Disbanding the Confederate Army, part 1

Episode 31

The worst of the ordeal of these men, who had begun to disband in this haphazard way, was not getting home, it was what they found when they got there.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Email | TuneIn | RSS

Disbanding the Confederate Army, part 1

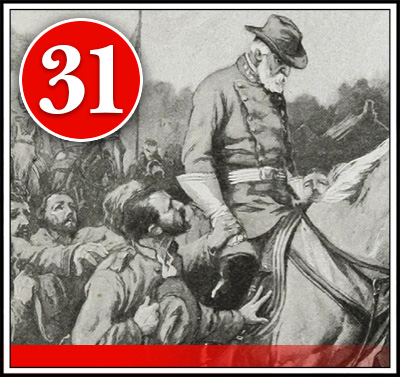

FOR a week the army of Northern Virginia had been fighting and retreating on parched corn, 57,000 men pursued by 125, 000. They had done their best, but now on April 9th, they were worn “to a frazzle,” all but 28,000 of their number had been captured, killed, or scattered, and on all sides they were surrounded by the Federals. It was not their hunger or weariness which occupied their thoughts at this moment, however; it was the dismal fact that off there a little distance their commander, General Lee, was surrendering them to General Grant.

Had he asked them to cut their way out of the circle which held them, battered and starved as they were, they would have tried to do it, but to submit, to surrender— that was harder. Yet when, a few hours later, the terms of the surrender arranged, the General, grave and pale, rode the length of their lines, they crowded about him as he went, their eyes wet with tears, their voices choked with sobs, struggling to kiss his hands, even to touch his horse—to show in some way that, bitter as their hearts were, there was nothing in them but love and honor for him.

The next day these men, who had fought from Bull Run to Petersburg, and won as brilliant victories as history records, marched up, stacked their muskets, signed a printed form of parole not to take arms again against the United States, and that alone in their pockets to face the world with, scattered north and south, east and west.

The news of Lee’s surrender spread slowly but steadily through the Confederacy. By the evening of the 10th it had reached a force of seven or eight thousand men near Christianburg. At first the officers tried to conceal it from the men, but it could not be hushed.

“Before we had concluded our brief conversation,” writes General Duke, one of the staff, “we knew from the hum and stir in the anxious, dark-browed crowds nearest us, from excitement which soon grew almost to tumult, that the terrible tidings had got abroad. That night no man slept. Strange as the declaration may sound now, there was not one of the six or seven thousand then gathered at Christianburg who had entertained the slightest thought that such an event could happen, and doubtless that feeling pervaded the ranks of the Confederacy.

During all the night officers and men were congregated in groups and crowds discussing the news. Great fires were lighted, every group had its orators who, succeeding each other, spoke continuously. Every conceivable suggestion was offered. Some advocated a guerrilla warfare; some proposed marching to the trans-Mississippi and thence to Mexico; the more practical and reasonable, of course, proposed that an effort to join General Johnston should immediately be made.”

Spreading southward, the news on the 12th reached Joe Johnston, whose army was in North Carolina, facing that of Sherman. Johnston knew only too well what Lee’s surrender meant for him, and on the 13th asked Sherman for a suspension of active operations. Two weeks later he surrendered his entire force. The effect of the news was the same on the only other Confederate army east of the Mississippi—that of Dick Taylor, which on May 4th surrendered to General Canby. The principal Confederate force west of the Mississippi was stationed in Texas. There was no telegraph beyond the boundary line at that date, only one railroad penetrated the State, and the harbors were all blockaded, so that it was late in April before the news came to Texas.

There came with it rumors that President Davis and his Cabinet and the armies of Johnston and Taylor were on their way to the trans-Mississippi region, and that there a new stand was to be taken and a new country opened. On this rumor such hopes were built that there was no thought of surrender.

“Stand by the ship, boys, as long as there is one plank upon another,” General Joe Shelby said on April 26th in his address to his troops.

“We are not whipped,” declared General Magruder on May 5th, “and no matter what may transpire, recollect we never will be whipped.” Mass-meetings of citizens and soldiers were held all over the State, and resolutions of resistance adopted.

But swift upon the report that Johnston and Taylor and Davis had escaped came reports of their surrender. As soon as this news was confirmed in Texas, there followed in the army what was long known as the break-up.” It was a widespread and immediate decamping of the soldiers with whatever army property they could get their hands on. Officers wakened in the morning to find that where they had had three companies at night they had one now. In squads, singly, or by twos, the soldiers started for home without as much as a word of farewell. It was a complete conviction that the game was up and they must shift for themselves which had taken hold of the Texas army, and to which only a minority were sufficiently superior to remain until their officers could give them proper discharge papers.

On May 26th a formal surrender took place. The commander-in-chief of the Confederate forces west of the Mississippi was General Kirby Smith. He was in Shreveport, Louisiana, when the ” break-up” began, but hastened to Texas, his idea being to concentrate the entire force under his command in order to obtain honorable terms or to continue the struggle. On May 30th, at Houston, he issued an address in which he declared that he had returned to find himself “a commander without an army, a general without troops.”

“You have made your choice,” he told the soldiers. ”It was unwise and unpatriotic, but it is final. You have voluntarily destroyed your organization, and thrown away all means of resistance.” Two days later he ratified the terms of surrender between Canby and Buckner, agreed to on May 26th.

Thus in six weeks an army scattered over a country nearly 2,000 miles in length and 1,000 in width—an army which had conducted a brave resistance for four years had crumbled into its original units. The great bulk of this army took the first step in their disbandment according to the rules laid down by their victors. It was only a small percentage which refused their compliance and decamped at the word of surrender, like the men referred to above by General Smith.

The men who left thus unceremoniously were of two classes: those who were sick of the whole business, and simply wanted to get home as quickly as possible, and those who were unwilling to give up fighting. The former was by far the larger class, but both classes contributed to the disorders which followed the surrender of General Lee. The Federals proposed that the entire Confederate force should take paroles and surrender their arms, and they attempted to force those who had decamped to do so.

For many weeks the forces left in the East occupied themselves in running down Confederates without paroles. Thus in the last of April Colonel H . B. Reed went up the Shenandoah Valley with a force and secured some 900 paroles. The official records of the period contain many accounts of scouts resulting in a few paroles and the discovery of small quantities of concealed arms.

In Texas, where the largest number of men had deserted, the Federal general in charge of the State sent out orders in June that all Confederates must report at certain points, bring in their muskets, and be paroled. Few ever obeyed the order, and the State was too large for the military authorities to enforce it. Gradually the attempt to secure complete paroles was abandoned as doing more harm than good.

The number of recalcitrants who proposed to carry on the war individually or collectively has been greatly exaggerated. The guerrilla warfare which followed the surrender of the forces was really unimportant, though it caused considerable uneasiness in the North. In the mountains of Virginia small bands took refuge for a time and made raids on the inhabitants.

In North Carolina, too, there was considerable complaint of marauding, but when the disturbers were run down they generally proved to be disorderly characters, stragglers from both armies, who had taken to robbery as a means of livelihood.

In the West the trouble from guerrillas was naturally longer continued than in the East. What it actually amounted to there one can best judge from the reports of the officers who were in charge of the districts.

Missouri was, after Texas, the longest in revolt, but even in May and June of ’65 there was no very serious resistance there, and the bands were not numerous— one of thirty-five was driven out from the headwaters of the Little Piney in May, a few of the men being killed, the rest escaping. The captain of a company sent to the Blackwater near Longwood, Missouri, to clear out the reported bushwhackers, reported that, after having scouted the country daily for miles around during nearly three weeks, he had run down three bushwhackers—who broke through the bush and made their escape. Five men were caught by United States troops at Valley Mines robbing a store on May 22d, and one man was killed.

In short, this guerrilla warfare when analyzed resolves itself chiefly into the marauding of irresponsible and desperate bands, composed of a few Confederates, a sprinkling of renegade Federals, and many desperadoes who had never worn a uniform. It continued with diminishing strength for several months. Indeed, it was not until April 2, 1866, that President Johnson issued a proclamation that war was legally terminated.

Even then Texas was omitted from the list of pacified States, and it was not until August 20, 1866, that Johnson issued a proclamation which included Texas, and which proclaimed “the insurrection is at an end,” and “peace, order, tranquillity, and civil authority now exist in and throughout the whole of the United States.” In March, 1867, Congress declared that the date of this second proclamation should be considered as the legal termination of the war. It is so considered in cases before the courts, in which such a date is necessary, as it has been more than once in settling pension claims.

But whether the disbanding soldiers complied with the Federal regulations or not, whether they took to the mountains and bayous or started on the nearest route to their homes, they were in a curious and perplexing position. They were literally men without a country. The government which had enlisted and supported them was dead, its officials were prisoners, its constitution void, its currency worthless.

At the outset a dreadful practical question faced them. How were they going to get to their former homes? They had no money. Whatever funds their generals had been able to get hold of had been divided among them, but it was the merest pittance. Johnston when he saw surrender was inevitable had secured money to pay his men and officers a dollar apiece. Lee’s men had received nothing. Dick Taylor’s had received nothing.

Penniless as they were, nothing but walking or working their way would have been left to the entire Confederate army if the Federals had not wisely and justly come to their relief. General Grant inaugurated this movement by allowing Lee’s men to keep their horses. He also allowed his own quartermasters to turn over to the Confederates whatever horses and mules they could spare. Johnston’s army fared a little better, for not only were they given their animals, but it was arranged that those who lived beyond the Mississippi should have transportation by water to some Southern port. The same arrangements were made for Taylor’s army.

With the signing of the paroles all organization ceased, and the men were expected to disperse. Those who had horses mounted them, and in twos and threes or half-dozens rode away. Sometimes a body of men, whose homes were far away, were kept together and marched under Federal directions to a convenient point, and a limited amount of transportation furnished to them which would bring them within easier distance of their journey’s end.

Often there were no horses or mules, no transportation, and the men were obliged to shift for themselves, with the result that thousands straggled across country afoot, often for hundreds of miles, trusting to the hospitality of the people for food.

“I am daily touched to the heart,” wrote a correspondent of the New York Tribune in May, ‘”by seeing these poor homesick boys and exhausted men wandering about in threadbare uniforms, with scanty outfit of slender haversack and blanketroll hung over their shoulders, seeking the nearest route home; they have a care-worn and anxious look, a played-out manner.”

The worst of the ordeal of these men, who had begun to disband in this haphazard way, was not getting home, it was what they found when they got there. The inventory of destruction in the South by the war is appalling. From the Potomac to the Rappahannock the country was cleaned of fences, of trees, of landmarks of every description. At Manassas, a town of forty or fifty houses before the war, there stood now forty or fifty chimneys. From the Rappahannock to Richmond all Eastern Virginia was a great and desolate battlefield, its only crop rusty canteens and moldy bread, knapsacks and exploded shells, and, thick as the grass in spring —Minié balls. Richmond after the havoc of a long siege had been swept by fire.

Across South Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama lay the path of devastation wrought by Sherman’s army. In the streets of Charles ton the grass was growing, while Summerville, its once favorite resort, from a prosperous town of 2,500 had been reduced to a hamlet of 200 half-starved souls. At Columbia, South Carolina, there was block upon block of dwellings, shops, and institutions of which nothing was left but jagged brick walls and slender, melancholy chimneys. Atlanta, Chattanooga, Vicksburg, Nashville, had been riddled by shell and turned topsy-turvy by hostile occupation.

For four years, only irregular crops had been put in, and though there was cotton left in the country, there was no way for its owners to secure it or dispose of it. Most of the great manufactories of the South were destroyed or shut down— the Tredegar Iron Works at Richmond, the salt works in the Valley of the Holston, the iron manufactories at Marion, the lead works of Wythe County.

Not only were fully two-thirds of all property destroyed and all industries at a stand-still, but those fundamental contrivances by which property is made productive and put into circulation were destroyed. Their labor system was wiped out by the emancipation of the slaves. The railroads were gone, tracks torn up, bridges destroyed, engines and cars worn out. Their ports had been long blockaded, and their shipping was destroyed. There was no postal system, and their money was useless, except as it could be disposed of to curiosity hunters.

It was through this desolation that the disbanding Confederates made their way to their homes. All of those who lived in the track of the armies were haunted, not only by the fear of finding their homes destroyed, but finding their families scattered. It had been necessary for women and children all over Eastern and Northern Virginia to fly from the country. Sherman had driven the entire population from Atlanta when he left the city for his march to the sea, not wishing to feed and guard them as would have been necessary. Everywhere the people had scattered at the coming of the soldiers, hundreds going to Texas, a few to Europe, many to Canada, thousands into the portions of the States outside of the track of battle. The returning soldiers frequently knew little or nothing of where their loved ones had gone, and had no idea of how they would reach them.

The personal experiences related by Mrs. C. D. Maclean, in the Southern Historical Society Papers, are typical of the condition in which numbers of women found themselves at the close of the war. Mrs. Maclean’s home was in Columbia, South Carolina, and she and her sister had been sent to the interior of North Carolina for safety. Here they were completely cut off, and it was not until May that she learned of Lee’s surrender.

Then one day two threadbare soldiers passing stopped for a drink. They told what had happened, and explained that they were bound for South Carolina to “bushwhack Yankees.” Eager as Mrs. Maclean was to get home now, it was not until midsummer that an opportunity came. Then a neighbor offered to take her to Greensboro, forty miles distant, in a dilapidated buggy drawn by a “spavined mule.”

At Greensboro she was able to take the remnant of a railroad which ran within a few miles of her home, and to finish her journey by stage-coach.” I approached Columbia from the north,” writes Mrs. Maclean, “over bleak bare, sandhills, and it was from the nearest of these that I first saw the ruined city spread out like a neglected kiln below. At the sight I burst into tears.”

Once back in their homes, the disbanding soldiers were met by the long series of difficult questions incident to the condition of the country, the first and most imperative of which was usually how to get bread for the coming year. As a rule there was nothing for them to do but take hold of the humblest tasks.

Take Richmond, for example. The town was in such condition that business could not be carried on. Its ruins had to be cleared away and the streets rebuilt. Nothing is finer than the way in which the men of the highest breeding and education went to pulling down walls, clearing brick, laying foundations. John S. Wise, in The End of an Era, says of the laborers he found filling the streets of Richmond in the month after the surrender:

“Many of them I knew well—men of as good social position as my own; soldiers come home and resolved not to be idle, but to work for an honest living in any way in which they could make it. Sitting in the sun with their trowels, jabbing away in awkward fashion at their new and unaccustomed tasks, covered with dust and plaster, they were the same bright, cheerful fellows who had learned to labor in that state of life to which it had pleased God to call them, just as they had been willing followers, in sunshine and in storm, of their beloved Lee. At night, with their day’s wages in their pockets, they would go home, change their clothing, take a bath, and associate with their families—not at all ashamed of their labors, but making a joke of their newly discovered method of earning a sustenance.”

Many of these people had property, to be sure, but it was impossible then to realize on it, even if they had wished to sacrifice it, nobody being willing to buy property which might be liable later to confiscation. There were hundreds, too, who owned valuable jewels, plate, pictures, or furniture which they would have disposed of if they had been able. One of the most pathetic editorials in the early numbers of the Richmond Whig is one headed: “A Pawnbroker Wanted,” explaining the need there was of such a dealer in the town.

In the country a livelihood was even more uncertain than in the towns. John Wright, now of the Department of the Interior, told the author:

“The crops of the country had been consumed by the people or had gone to support the army. … When the soldiers returned they found only ashes where their homes had been, their wives and children houseless, and stricken with poverty. The grand conduct of General Grant in allowing the soldiers of Lee to retain their horses served to mitigate the condition to some extent, as these soldiers used the horses in cultivating the land. This condition was almost universal. It is believed that in the history of the world no country was so entirely destroyed over so large a space as was the South. … I suppose it may be safely said that very little went to the aid of the men who returned from the war.”

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

By subscribing, you will automatically receive the latest episodes downloaded to your computer or portable device. Select your preferred subscription method above.

To subscribe via a different application: Go to your favorite podcast application or news reader and enter this URL: https://clearwaterpress.com/byline/feed/podcast/