War Correspondents

Episode 4 •

War Correspondents

• The war correspondents who were sent to this war knew it was to sound their death-knell. The newspapers that had no correspondents at the front told them so…

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Email | TuneIn | RSS

SHOW NOTES ____________

War Correspondents

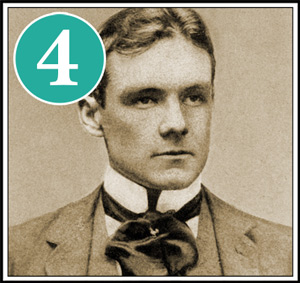

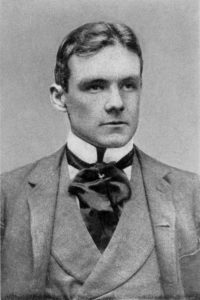

By Richard Harding Davis

1914

The attitude of the newspaper reader toward the war correspondent who tries to supply him with war news has always puzzled me.

One might be pardoned for suggesting that their interests are the same. If the correspondent is successful, the better service he renders the reader. The more he is permitted to see at the front, the more news he is allowed to cable home, the better satisfied should be the man who follows the war through the “extras.”

But what happens is the reverse of that. Never is the “constant reader” so delighted as when the war correspondent gets the worst of it. It is the one sure laugh. The longer he is kept at the base, the more he is bottled up, “deleted,” censored, and made prisoner, the greater is the delight of the man at home. He thinks the joke is on the war correspondent. I think it is on the “constant reader.” If, at breakfast, the correspondent fails to supply the morning paper with news, the reader claims the joke is on the news-gatherer. But if the milkman fails to leave the milk, and the baker the rolls, is the joke on the milkman and the baker or is it on the “constant reader”? Which goes hungry?

The explanation of the attitude of the “constant reader” to the reporters seems to be that he regards the correspondent as a prying busybody, as a sort of spy, and when he is snubbed and suppressed he feels he is properly punished. Perhaps the reader also resents the fact that while the correspondent goes abroad, he stops at home and receives the news at second hand. Possibly he envies the man who has a front seat and who tells him about it. And if you envy a man, when that man comes to grief it is only human nature to laugh.

You have seen unhappy small boys outside a baseball park, and one happy boy inside on the highest seat of the grand stand, who calls down to them why the people are yelling and who has struck out. Do the boys on the ground love the boy in the grand stand and are they grateful to him? No.

Does the fact that they do not love him and are not grateful to him for telling them the news distress the boy in the grand stand? No. For no matter how closely he is bottled up, how strictly censored, “deleted,” arrested, searched, and persecuted, as between the man at home and the correspondent, the correspondent will always be the more fortunate. He is watching the march of great events, he is studying history in the making, and all he sees is of interest. Were it not of interest he would not have been sent to report it. He watches men acting under the stress of all the great emotions. He sees them inspired by noble courage, pity, the spirit of self-sacrifice, of loyalty, and pride of race and country.

In Cuba I saw Captain Robb Church of our army win the Medal of Honor, in South Africa I saw Captain Towse of the Scot Greys win his Victoria Cross. Those of us who watched him knew he had won it just as surely as you know when a runner crosses the home plate and scores. Can the man at home from the crook play or the home run obtain a thrill that can compare with the sight of a man offering up his life that other men may live?

When I returned to New York every second man I knew greeted me sympathetically with: “So, you had to come home, hey? They wouldn’t let you see a thing.” And if I had time I told him all I saw was the German, French, Belgian, and English armies in the field, Belgium in ruins and flames, the Germans sacking Louvain, in the Dover Straits dreadnoughts, cruisers, torpedo destroyers, submarines, hydroplanes; in Paris bombs falling from air-ships and a city put to bed at 9 o’clock; battle-fields covered with dead men; fifteen miles of artillery firing across the Aisne at fifteen miles of artillery; the bombardment of Rheims, with shells lifting the roofs as easily as you would lift the cover of a chafing-dish and digging holes in the streets, and the cathedral on fire; I saw hundreds of thousands of soldiers from India, Senegal, Morocco, Ireland, Australia, Algiers, Bavaria, Prussia, Scotland, saw them at the front in action, saw them marching over the whole northern half of Europe, saw them wounded and helpless, saw thousands of women and children sleeping under hedges and haystacks with on every side of them their homes blazing in flames or crashing in ruins. That was a part of what I saw. What during the same two months did the man at home see? If he were lucky he saw the Braves win the world’s series, or the Vernon Castles dance the fox trot.

The war correspondents who were sent to this war knew it was to sound their death-knell. They knew that because the newspapers that had no correspondents at the front told them so; because the General Staff of each army told them so; because every man they met who stayed at home told them so. Instead of taking their death- blow lying down they went out to meet it. In other wars as rivals they had fought to get the news; in this war they were fighting for their professional existence, for their ancient right to stand on the firing-line, to report the facts, to try to describe the indescribable. If their death-knell sounded they certainly did not hear it. If they were licked they did not know it. In the twenty-five years in which I have followed wars, in no other war have I seen the war correspondents so well prove their right to march with armies. The happy days when they were guests of the army, when news was served to them by the men who made the news, when Archibald Forbes and Frank Millet shared the same mess with the future Czar of Russia, when MacGahan slept in the tent with Skobeleff and Kipling rode with Roberts, have passed. Now, with every army the correspondent is as popular as a floating mine, as welcome as the man dropping bombs from an air-ship. The hand of every one is against him. “Keep out! This means you!” is the way they greet him.

Added to the dangers and difficulties they must overcome in any campaign, which are only what give the game its flavor, they are now hunted, harassed, and imprisoned. But the new conditions do not halt them. They, too, are fighting for their place in the sun. I know one man whose name in this war has been signed to despatches as brilliant and as numerous as those of any correspondent, but which for obvious reasons is not given here. He was arrested by one army, kept four days in a cell, and then warned if he was again found within the lines of that army he would go to jail for six months; one month later he was once more arrested, and told if he again came near the front he would go to prison for two years. Two weeks later he was back at the front. Such a story causes the teeth of all the members of the General Staff to gnash with fury. You can hear them exclaiming: “If we caught that man we would treat him as a spy.” And so unintelligent are they on the question of correspondents that they probably would.

When Orville Wright hid himself in South Carolina to perfect his flying-machine he objected to what he called the “spying” of the correspondents. One of them rebuked him. “You have discovered something,” he said, “in which the whole civilized world is interested. If it is true you have made it possible for man to fly, that discovery is more important than your personal wishes. Your secret is too valuable for you to keep to yourself. We are not spies. We are civilization demanding to know if you have something that more concerns the whole world than it can possibly concern you.”

As applied to war, that point of view is equally just. The army calls for your father, husband, son—calls for your money. It enters upon a war that destroys your peace of mind, wrecks your business, kills the men of your family, the man you were going to marry, the son you brought into the world. And to you the army says: “This is our war. We will fight it in our own way, and of it you can learn only what we choose to tell you. We will not let you know whether your country is winning the fight or is in danger, whether we have blundered and the soldiers are starving, whether they gave their lives gloriously or through our lack of preparation or inefficiency are dying of neglected wounds.” And if you answer that you will send with the army men to write letters home and tell you, not the plans for the future and the secrets of the army, but what are already accomplished facts, the army makes reply: “No, those men cannot be trusted. They are spies.”

Not for one moment does the army honestly think those men are spies. But it is the excuse nearest at hand. It is the easiest way out of a situation every army, save our own, has failed to treat with intelligence. Every army knows that there are men to-day acting, or anxious to act, as war correspondents who can be trusted absolutely, whose loyalty and discretion are above question, who no more would rob their army of a military secret than they would rob a till. If the army does not know that, it is unintelligent. That is the only crime I impute to any general staff—lack of intelligence.

When Captain Granville Fortescue, of the Hearst syndicate, told the French general that his word as a war correspondent was as good as that of any general in any army he was indiscreet, but he was merely stating a fact. The answer of the French general was to put him in prison. That was not an intelligent answer.

The last time I was arrested was at Romigny, by General Asebert. I had on me a three-thousand-word story, written that morning in Rheims, telling of the wanton destruction of the cathedral. I asked the General Staff, for their own good, to let the story go through. It stated only facts which I believed were they known to civilized people would cause them to protest against a repetition of such outrages. To get the story on the wire I made to Lieutenant Lucien Frechet and Major Klotz, of the General Staff, a sporting offer. For every word of my despatch they censored I offered to give them for the Red Cross of France five francs. That was an easy way for them to subscribe to the French wounded three thousand dollars. To release his story Gerald Morgan, of the London Daily Telegraph, made them the same offer. It was a perfectly safe offer for Gerald to make, because a great part of his story was an essay on Gothic architecture. Their answer was to put both of us in the Cherche-Midi prison. The next day the censor read my story and said to Lieutenant Frechet and Major Klotz: “But I insist this goes at once. It should have been sent twenty-four hours ago.”

Than the courtesy of the French officers nothing could have been more correct, but I submit that when you earnestly wish to help a man to have him constantly put you in prison is confusing. It was all very well to dissemble your love. But why did you kick me down-stairs?

There was the case of Luigi Barzini. In Italy Barzini is the D’Annunzio of newspaper writers. Of all Italian journalists he is the best known. On September 18, at Romigny, General Asebert arrested Barzini, and for four days kept him in a cow stable. Except what he begged from the gendarmes, he had no food, and he slept on straw. When I saw him at the headquarters of the General Staff under arrest I told them who he was, and that were I in their place I would let him see all there was to see, and let him, as he wished, write to his people of the excellence of the French army and of the inevitable success of the Allies. With Italy balancing on the fence and needing very little urging to cause her to join her fortunes with France, to choose that moment to put Italian journalists in a cow yard struck me as dull.

In this war the foreign offices of the different governments have been willing to allow correspondents to accompany the army. They know that there are other ways of killing a man than by hitting him with a piece of shrapnel. One way is to tell the truth about him. In this entire war nothing hit Germany so hard a blow as the publicity given to a certain remark about a scrap of paper. But from the government the army would not tolerate any interference. It said: “Do you want us to run this war or do you want to run it?” Each army of the Allies treated its own government much as Walter Camp would treat the Yale faculty if it tried to tell him who should play right tackle.

As a result of the ban put upon the correspondents by the armies, the English and a few American newspapers, instead of sending into the field one accredited representative, gave their credentials to a dozen. These men had no other credentials. The letter each received stating that he represented a newspaper worked both ways. When arrested it helped to save him from being shot as a spy, and it was almost sure to lead him to jail. The only way we could hope to win out was through the good nature of an officer or his ignorance of the rules. Many officers did not know that at the front correspondents were prohibited.

As in the old days of former wars we would occasionally come upon an officer who was glad to see some one from the base who could tell him the news and carry back from the front messages to his friends and family. He knew we could not carry away from him any information of value to the enemy, because he had none to give. In a battle front extending one hundred miles he knew only his own tiny unit. On the Aisne a general told me the shrapnel smoke we saw two miles away on his right came from the English artillery, and that on his left five miles distant were the Canadians. At that exact moment the English were at Havre and the Canadians were in Montreal.

In order to keep at the front, or near it, we were forced to make use of every kind of trick and expedient. An English officer who was acting as a correspondent, and with whom for several weeks I shared the same automobile, had no credentials except an order permitting him to pass the policemen at the British War Office. With this he made his way over half of France. In the corner of the pass was the seal or coat of arms of the War Office. When a sentry halted him he would, with great care and with an air of confidence, unfold this permit, and with a proud smile point at the red seal. The sentry, who could not read English, would invariably salute the coat of arms of his ally, and wave us forward.

That we were with allied armies instead of with one was a great help. We would play one against the other. When a French officer halted us we would not show him a French pass but a Belgian one, or one in English, and out of courtesy to his ally he would permit us to proceed. But our greatest asset always was a newspaper. After a man has been in a dirt trench for two weeks, absolutely cut off from the entire world, and when that entire world is at war, for a newspaper he will give his shoes and his blanket.

The Paris papers were printed on a single sheet and would pack as close as bank-notes. We never left Paris without several hundred of them, but lest we might be mobbed we showed only one. It was the duty of one of us to hold this paper in readiness. The man who was to show the pass sat by the window. Of all our worthless passes our rule was always to show first the one of least value. If that failed we brought out a higher card, and continued until we had reached the ace. If that proved to be a two-spot, we all went to jail. Whenever we were halted, invariably there was the knowing individual who recognized us as newspaper men, and in order to save his country from destruction clamored to have us hung. It was for this pest that the one with the newspaper lay in wait. And the instant the pest opened his lips our man in reserve would shove the Figaro at him. “Have you seen this morning’s paper?” he would ask sweetly. It never failed us. The suspicious one would grab at the paper as a dog snatches at a bone, and our chauffeur, trained to our team-work, would shoot forward.

When after hundreds of delays we did reach the firing-line, we always announced we were on our way back to Paris and would convey there postal cards and letters. If you were anxious to stop in any one place this was an excellent excuse. For at once every officer and soldier began writing to the loved ones at home, and while they wrote you knew you would not be molested and were safe to look at the fighting.

It was most wearing, irritating, nerve-racking work. You knew you were on the level. In spite of the General Staff you believed you had a right to be where you were. You knew you had no wish to pry into military secrets; you knew that toward the allied armies you felt only admiration—that you wanted only to help. But no one else knew that; or cared. Every hundred yards you were halted, cross-examined, searched, put through a third degree. It was senseless, silly, and humiliating. Only a professional crook with his thumb-prints and photograph in every station-house can appreciate how from minute to minute we lived. Under such conditions work is difficult. It does not make for efficiency to know that any man you meet is privileged to touch you on the shoulder and send you to prison.

The destruction of Yser

This is a world war, and my contention is that the world has a right to know, not what is going to happen next, but at least what has happened. If men have died nobly, if women and children have cruelly and needlessly suffered, if for no military necessity and without reason cities have been wrecked, the world should know that.

Those who are carrying on this war behind a curtain, who have enforced this conspiracy of silence, tell you that in their good time the truth will be known. It will not. If you doubt this, read the accounts of this war sent out from the Yser by the official “eye-witness” or “observer” of the English General Staff. Compare his amiable gossip in early Victorian phrases with the story of the same battle by Percival Phillips; with the descriptions of the fall of Antwerp by Arthur Ruhl, and the retreat to the Marne by Robert Dunn. Some men are trained to fight, and others are trained to write. The latter can tell you of what they have seen so that you, safe at home at the breakfast table, also can see it. Any newspaper correspondent would rather send his paper news than a descriptive story. But news lasts only until you have told it to the next man, and if in this war the correspondent is not to be permitted to send the news I submit he should at least be permitted to tell what has happened in the past.

This war is a world enterprise, and in it every man, woman, and child is an interested stockholder. They have a right to know what is going forward. The directors’ meetings should not be held in secret.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

By subscribing, you will automatically receive the latest episodes downloaded to your computer or portable device. Select your preferred subscription method above.

To subscribe via a different application: Go to your favorite podcast application or news reader and enter this URL: https://clearwaterpress.com/byline/feed/podcast/