The Heart Wife

Episode 15 •

The Heart Wife

• The reason for all the knavery was to avoid the payment of three hundred dollars to a destitute and distracted woman—that, and that alone!

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Email | TuneIn | RSS

SHOW NOTES ____________

The Heart Wife

By Upton Sinclair

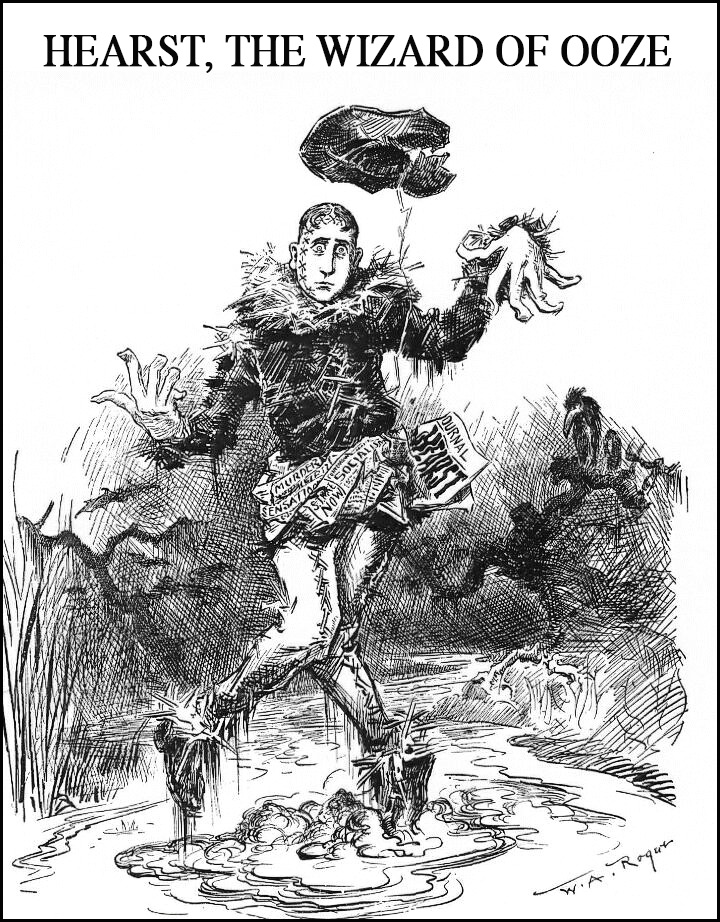

The next story has to do with the phenomenon known as “Hearst Journalism.” It is a most extraordinary story; in its sensational elements it discounts the most lurid detective yarn, it discounts anything which is published in the Hearst newspapers themselves. At first the reader may find it beyond belief; if so, let him bear in mind that the story was published in full in the “New York Call” for August 9, 1914, and that no one of the parties named brought a libel suit, nor made so much as a peep concerning the charges. I may fairly assert that this story of “Hearst Journalism” is one which Mr. Hearst and his editors themselves admit to be true.

William Randolph Hearst has been at various times a candidate for high office in America, and has been able to exert much influence on the course of the Democratic party — in New York, in Illinois, and even throughout the nation. What are the Hearst newspapers ? How are they made ? And what is the character of the men who make them? These questions seem to me of sufficient importance to be worth answering in detail.

In order to make matters clear from the outset, let me point out to the reader that, for once, I am not dealing with a grievance of my own. Throughout this whole affair my purpose was to get some money from a Hearst newspaper, but I was not trying to get this money for myself; I was trying to get it for a destitute and distracted woman. All parties concerned knew that and knew it beyond dispute. The wrong was done, not to me, but to a destitute and distracted woman, and so I can present to the reader a case in which he can not possibly attribute an ulterior motive to me.

The story began at Christmas, 19l3. In the New York papers there appeared one day an account of the death of a lawyer named Couch, in the little town of Monticello, N. Y. This man was nearly 60 years old, a cripple and eccentric, who lived most of the time in his little office in the village, going once a week to the home upon the hill where lived his wife and family. The news of his death in the middle of the night was brought to a physician by a strange, terrified woman, who was afterwards missing, but next day was discovered by Mr. Couch’s widow and daughter, cowering in an inner portion of his office, which had been partitioned off to make a separate room.

Investigation was made, and an extraordinary set of circumstances disclosed. The man and woman had been lovers for fifteen years, and for the last three years the woman had spent her entire time in this walled-off room, never going outside, never even daring to go near the window in the daytime. This sacrifice she had made for the sake of the old man, because she had been necessary to his life, and there was no other way of keeping secret a situation which would have ruined him.

The story seemed to make a deep impression upon the public, at least if one could judge from the newspapers. There were long accounts from Monticello day by day. The woman was described as grief-stricken, terrified by her sudden confrontation with the world.

She was taken to the county jail and kept there until after the dead man’s funeral. No charges were brought against her, but she remained in jail because she had nowhere else to go, and because her condition was so pitiful that the authorities delayed to turn her out. She was helpless, friendless, with but one idea, a longing for death. She was besieged by newspaper reporters, vaudeville impresarios and moving picture makers, to all of whom she denied herself, refusing to make capital of her grief. She was described as a person of refinement and education, and everything she said bore out this view of her character. She was, apparently, a woman of mature mind, who had deliberately sacrificed everything else in life in order to care for an unhappy old man whom she loved, and whom she could not marry because of the rigid New York divorce law.

One morning the papers stated that the relatives of this “hidden woman” refused to offer a home to her. My wife wrote to her, offering to help her, provided this could be done without any publicity; but time passed without a reply. My wife was only three or four weeks out of the hospital after an operation for an injury to the spine. We had made plans to spend the winter in Bermuda, to give her an opportunity to recuperate, and our steamer was to sail at midnight on Monday. On Sunday morning, while I was away from home, my wife was called on the phone by Miss Branch, who announced that she had left the Sullivan County jail, and was at the ferry in New York, with no idea what to do — except to leap off into the river. My wife told her to take a cab and come to our home, and sent word to me what she had done.

Not to drag out the story too much, I will say briefly that Miss Branch proved to be a woman of refinement, and also of remarkable mind. She has read widely and thought for herself, and I have in my possession a number of her earlier manuscripts which show, not merely that she can write, but that she has worked out for herself a point of view and an attitude to life. She was one of the most pitiful and tragic figures it has ever been our fate to encounter, and the twenty-four hours which we spent in trying to give her comfort and the strength to face life again will not soon be forgotten by either of us.

We interested some friends. Dr. and Mrs. James P. Warbasse, in the case, and they very generously offered to place Miss Branch in a sanitarium. Before she left she implored me to make a correction of certain misstatements about her which had appeared in the papers. She was deeply grieved because of the shame she had brought upon her brother and his family, and she thought their sufferings might be partly relieved if they and others read the truth about her character and motives.

At this time, it should be understood, Miss Branch was the newspaper mystery of the hour. She had vanished from Monticello, and on Monday morning the newspapers had nothing on the case but their own inventions. I sought the advice of a friend, J. O’Hara Cosgrave, a well known editor, who suggested that the story ought to be worth money. “As you say that Miss Branch is penniless, why not let one of the papers buy it and pay the money to her? The ‘Evening Journal’ has been playing the story up on the front page every day. Sell it to them.”

I said, “You can’t sell a newspaper a tip without first telling them what the story is—and can you trust them?”

He answered, “I personally know Van Hamm, managing editor of the ‘Evening Journal,’ and if you will make it a personal matter with him, you can trust him.”

“Are you sure?” I asked.

“Absolutely,” he replied.

I talked the matter over with my wife, who was much opposed to the suggestion, refusing to believe that any Hearst man could be trusted. They would betray me, and use my name, and we should be in for disagreeable publicity. Moreover, Miss Branch would never get the money, unless I got a contract in writing. I answered that there was no time to get it in writing. It was then about one o’clock in the afternoon, and the matter would have to be arranged over the phone at once, if it were to be of any use to an evening paper. So finally my wife consented to the attempt being made, upon the definite understanding that she was to stand beside me at the telephone and hear what I said, and that I was to repeat every word the party at the other end of the wire said, in such a way that both he and she would hear the repetition. In this way she would be a witness to the conversation.

And now, as everything depends upon the question of what was said, let me state in advance that this conversation was written down from the memory of both of us a few hours afterward, and that we are prepared, if necessary, to make affidavit that every word of it was spoken, not once, but several times; that the various points covered in it were repeated so frequently and explicitly that the party at the other end of the wire once or twice showed himself annoyed at the delays. The conversation was as follows:

“Is this Mr. Van Hamm, managing editor of the ‘Evening Journal’ ? Mr. Van Hamm, I have called you up because Jack Cosgrave has told me that you are a man who can be trusted. I wish to ask you if you will give me your word of honor to deal fairly with me in a certain matter. I have some information to offer you which will make a big story. I am offering to sell it for a price, and I wish it to be distinctly understood, in advance, beyond any possible question, that you may have this story if you are willing to pay the price. If you don’t want to pay the price, I have your word of honor that you will not in any manner whatever use any syllable of what I tell you.”

This was repeated and agreed to, and then I told him what I had. “I am not at liberty to tell you where Miss Branch is at present,” I said. “I am offering you a story, and a statement which she desires me to give out for her. The price for it is three hundred dollars for Miss Branch. I don’t want the money myself — I won’t even handle it. Is the price agreeable to you?”

The answer was, “Yes, I will send a man up at once.”

I said, “It is distinctly understood that you are to publish nothing whatever about this matter unless the sum of three hundred dollars is paid to Miss Branch?”

“Yes. Where is she, so that I can pay the money to her?”

“I will give you the name of a man who knows where she is. This man will take the money and will bring you her receipt. I wish to give you the name of this man in confidence, for he does not wish his name brought into the case in any way.”

The answer was: “Put the name of the man in a sealed envelope and give it to the reporter, who will give it to me. I will personally see that the money is sent to him, and then will forget his name.”

“Very well,” I replied, and added, “I have written a thousand-word article discussing the case. I will give you this article along with the rest of the information. But you must not print either this article or a single word about this matter unless you pay three hundred dollars to Miss Branch. You understand that distinctly?”

He replied, “I understand. A man will be up to see you in half an hour.”

Fifteen minutes after the conversation there came a telephone-call; a voice, sharp and determined, at the other end of the wire, “Is Miss Branch there ?” My wife was answering the phone and she beckoned to me. We stared at each other, uncertain what to answer or what to think.

“Miss Branch?” said my wife. “No! Certainly Miss Branch is not here.”

“Then where is she?” came the next question, imperative and urgent.

” I do not know,” said my wife. “Who are you ?”

“I have been sent by Sheriff Kinnie, of Sullivan County Jail, who has an important message to be delivered to Miss Branch at once.”

Said I (taking the phone) : “Have you credentials from Sheriff Kinnie?”

“No,” was the reply, “I have not.”

“Then,” I said, “you cannot see Miss Branch.”

“But,” said the voice, “I must see her at once. It is really very important.”

“Come here and see me,” I said.

“No,” was the answer, “I cannot. Please tell me where Miss Branch is. It is a matter of the utmost urgency to Miss Branch herself.”

This went on for several minutes, and, finally, having made sure he could get nothing further, the man at the other end of the wire made an appointment to see me at 5 :30 P. M.

As soon as I hung up the receiver my wife said: “That is a newspaper reporter. Some other paper knows about her.”

But how could this be ? Miss Branch had assured us that she had not mentioned our names to any one, nor shown the letter we had written to her; that no one in Monticello had the remotest idea where she was going, not even the kind sheriff ; that no one had boarded the train at her station. She had been most careful, because my wife in her letter had laid such stress upon her distaste for publicity.

Of course, if other papers had the story of her having come to us, then Miss Branch would not get the money from Mr.” Van Hamm. I had sold an exclusive story, and it would be said that I had not delivered the goods. I at once telephoned to Mr. Van Hamm to tell him of this incident, but I was told that he was out, and I left word for him to call me up the minute he returned.

His reporter arrived, Mr. Thorpe by name. I will say for Mr. Thorpe that I think he tried to be decent all through this ugly matter. I detected in him before it was over the manner of a man who has been sent to do a job he does not like. I explained to him that I had just had a call from a man I suspected to be a reporter, and therefore I would not give him the story until I had had another talk with Mr. Van Hamm and explained the circumstances to him. So Mr. Thorpe sat for awhile in conversation with me. My wife came out and talked to him—much to my surprise, for she has a dread of reporters. Soon, however, I discovered that it was my wife who was doing the interviewing. She called me out of the room and said: “That telephone call was from the ‘Journal’ office.”

“How do you know ?” I asked.

“From everything this young man says, and from his manner. I’ve tried to make him answer me, whether Mr. Van Hamm could have been responsible for that telephone call, and he evaded the question.”

“But,” I said, “what object could they have?”

“They may have been trying to probe you. They have believed that Miss Branch is still with us. This man is trying to find out right now, for he cranes his neck and peers every time I open a door.”

I did not think this could be, but I was more than ever determined to have another talk with Mr. Van Hamm. However, this gentleman continued to be mysteriously absent. I will sum up this aspect of the matter by saying that he continued to be “expected every few minutes” at his office and at his home until 12 o’clock that night. I made not less than twenty efforts to get him, but he would not even let me hear his voice.

As I still refused to give up my story, Mr. Thorpe was suddenly seized with a desire for cigarettes, and went out to purchase some. I am not in a position to say that he called up the office, and turned in what information he had been able to get in the course of our conversation. I will only say that such information appeared an hour or two later in the columns of the Evening Journal.

Mr. Thorpe returned, and still Mr. Van Hamm was mysteriously missing. At last I got tired of waiting, and I gave Mr. Thorpe the interview and the article, and also a letter addressed to Mr. Van Hamm, in which I explicitly repeated the specifications of my telephone conversation with him. I read it to Mr. Thorpe and my wife.

It was then time for the mysterious stranger to appear, but needless to say, he did not keep his appointment. I will conclude this aspect of the story by quoting the following letter from Sheriff Frank Kinnie, of Sullivan County, N. Y.

Your favor relative to Miss Branch received this morning and wish to state that the statement is a falsehood absolutely, as I had no idea whatever as to Miss Branch’s whereabouts, and if you meet Miss Branch she will tell you that no one here in her confidence knew where she was going. I trust a kind Providence will protect and care for her.

To continue: I had that evening to attend a reception given to the delegates of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society, at the home of a friend of mine who conducts a boarding school for young ladies. Little dreaming what an avalanche I was to bring down upon the head of this unfortunate friend, I left word at the office that Mr. Van Hamm was to call me at this school at 8 o’clock that evening.

My wife and I then proceeded to pack our belongings for the steamer — the first opportunity we had had in all this excitement. The superintendent of the apartment-house came to us to ask if we could leave an hour earlier than we had intended, as there were two gentlemen who had rented it and wanted to move in immediately. My wife said: “Surely no one can move into an apartment in the state of disorder in which we are leaving this!”

“It seems strange,” was the reply, “but that is what they want to do. They do not want to wait to have it put in order. They are waiting, and they want to come in the minute you leave.”

If I had been dealing with Hearst newspapers for a sufficiently long time, I would have understood in advance the significance of this phenomenon. As it was, I simply pitied the two unfortunate young men, who would have to spend the night in the midst of the chaotic mass of torn manuscripts and scraps of letters and envelopes which littered the floor. Later on I was glad that I had married a lawyer’s daughter — when my wife informed me she had gone over this trash and burned every scrap of paper relating to Miss Branch and her affairs!

I went to the reception, and at about 8 o’clock in the evening the “Journal” called me up — “Mr. Williams” on the wire — to say that Mr. Van Hamm had considered my article and regretted to say that he could not use it. The information that I had offered him was not considered worth the sum of three hundred dollars. I asked what it was worth, and was told twenty-five dollars. I said, “That won’t do. I will offer it somewhere else.” I demanded the right to speak to Mr. Van Hamm himself on the subject, but was told that he was “out.” I was obliged to content myself with impressing upon “Mr. Williams” the fact that not a syllable that I had confided to Mr. Van Hamm was to be used by the “Journal.”

“Mr. Williams” solemnly assured me that my demand would be complied with — and this in face of the fact that the last edition of the “Evening Journal,” containing the whole story, was then in the “Journal” wagons, being distributed over the city! I called up a friend of mine on the “World” to offer him the story, and the reader will need a vivid imagination to get an idea of my emotions when this friend exclaimed, “Why, that story has already been used by the ‘Journal’!

“That is impossible !” I exclaimed. He answered, “I have a copy of it upon my desk.” It was not until I was going on board the steamer that I got a copy of the “final extra” of the “New York Evening Journal,” the issue of Monday, December 29, 1913. At the top of the front page, in red letters more than one-half inch high, appeared the caption:

JOURNAL FINDS MISS BRANCH HERE

with two index hands to point out this wonderful news to the reader. A good portion of the remainder of the front page was occupied by an article with these headings:

HEART-WIFE IS IN NEW YORK

Found Here by Journal.

Miss Branch Traced to Well-Known Writer’s Home After Secret Flight.

Adelaide M. Branch, for three years the heart-wife of Melvin H. Couch, former District Attorney of Sullivan County, is today in New York City. She is secluded at the home of a well-known sociologist and writer who has interested himself in her case and has offered her a home, at least until she can make definite plans for the future.

Miss Branch was traced to her hiding place in this city by the “Evening Journal.” The former “love slave” of Couch told the sociologist that she wished to be absolutely quiet and undisturbed. So for the present it is not possible to give her address.

And so continued a long article, which contained practically everything of what I gave to Mr. Thorpe, sometimes even using the very phrases which I had used in the presence of my wife.

I will not trouble the reader with a description of the state of mind we were in when our steamer set out for Bermuda. I will simply give a brief summary of what else occurred in this incredible affair:

First, someone got, or pretended to get, from the hall-boy at the apartment where I had been staying, an elaborate and entirely fictitious account of how Miss Branch had arrived, and how she had swooned and my wife had caught her in her arms, and how some other people had come and carried her away in an automobile. This account was published in full.

Then the records of my telephone-calls were consulted, and every person whom I had called up in my last two days in the apartment was hounded. My poor mother was driven nearly to desperation. In our telephone-call list was found the name of Dr. Warbasse, who had taken Miss Branch away, and Dr. Warbasse later received a wireless message from Bermuda, as follows:

“Give Branch story to papers.”

Shortly afterward the doctor was called up by the “Evening Journal,” and was told that the “Journal” had received a wireless message from me, instructing them to call on him for information concerning Miss Branch. I quote from Dr. Warbasse’s letter to me:

I believed the only way they could have learned of my connection with the case was from you, and accordingly gave them a short statement of the facts, but withheld the location of Miss Branch. They published very distorted versions of what little I gave them. They were particularly solicitous for her whereabouts. A few days later I had another wireless from you, asking me to send you Branch’s address. By this time I had grown suspicious, and sent you my address instead. I am now wondering whether the wireless messages were from you or were newspaper fakery. If the latter is the case, it was well done, believe me, and does great credit to the unscrupulousness of the press.

Needless to say, I had sent no such message. What is more significant, I did not receive the message which Dr. Warbasse sent to me, giving me his address! Is the “Evening Journal” able to intercept cablegrams? I don’t know; but soon after my arrival in Bermuda I received a letter from my friend who conducts the school for young ladies, scolding me for the terrible trouble into which I had got her. The “Journal,” she said, had become convinced that Miss Branch was hidden in the school, and it was only by desperate efforts that she had kept this highly sensational rumor from going out to the world. I thought, of course, that I was to blame for my thoughtlessness in having given her telephone number to the “Evening Journal” on the eve of my departure from New York, and I wrote abjectly apologizing for this. What was my consternation to receive a letter assuring me that this was not what had angered her, but the fact that I had been so foolish as to send her a wireless message, instructing her to give the story of Miss Branch to the paper, and had wired the “Journal” to call upon her for the information!

Mr. Arthur Brisbane is the man whom I had always understood to be the editor in charge of the “Evening Journal.” I wrote him asking him to investigate this affair; and I sent a registered copy of the letter to Mr. Hearst, who, I assumed, would be jealous for the journalistic honor of his papers. I pointed out the fact that on the Monday afternoon in question every newspaper in New York had had the story that Miss Branch was going West to see a brother of hers. In all editions of the Evening Journal, except the final edition, the following statement had appeared:

Heart-wife flees to asylum. Miss Branch is in hiding in a sanitarium within ten miles of Monticello. As soon as she recovers her strength she will probably join her brother.

I said that I wished to know what Mr. Van Hamm had to say, as to how the Journal had got the information it published in its final edition. If it was an independent tip, who gave that tip? And if the telephone-call alleged to be from the Sheriff had come from any other paper than the “Journal,” why had not that paper used the story?

Mr. Brisbane replied that he was now in Chicago, and had no longer anything to do with the New York Evening Journal, but that the matter would undoubtedly be investigated by Mr. Hearst.

A friend of mine, an old newspaper man, wrote me a propos of this: “Don’t imagine for one minute that anything will be done about it; don’t imagine but that Van Hamm is Hearst. Hearst knows exactly what Van Hamm does, and if Van Hamm failed to do it, he would lose his job.” This sounded somewhat comical, but it seemed to be borne out by Mr. Hearst’s course. He chose to veil himself in Olympian silence. I wrote him a second courteous letter, to the effect that unless I heard from him and received some explanation, I would be compelled to assume that he intended to make the actions of his subordinates his own. He has not replied to that letter, so I presume that I am justified in the assumption. And this man wishes to be United States Senator from New York!

Several years ago he desired to be Governor, and there resulted such a tempest of public wrath, such a chorus of exposure and denunciation, that he was overwhelmed; if he had not had a very tough skin he would have fled from political life forever. Unquestionably a deal of this denunciation came from vested interests which he had frightened by his radicalism; but, on the other hand, it betrayed a note of personal loathing that was unmistakable. I marveled at it at the time; but now I think I understand it.

Several years ago he desired to be Governor, and there resulted such a tempest of public wrath, such a chorus of exposure and denunciation, that he was overwhelmed; if he had not had a very tough skin he would have fled from political life forever. Unquestionably a deal of this denunciation came from vested interests which he had frightened by his radicalism; but, on the other hand, it betrayed a note of personal loathing that was unmistakable. I marveled at it at the time; but now I think I understand it.

The story of Miss Branch is forgotten, but other stories are filling the Hearst papers day by day. Are they all got with the same disregard for every consideration of decency, for all the rules which control the dealings of civilized men with one another? Get clear the meaning of this story of mine—the reason for all this lying, sneaking, forging of cablegrams, bribing of hall-boys, violation of honor and good faith. Was it to get a story? No—the Journal had the story offered to it on a silver tray! The reason for all the knavery was to avoid the payment of three hundred dollars to a destitute and distracted woman—that, and that alone! And if such be Hearst’s attitude to his pocket-book, if such be the methods of his newspaper-machine where his pocket-book is concerned, there must be thousands and tens of thousands of people in New York — politicians, journalists, authors, businessmen—who have run into that machine as I did, and been knocked bruised and bloody into the ditch. When Mr. Hearst runs for office, all these men jump into the arena and get their revenge!

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

By subscribing, you will automatically receive the latest episodes downloaded to your computer or portable device. Select your preferred subscription method above.

To subscribe via a different application: Go to your favorite podcast application or news reader and enter this URL: https://clearwaterpress.com/byline/feed/podcast/