the thin veil of judgeship, of Deputy-Commissionership, or what not, just as surely as in these playful ones, but with the fun all left out. Blind as he maybe when once the flame has got into his face, it does not come easy to the man to hit a blow in cold blood. When a heavy fine is to be rapped on, the Caliph behaves somewhat after the manner of a certain kind of fireworks — the sort which burns and burns, seemingly feeding its fierceness with its own sparks until all at once it goes off with a bang.

In the case of the Caliph the bang is the thirty days’ fine—or worse. I have seen a shifty lawyer, whose years of checkered service in the Headquarters’ courtroom had taught him that something more human than the law of the books wins a case before the “Big Chief,” goad him with the name of a man who had nothing whatever to do with the matter in hand, but whose work at that moment was making the police the laughing-stock of the town, until the tide of the Caliph’s passion swept his reason clean away.

A patrolman had so abused his wife and children that he had been thrown into jail for three months, and now he had come before the departmental judge. Everything about the case seemed to stir the Caliph’s prejudice against the man in blue. That he would be “broke” seemed sure, when the lawyer mentioned the name of a certain justice who had given the policeman his civil sentence and who, as it happened, was then almost daily raiding gambling places under the noses of police captains who swore that gambling didn’t exist.

The first mention of the name made the Big Chief start in his chair as though stung with a picador’s dart. For half an hour that lawyer “sparred for wind,” and with every half-dozen sentences, with all the insinuation of the “honorable men” in Antony’s speech, he flaunted the hated name before Devery’s face as he might flaunt a rag before a bull.

And at last the baiting succeeded. The Caliph surged up in his swivel chair. He forgot the case before him, forgot that his was the name signed at the bottom of the complaint-papers, and he told the patrolman to go.

“There’s a lot of little tin soldiers with guns on their shoulders shootin’ ’em off in the streets an’ raisin’ riot an’ rebellion an’ degradin’ the positions they hold. Complaint’s dismissed! Judge Jerome ain’t goin’ to run New York!” And the whole roomful of sympathizing men did what had scarcely ever been done in that room before—broke into headlong applause.

Devery is perhaps most diverting when, less the Big Chief and more the Caliph, he comments on cases which lead him from the departmental path into the broader fields of manners and men. I don’t happen to recall any one phrase, of the many spoken and written at a time when “vice,” as it is somewhat technically known in New York, was receiving its periodical airing, that went nearer to the mark than one of the Caliph’s. A young man, gentle-mannered, who spoke without his “fa,” complained of a patrolman who had refused to arrest a woman of the streets whom the young man said was bothering him. The Caliph listened attentively to the complainant, the patrolman, and the witnesses. Then he turned to the young man.

“An’ so,” said he, “you were disappointed. You were out for a good time that night an’ you didn’t get it, an’ so you thought you’d take it out on a cop. If you’d a-wanted to you could a-got away from that girl, an’ you know it. It takes two to solicit, a lady an’ a gentleman”—the Caliph’s glance went clear through the mild young man as he spoke this sentence—” an’ that lady wouldn’t a-solicited you unless you’d a-made those goo-goo eyes.”

The complaint was dismissed.

Now and again in the regular round of delinquencies there comes the unmasking of a tragedy—no less a tragedy because of the grotesque puppets and the furniture with which the scene is set—wherein some unwilling bluecoat lifts the curtain and gives a glimpse of one of those heart-wrenchings which, so very real to that Other Half, must ever be, for the most of us, unfelt and unseen.

It may be anything from the case of some Yiddish push-cart peddler, whose precious beard has been pulled out by a gang of “muckers” before the very eyes of a patrolman, who has laughed, “To hell wit’ the Jews !” to that of a young girl who has been playfully treated by a man in brass buttons because it was her fate to live in a part of town where the manners of some young women are free.

A young Yiddish woman once came up to the Caliph’s bar. She was scarcely more than a girl, but the black of her dress was mourning for the husband who had died within the year, and she had come to beg that the Caliph would protect her from the hulk in blue and brass buttons, who reviled her and dragged her off to a station-house cell every time he met her in the street. With quick, shivering glances from the patrolman’s face to the Caliph’s, she told her story, gesturing vehemently and hurrying along in the sputtering throaty accent of her race. The big patrolman had courted her as soon as he was put on his post in the Ghetto. Even while her husband was alive he had come to the house—and her family had known it. The husband didn’t count for much at his best, and toward the end he was stricken with quick consumption beyond relief. It had been understood all round that so soon as he was mercifully taken away the big patrolman was to assume his place. And against that time the young woman, proud above her grief that the Irish policeman should deign to notice one of her race, gave him her trust, her homage, and every cent she earned.

A young Yiddish woman once came up to the Caliph’s bar. She was scarcely more than a girl, but the black of her dress was mourning for the husband who had died within the year, and she had come to beg that the Caliph would protect her from the hulk in blue and brass buttons, who reviled her and dragged her off to a station-house cell every time he met her in the street. With quick, shivering glances from the patrolman’s face to the Caliph’s, she told her story, gesturing vehemently and hurrying along in the sputtering throaty accent of her race. The big patrolman had courted her as soon as he was put on his post in the Ghetto. Even while her husband was alive he had come to the house—and her family had known it. The husband didn’t count for much at his best, and toward the end he was stricken with quick consumption beyond relief. It had been understood all round that so soon as he was mercifully taken away the big patrolman was to assume his place. And against that time the young woman, proud above her grief that the Irish policeman should deign to notice one of her race, gave him her trust, her homage, and every cent she earned.

The Caliph leaned forward on the desk, beckoning the young woman nearer, and for a time they talked low together.

“Yes, everything,” the young woman whispered, drooping her head and almost closing her eyes, and as the two spoke together little rivulets of sweat rolled down the patrolman’s face, and you could hear the crick-crack of his finger-joints as, one by one, he pulled them in and out behind his back.

“Here are the letters he wrote me, and the picture he gave me,” and she put a cluttered little packet into the Caliph’s hand; “the letters asking me to meet him on his off-days. And then—after—he was different. And when I went out to see him, he told me to go along. And when I tried just to get my watch and my rings back, he pushed me by the shoulder—like this — and arrested me and locked me up in the station house.”

She glanced shiveringly at the patrolman and huddled closer to the Caliph’s desk, and as she started to speak her voice quivered with fear and appeal. “And now I want you to protect me from that man. Three times he has arrested me and locked me in jail, and when the judge discharges me he locks me up again. He follows me everywhere, Mr. Judge, and slaps my face and calls me names and arrests me, and I dare not go into the street for fear of that man!”

The big Caliph rolled back in his chair, low, volcanic rumblings sounding from within his chest. Then he turned to the patrolman, who, still cracking his finger-joints, could only say that the woman lied.

“An’ so,” said the Caliph, no longer the promoted policeman, but the sophisticated Caliph, cynical yet chivalrous withal. “An’ so you got tired of her. You had your fun an’ you went your distance—an’ you got tired. She gave you everything, even every cent she earned, an’ when you got all you could get you threw her down. She comes out on your post to get her things back— comes out on the sidewalk to bother you a little to get a little of what you’ve took off her, an’ you club her an’ throw her into a cell. I’ll settle your case. I’ll recommend that you be broke.”

“Broke” that patrolman was, and those who saw the Caliph that day knew then, if they did not know before, that chivalry is not monopolized by the Launcelots and the easy sonneteers, and that the Big Chief has another side from that shown in the caricatures.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

By subscribing, you will automatically receive the latest episodes downloaded to your computer or portable device. Select your preferred subscription method above.

To subscribe via a different application: Go to your favorite podcast application or news reader and enter this URL: https://clearwaterpress.com/byline/feed/podcast/