Getting Captain Cameron

Episode 3 •

Getting Captain Cameron

• Ever since the opening of hostilities, the authorities at Washington had sought to effect his capture; but a year of the war had passed, and he was still spreading terror along the Potomac. Listen now:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Email | TuneIn | RSS

SHOW NOTES

Getting Captain Cameron

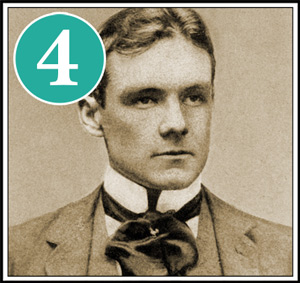

By Ray Stannard Baker

McClure’s, January 1900

An Adventure of Major J.S. Baker of the Secret Service

The following story was told to me by my father, Major J. Stannard Baker, who himself served in the Federal Secret Service Bureau during the Civil War. I repeat it here in substantially his own words. The names, in several instances, are fictitious; but the incidents related are true in every particular.

In the spring of 1862 I was comparatively new in the work of the Secret Service. I had joined the force at the request of my cousin. Colonel L. C. Baker, the organizer and chief of the Bureau, and he was anxious that I become at once familiar with its workings. Perhaps that is why he soon sent me out with Traill for a tutor. Traill was a close-knit, swarthy-faced Virginian, with thin lips and a sharp nose of singularly delicate cut. On his left cheek there was a puckered white spot the size of a flattened minie ball. Under excitement it sometimes twitched slightly and reddened—the only evidence of emotion that I ever knew him to show. Traill had made a reputation in the service. If there was a particularly desperate undertaking in hand, the Colonel had a way of calling off his force on his fingers, man by man, as if he felt uncertain which to send—and then always sending Traill. He knew every by-path and ford and ravine in the Potomac valley, and he possessed an aptitude, that fell only a little short of a passion, for slipping back and forth through the Confederate lines. In all my experience with him I never saw him frightened, nor even ruffled; and, to the best of my knowledge, he never was hungry nor tired—although I have seen him amazingly thirsty.

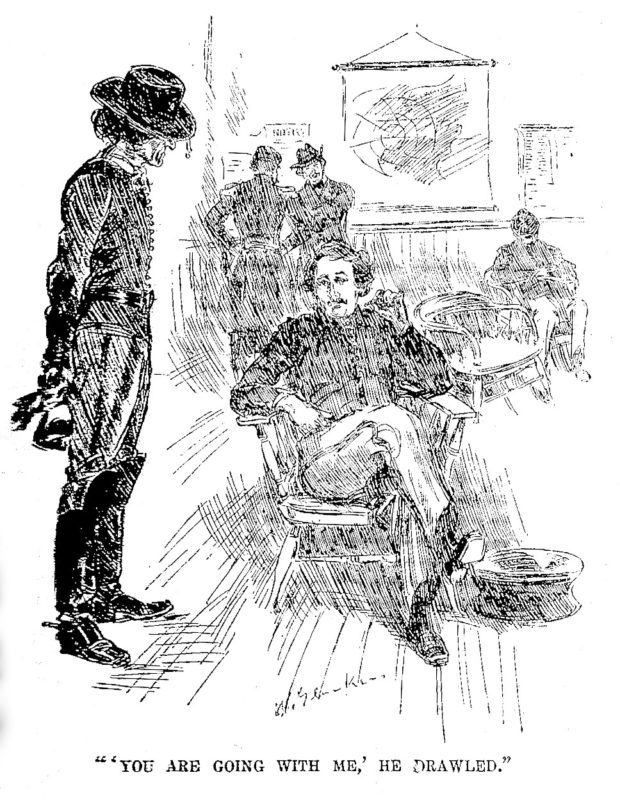

I had been lounging in the waiting-room one night for upwards of an hour, when Traill came out of the Colonel’s private office and closed the door gently behind him. “You are going with me,” he drawled; “I have ordered up the horses.”

One thing a military man learns early in his career—not to ask questions until there is a fair likelihood of having them answered—and I followed Traill’s preparations in silence. He selected three revolvers, and twirled the chambers of each of them and clicked the triggers to make sure that they were in good working order. Two of them he loaded, thrust deftly into the holsters of his belt, and buckled the leather flaps down over them; the third he slid into the slack of his cavalry boot. Then he rolled a blue army blanket inside of his poncho, and drew the bundle into wrinkled ridges with thongs of leather. A certain silent swiftness and gentleness marked everything that Traill did.

It was a dark night. We crossed the Long Bridge at a sharp trot, and climbed the Virginia hills. The road was soggy with moist sand that slipped ad clogged under the hoofs of our horses—like riding in an oats bin, Traill said. For miles the road crooked through the pine woods, and, as we moved, the trees seemed to march up out of the darkness, present themselves like soldiers on parade, then wheel backwards again, and give place to other companies and battalions. The spring air was heavy and pungent with the smell of moist mold, and in the hollows almost sharp with the lingering coolness of winter. I had no idea where we were going. Traill galloped steadily at my side, saying nothing. He was a man of few words, although by no means sullen.

“I haven’ heard the nature of our mission,” I said to him: I felt that the auspicious moment for asking questions had come.

“We’re going out to get Captain Cameron,” he answered shortly.

I had heard much of Captain Cameron even during the short time I had been in Washington. He was a young Southern officer, born of a well-known Virginia family. Early in the war he became a violent Confederate, and, from his intimate knowledge of the country about Washington, he was assigned to the work of spy and blockade-runner. He was related by ties of blood more or less direct to half the aristocracy of Virginia and Maryland, and when we went out after him, we found that he had as many holes as a gopher. Ever since the opening of hostilities the authorities at Washington had sought to effect his capture; but a year of the war had passed, and he was still spreading terror along the Potomac. His finger, so said common fame, was always crooked to the trigger of his pistol, and more than once his reckless daring had cost the life of soldiers sent out to trap him. Report added to his reputation for bravado by arming him always with a bowie-knife, which he had used on several occasions with bloody effect.

Beyond Alexandria, where we halted a moment while our horses plunged their noses into a watering-trough, the country grew more desolate and forbidding. Many of the plantation buildings had been deserted, and they loomed up black and forlorn in the darkness. Sometimes a dog howled from the negro quarters in the rear, and dismal echoes responded from plantation to plantation as we passed.

The first incident of the night worth mentioning—and it nearly cost the success of our expedition—occurred just after we tightened our saddle-girths for the third time, about midnight, as I judged. We knew that the country swarmed with Confederate guerrillas, but it was never the custom of the Secret Service to give them even the passing compliment of anxiety. We had stopped at a cross-roads, and Traill had thrown his bridle-rein to me while he went down on his knees and crept across the road, feeling for the wagon tracks: he was not quite certain in the darkness which road to take. In a moment there came a voice so sudden and sharp that it seemed to split the darkness: “Halt! Who comes there?”

Traill leaped to his saddle without a word. We drove the spurs into our horses’ flanks, hugged close to their reeking necks, and galloped up the road. We heard a sharp command, then the sound of heating hoofs behind us. A revolver shot rang out sharply in the night air, and we heard the wailing cry of the bullet as it passed over our heads.

We were riding up a long hill. At the top, cut in silhouette against the sky, I saw the form of a horseman sitting statue-like at his post. We were evidently surrounded. Before I could speak, Traill laid his hand on my bridle-arm.

“Turn in here,” he said.

We swerved wildly to the right, into what seemed an impenetrable forest, and rode a hundred yards or more in imminent danger of being brushed from our saddles by the down-sweeping limbs of the trees. Then the horses came to an abrupt standstill, and we narrowly escaped pitching headlong into a deep ravine that yawned before us. As we paused, we could hear the sound of hoofs in the road, then the sudden fierce challenge of the vedette, then voices in conversation. Traill grasped the nose of his horse, to prevent a tell-tale whinny.

A moment only we waited; then we scrambled down into the ravine, our horses sliding after us, and made our way around the vedette, striking the road again less than a mile further to the south.

“A narrow escape,” I commented, as our horses’ hoofs again beat the steady music of the gallop.

Traill laughed. “There was only a handful of ’em or they would have given us a harder rub,” he said.

Once more we hitched our saddle-girths, this time without dismounting, for time was precious, and rode in silence for an hour or more. At length Traill drew rein near a high arched gateway of the kind so familiar in the ante-bellum South. Then he swung from his saddle and knelt close to one of the ghostly white columns, parted the weeds about its base, and struck a match. It lit up his face for a single instant, and then went out.

“This is the place,” he said; “I have found O’Dell’s mark.”

To this day I do not know the exact location of the plantation, but of this I am certain: it was in Prince William County, not far from the Potomac River. It took us upwards of four hours of hard riding to reach it. The gate was locked, but I wrenched loose two of the boards from the dilapidated fence, and we rode up the long, winding lane, guiding our horses to the grass at the edge of the drive, that they might make no noise.

It was a beautiful old place, even as we saw it, by dead of night. Great spreading trees covered the knoll on which it stood, and their branches, reaching out over the wide verandas, swept the gutter eaves.

The building had every appearance of being deserted—a great, black, silent block of uncertain shadows. The blinds were drawn, and not a ray of light gleamed anywhere from its windows, or from the negro quarters, which we could see dimly huddled together half a hundred yards to the rear. There was not even a dog to bark, nor a sleeping negro to waken and cry out.

“The house is vacant,” I said to Traill , as we tossed our reins over the pegs on the hitching-bar.

“No, it isn’t,” he answered with some positiveness.

We stood under a syringa bush that half hid the wide front door.

“Have you got your pistols?”

“Yes, “ I said, drawing one of them from its holster and feeling for the loads.

“Go round to the rear of the house. Take care to make no noise. You will find a wide back porch. Go up and stand on the steps, near the back door, so that you can cover all the windows. If anyone tries to leave the building, shoot ’em.” Traill said it softly, almost gently.

“That man Cameron,” he cautioned, as I was starting, “is a good deal of a fighter; he’s quick on the trigger.”

I went to the rear. I remember I was lame and moist from riding, and that my fingers clutched the revolver handle until my wrist throbbed with pain. It was the hour of night when a man’s blood doesn’t run the bravest, especially if he isn’t sure what odds he may have to meet, or whether a shot from a darkened window may not drop him in his tracks.

I went to the rear. I remember I was lame and moist from riding, and that my fingers clutched the revolver handle until my wrist throbbed with pain. It was the hour of night when a man’s blood doesn’t run the bravest, especially if he isn’t sure what odds he may have to meet, or whether a shot from a darkened window may not drop him in his tracks.

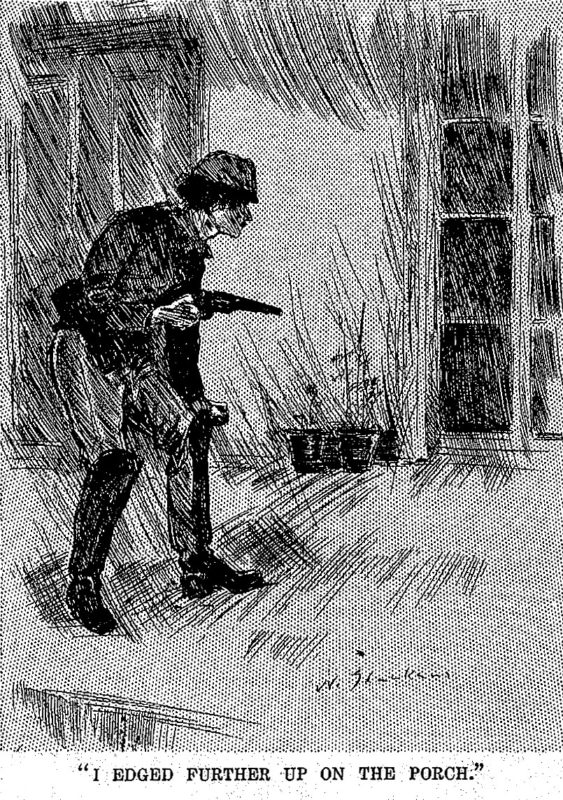

My sense of hearing was painfully acute. I distinctly heard the squeaking of Traill’s boots and the metallic tinkle of his spurs as he mounted the front porch, and then the resonant echo of his summons on the iron knocker. Like many Southern mansions, the house was built with a wide hall running straight through from the front to the back door. For a moment I fancied I heard the cautious squeak of steps on the stairs within, and then all was still again. I edged further up on the porch, that I might better command a wide, shutterless window at the right of the door. There is this terror in a dark window: those within may see out, while those without cannot see in; but you don’t appreciate it until you imagine a desperate man inside, waiting to put a bullet through your jacket.

There came a second and much louder knock on the front door. I knew that Traill was using his pistol butt. The sound echoed and reechoed through the big, silent building. Presently I heard a shutter creak somewhere at the front of the house, and I set the hammer of my other revolver. A woman’s voice spoke; I could not catch the words.

“Never mind, come down here and open the door,” I heard Traill reply.

There was another parley, and then the shutter creaked again in closing. A moment later I saw through the glass of the side-light the glimmer of a candle, with its sharp shadows creeping in huge angles along the ceiling of the hall.

“Who is there?” asked a frightened, feminine voice.

I heard a chain jingle and the sliding of a bar, and then voices in low conversation. Traill was speaking:

“I tell you he’s here, and I’m going to have him. He can’t get away.”

“He is not here; I tell you he is not here. You have come to the wrong place.”

The woman’s voice was wonderfully calm and clear, and I mentally decided that Traill had made a mistake. Then I heard a sharp whistle, the signal agreed upon, and I ran around to the front door.

“All quiet out there?” asked Traill, speaking in a loud voice. “Are the men all stationed?”

“Yes, sir; the sergeant has every window covered.”

As I said this, I fancied I saw the corners of the woman’s mouth twitch just a little, and she drew herself together as if she felt the cold. She was past middle age, with the beauty of the South yet clear in her face, and a cold, fearless black eye. In spite of her hurried toilet, she carried herself proudly, as if accustomed to be obeyed.

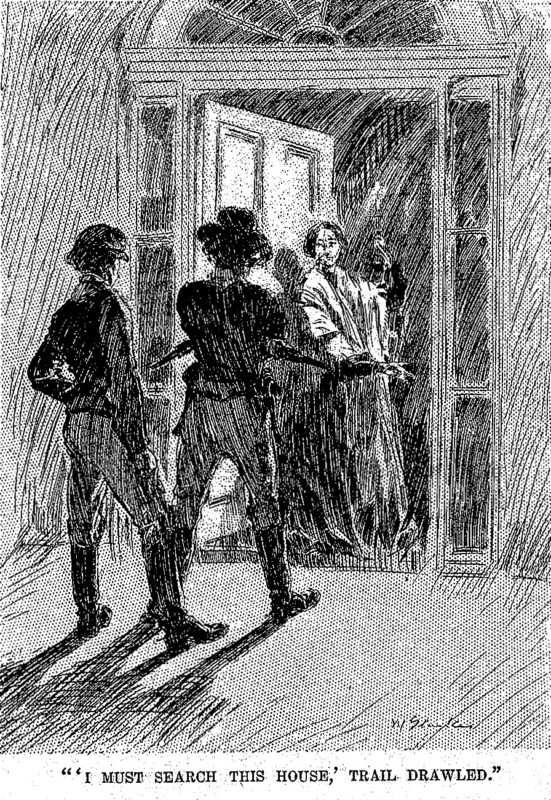

“I must search this house,” Traill drawled gently.

“There is nothing here,” she answered; “you can search it if you care to.”

As she threw open the door of the drawing-room she was as calm and dignified as if ushering a company of guests to some grand dinner.

The house was much dismantled, but it still showed traces of its former estate. There yet remained a few fine old paintings on the walls, and the furniture—what was left of it—was of carved mahogany. Traill examined the desks and wall cases, and peered into the fireplace and up the chimney. From the kitchen we stooped our way down a narrow passage into the cellar. The woman led, holding a candle high, and I covered the rear, revolver in hand. We found butter-tubs, apple-barrels, and wine-cases, long since empty, but there was no trace of our quarry.

The house was much dismantled, but it still showed traces of its former estate. There yet remained a few fine old paintings on the walls, and the furniture—what was left of it—was of carved mahogany. Traill examined the desks and wall cases, and peered into the fireplace and up the chimney. From the kitchen we stooped our way down a narrow passage into the cellar. The woman led, holding a candle high, and I covered the rear, revolver in hand. We found butter-tubs, apple-barrels, and wine-cases, long since empty, but there was no trace of our quarry.

“What is in here?” asked Traill, when we again reached the wide hall.

“That is the chapel; there is nothing in there that you want. Surely you will not desecrate the chapel ?”

“I’ll see,” said Traill.

As the woman threw open the door, I remember thinking how easy it would be for a man hidden within to kill us both as we stood there with our arms down and the candlelight in our eyes. It was the only room in the house that had not been dismantled—a high, somber room with Gothic furnishings and all the fittings of a private chapel. Traill searched every nook and corner. At the altar he paused, and poked his pistol under the embroidered curtain. I saw the woman’s face flame red and then fade swiftly white again. Traill laughed softly. Hanging to the altar sides in regular rows were twenty carbines.

“You can have them,” said the woman coldly.

“I am here for Captain Cameron,” was Traill’s response.

The search went on uninterrupted. In one of the upper rooms—the room occupied by the mistress of the house—we found a terrified mulatto girl crouching and praying.

“Is Captain Cameron here?” Traill asked her suddenly, his face glaring close to hers.

She glanced at her mistress fearfully.

“Fo’ de Lawd, he ain’t yere. He done gone ’way las’ week. Fo’ de Lawd, I ain’t seen nothin’ ob him.”

“So he has been here,” said Traill quietly.

“Yes, he has,” was the woman’s response, her voice still clear and steady; “but, as the girl says, he has gone away.”

Traill paused in the upper hallway. I knew he was perplexed. “Do you mean to tell me that you are the only person in this house?”

“The only white person, and this girl is the only negro—the others have all been stolen by your army,” and the fire of the South blazed up in her eyes, and died away again as swiftly as it came.

Just then I caught the outlines of a square trap-door in the high ceiling at the further end of the hall. I touched Traill’s shoulder, and pointed it out. His eyes flashed, and I saw the jagged white scar on his cheek twitch and color.

“How do you get up there?” he asked, fixing his eyes on the woman’s face.

“We don’t get up,” she answered steadily; “we haven’t had the place open for years.”

Traill turned to me. “Get that table out of the bedroom.”

I pulled it out, taking care to make no noise, and placed it under the trap. Traill jumped upon it, but he could not reach the ceiling. The woman had followed us as if fascinated. She leaned against the wall, and looked up, with a sarcastic smile curling her lips.

“Do you intend to go up there?” she asked, and there was a hint of the sarcasm in her voice.

“Certainly,” said Traill.

“If Cameron was in that attic, do you suppose you would come down alive ? You evidently have not made the acquaintance of Captain Cameron.”

She spoke steadily, but her fingers were knotted and twisted together, and I remember observing that the nails were blue.

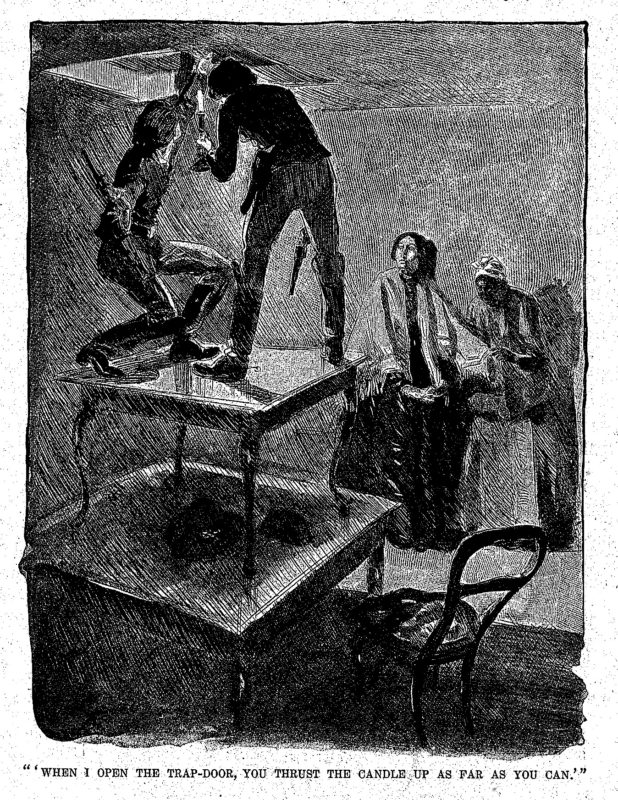

I brought another table—a smaller one—and placed it on top of the first.

“Jump up here,” said Traill. “Hand up the candle.”

I climbed up beside him. I remember observing, with the minuteness of attention that comes with moments of great intensity, that Traill’s cavalry spurs were scratching the polish of the mahogany. We were now both standing on the narrow top table, stooping over, with our heads close to the ceiling. The woman’s lips had dropped open, and there was such a look of horrified interest in her face as I hope I may never see again. Traill handed me the candle.

“Is your pistol ready?” he asked quietly.

“That man is up here. He is probably awake and ready for us. When I open the trapdoor, you thrust the candle up as far as you can. If he shoots me, you kill him.”

“What if there are other men with him?”

Traill shrugged. “Ready?” he asked.

“Ready,” I answered.

Traill straightened upward, and threw back the trap-door. Both of us rose through the opening together. As I raised the candle, my hand grazed the shaggy face of a man in Confederate uniform, who was leaning almost over us. By the stare of his eyes, he had just wakened from a heavy sleep.

Within a breath I was looking into a black hole with a gleaming rim around it. Traill had no time to raise his pistol. I heard the click-click of a hammer drawn sharply back. Traill bent forward and grasped the handle of a bowie-knife sheathed at the other man’s belt. A flash of steel in the candle-light, a swift lunge of the arm, and I felt the hot blood spatter in my face. The pistol rattled to the loose boards of the attic. With a sobbing in-drawing of the breath, the man lurched forward, quivered convulsively, and then lay quite still. I saw the useless fingers loosen their clutch, and a little dark fountain playing about the knife-handle and spreading on the white shirt-bosom. The blade had reached the heart. While this happened no one spoke.

“Now we will get down,” said Traill almost gently.

The woman leaned stiffly against the wall. Her face was a ghastly blank, neither interest, nor fear, nor hatred in its lines.

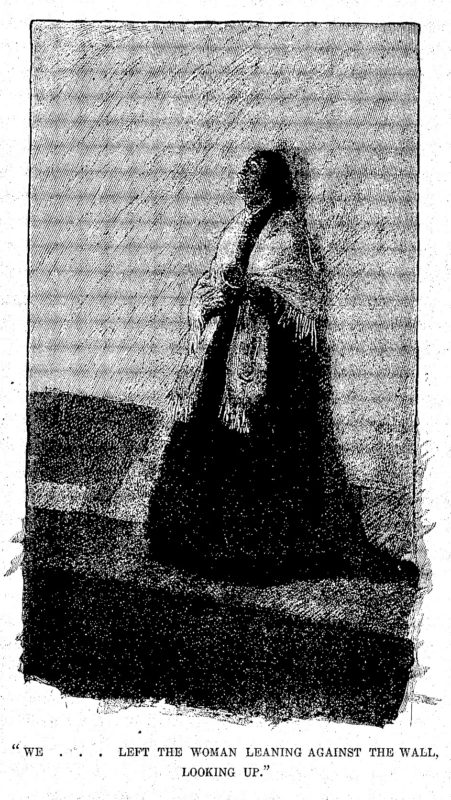

“What have you done?” she whispered. Traill glanced upward. On the dingy plastering, near the gaping trap-door, a red spot was slowly widening. There was no outcry, no confusion. “No use in staying here,” said Traill.

We went down the stairway, and left the woman leaning against the wall, looking up. Ten miles we rode without saying a word, and then, just as the dawn was breaking through the scrubby yellow pines, we drew rein on our gaunt and lather-gray horses. There was a little creek at the roadside, and we stooped to drink. I looked at Traill’s face. It was studded with black blotches; so was his gray coat. “Am I bloody?” I asked.

We went down the stairway, and left the woman leaning against the wall, looking up. Ten miles we rode without saying a word, and then, just as the dawn was breaking through the scrubby yellow pines, we drew rein on our gaunt and lather-gray horses. There was a little creek at the roadside, and we stooped to drink. I looked at Traill’s face. It was studded with black blotches; so was his gray coat. “Am I bloody?” I asked.

“Yes,” he answered.

And then my knees gave way under me, and I shook with the horror of my first killing. I could not control the trembling of my hand when I tried to wash away the blood. Traill looked at me.

“Never mind,” he said quietly, “ it could not be helped; it was death to him or death to us. We took the only course.”

“Was that woman Cameron’s mother?”

“She said she wasn’t.”

“But she was?”

“Yes.” Traill dabbled his hands in the water, in his peculiar deft way, but his face showed no emotion.

At noon we reached Washington. I followed Traill into the Colonel’s private office, weary of body and wretched of soul.

“Well?” questioned the Colonel.

“We got Captain Cameron,” drawled Traill.

More than ten years afterward, although I had seen more than one bloody battle-field later in the war, I woke up sometimes with the picture of that woman standing there alone, looking up, still distinct in my mind.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

By subscribing, you will automatically receive the latest episodes downloaded to your computer or portable device. Select your preferred subscription method above.

To subscribe via a different application: Go to your favorite podcast application or news reader and enter this URL: https://clearwaterpress.com/byline/feed/podcast/

Comments are closed.

Really interesting stuff. This is a great podcast to draw to. I can’t wait for the next episode!

Thanks, Lydia!