To Be Treated as a Spy

Episode 5 •

To Be Treated as a Spy

• With four automatics rubbing against my ribs, I would not have lowered my arms for all the papers in the Bank of England.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Email | TuneIn | RSS

SHOW NOTES ____________

To Be Treated as a Spy

By Richard Harding Davis

1914

THIS story is a personal experience, but is told in spite of that fact, and because it illustrates a side of war that is unfamiliar. It is unfamiliar for the reason that it is seamy and uninviting. With bayonet charges, bugle-calls, and aviators it has nothing in common.

Espionage is that kind of warfare of which even when it succeeds no country boasts. It is military service an officer may not refuse but which few seek. Its reward is prompt promotion, and its punishment, in war-time, is swift and without honor. This story is intended to show how an army in the field must be on its guard against even a supposed spy and how it treats him.

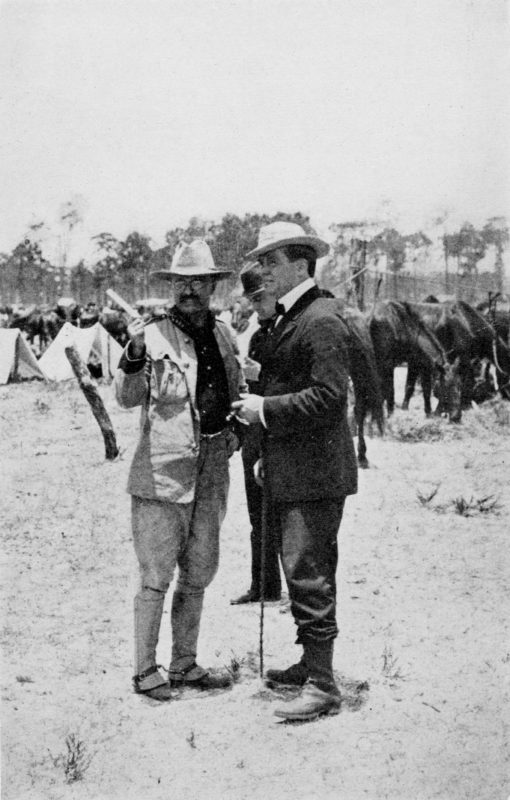

Richard Harding Davis with Teddy Roosevelt.

The war offices of France and Russia would not permit an American correspondent to accompany their armies; the English granted that privilege to but one correspondent, and that gentleman had been chosen. So I was without credentials. Belgium was willing to give me credentials, but on the day I was to receive them the government moved to Antwerp. Then the Germans entered Brussels, and as no one could foresee that Belgium would heroically continue fighting, on the chance the Germans would besiege Paris, I planned to go to that city. To be bombarded you do not need credentials.

For three days a steel-gray column of Germans had been sweeping through Brussels, and to meet them the English and French had crossed the border. It was falsely reported that already the English had reached Hal, a town only eleven miles from Brussels, that the night before there had been a fight at Hal, and that close behind the English were the French.

With Gerald Morgan, of the London Daily Telegraph, with whom I had been in other wars, I planned to drive to Hal and continue on foot into the arms of the French or English. We both were without credentials, but once with the Allies we believed we would not need them. It was the Germans we doubted. To satisfy them we had only a passport and a laisser passer issued by General von Jarotsky, the new German military governor of Brussels, and his chief of staff, Lieutenant Geyer. Mine stated that I represented the Wheeler Syndicate of American newspapers, the London Daily Chronicle, and this magazine, and that I could pass German military lines in Brussels and her environs. Morgan had a pass of the same sort.

The question to be determined was what were “environs” and how far do they extend? How far in safety would the word carry us forward ? On August 23 we set forth from Brussels in a taxi-cab to find out. At Hal, where we intended to abandon the cab and continue on foot, we found out. We were arrested by a smart and most intelligent looking officer, who rode up to the side of the taxi and pointed an automatic at us. We were innocently seated in a public cab, in a street crowded with civilians and the passing column of soldiers, and why any one should think he needed a gun only the German mind can explain. Later, I found that all German officers introduced themselves and made requests gun in hand. Whether it was because from every one they believed themselves in danger or because they simply did not know any better, I still am unable to decide. With no other army have I seen an officer threaten with a pistol an unarmed civilian. Were an American or English officer to act in such a fashion he might escape looking like a fool, he certainly would feel like one.

Four soldiers climbed into our cab and drove with us until the street grew too narrow both for their regiment and our taxi, when they chose the regiment and disappeared. We paid off the cabman and followed them. To reach the front there was no other way, and the very openness with which we trailed along beside their army, very much like small boys following a circus procession, seemed to us to show how innocent was our intent. The column stretched for fifty miles. Where it was going we did not know, but we argued if it kept on going and we kept on with it, eventually we must stumble upon a battle. The story that at Hal there had been a fight was evidently untrue; and the manner in which the column was advancing showed it was not expecting one. At noon it halted, and Morgan decided that the limits of our “environs” had been reached.

“If we go any farther,” he argued, “the next officer who reads our papers will order us back to Brussels under arrest, and we will lose our laisser passer. Along this road there is no chance of seeing anything, I prefer to keep my pass and use it in ‘environs’ where there is fighting.” So he returned to Brussels. I thought he was most wise, and I wanted to return with him. But I did not want to go back only because I knew it was the right thing to do, but to be ordered back so that I could explain to my newspapers that I returned because Colonel This or General That sent me back. It was a form of vanity for which I was properly punished.

That Morgan was right was demonstrated as soon as he left me. I was seated against a tree by the side of the road eating a sandwich, an occupation which seems almost idyllic in its innocence but which could not deceive the Germans. In me they saw the hated Spy, and from behind me, across a ploughed field, four of them, each with an automatic, made me prisoner. One of them, the enthusiast, pushed his gun deep into my stomach. With the sandwich still in my hand, I held up my arms high and asked who spoke English. It turned out that the enthusiast spoke that language, and I suggested he did not need so many guns and that he could find my papers in my inside pocket. With four automatics rubbing against my ribs, I would not have lowered my arms for all the papers in the Bank of England.

They took me to a cafe, where their colonel had just finished lunch and was in a most genial humor. First he gave the enthusiast a drink as a reward for arresting me, and then, impartially, gave me one for being arrested. He wrote on my passport that I could go to Enghien, which was two miles distant. That pass enabled me to proceed unmolested for nearly two hundred yards. I was then again arrested and taken before another group of officers. This time they searched my knapsack and wanted to requisition my maps, but one of them pointed out they were only automobile maps and, as compared to their own, of no value. They permitted me to proceed. I went to Enghien, intending to spend the night and on the morning continue. I could not see why I might not be able to go on indefinitely. As yet no one who had held me up had suggested I should turn back, and as long as I was willing to be arrested it seemed as though I might accompany the German army even to the gates of Paris. But my reception in Enghien should have warned me to get back to Brussels. The Germans, thinking I was an English spy, scowled at me; and the Belgians, thinking the same thing, winked at me; and the landlord of the only hotel said I was “suspect” and would not give me a bed. But I sought out the burgomaster, a most charming man named Delano, and he wrote out a pass permitting me to sleep one night in Enghien.

“You really do not need this,” he said; “as an American you are free to stay here as long as you wish.” Then he, too, winked.

“But I am an American,” I protested.

“But certainly,” he said gravely, and again he winked. It was then I should have started back to Brussels. Instead, I sat on a moss-covered, arched stone bridge that binds the town together, and until night fell watched the gray tidal waves rush up and across it, stamping, tripping, stumbling, beating the broad, clean stones with thousands of iron heels, steel hoofs, steel chains, and steel-rimmed wheels. You hated it, and yet could not keep away. The Belgians of Enghien hated it, and they could not keep away. Like a great river in flood, bearing with it destruction and death, you feared and loathed it, and yet it fascinated you and pulled you to the brink. All through the night, as already for three nights and three days at Brussels, I had heard it; it rumbled and growled, rushing forward without pause or breath, with inhuman, pitiless persistence. At daybreak I sat on the edge of the bed and wondered whether to go on or turn back. I still wanted someone in authority, higher than myself, to order me back. So, at six, riding for a fall, I went along the road to Soignes. The gray tidal wave was still roaring past. It was pressing forward with greater speed, but in nothing else did it differ from the tidal wave that had swept through Brussels.

There was a group of officers seated by the road, and as I passed I wished them good-morning and they said good morning in return. I had gone a hundred feet when one of them galloped after me and asked to look at my papers. With relief I gave them to him. I was sure now I would be told to return to Brussels. I calculated if at Hal I had luck in finding a taxi-cab, by lunch-time I would be in the Palace Hotel.

“I think,” said the officer, “you had better see our general. He is ahead of us.”

I thought he meant a few hundred yards ahead, and to be ordered back by a general seemed more convincing than to be returned by a mere captain. So I started to walk on beside the mounted officers. This, as it seemed to presume equality with them, scandalized them greatly, and I was ordered into the ranks. But the one who had arrested me thought I was entitled to a higher rating and placed me with the color-guard, who objected to my presence so violently that a long discussion followed, which ended with my being ranked below a second lieutenant and above a sergeant. Between one of each of these I was definitely placed and for five hours I remained definitely placed. We advanced with a rush that showed me I had surprised a surprise movement. The fact was of interest not because I had discovered one of their secrets, but because to keep up with the column I was forced for five hours to move at what was a steady trot, a ” double-quick.” Had I not been in good shape I could not have kept up. As it was, at the end of the five hours I had lost fifteen pounds, which did not help me, as during the same time the knapsack had taken on a hundred.

For two days the men in the ranks had been rushed forward at this unnatural gait and were moving like automatons. Many of them fell by the wayside, but they were not permitted to lie there. Instead of summoning the ambulance, they were lifted to their feet and flung back into the ranks. Many of them were moving in their sleep, in that partly comatose state in which you have seen men during the last hours of a six days’ walking match. Their rules, so the sergeant said, were to halt every hour and then for ten minutes’ rest. But that rule is probably only for route marching. On account of the speed with which the surprise movement was made, our halts were more frequent, and so exhausted were the men that when these “thank you, ma’ams” arrived, instead of standing at ease and adjusting their accoutrements, they dropped to the stones. I do not mean that some sat down; I mean that the whole column lay flat in the road. The officers also, those that were not mounted, would tumble on the grass or into the wheat-field and lie on their backs, their arms flung out like dead men. To the fact that they were lying on their field-glasses, holsters, swords, and water bottles they appeared indifferent. At the rate the column moved it would have covered thirty miles each day. It was these forced marches that later brought Von Kluck’s army to the right wing of the Allies.

While we were pushing forward we passed a wrecked British air-ship, around which were gathered a group of staff-officers. My papers were given to one of them, but our column did not halt and I was not allowed to speak. A few minutes later they passed in their automobiles on their way to the front; and my papers went with them. Already I was miles beyond the environs, and with each step away from Brussels my pass was becoming less of a safeguard than a menace. For it showed what restrictions General Jarotsky had placed on my movements, and my presence so far out of bounds proved I had disregarded them. But still I did not suppose that in returning to Brussels there would be any difficulty. I was chiefly concerned with the thought that the length of the return march was rapidly increasing and with the fact that one of my shoes, a faithful friend in other campaigns, had turned traitor and was cutting my foot in half. I had started with the column at seven o’clock, and at noon an automobile, with flags flying and the black eagle of the staff enameled on the door, came speeding back from the front. In it was a very blond and distinguished looking officer of high rank and many decorations. He used a single eye-glass, and his politeness and his English were faultless. He invited me to accompany him to the general staff.

That was the first intimation I had that I was in danger. I saw they were giving me far too much attention. I began instantly to work to set myself free, and there was not a minute for the next twenty-four hours that I was not working. Before I stepped into the car I had decided upon my line of defence. I would pretend to be entirely unconscious that I had in any way laid myself open to suspicion; that I had erred through pure stupidity and that I was where I was solely because I was a damn fool. I began to act like a damn fool. Effusively I expressed my regret at putting the general staff to inconvenience.

“It was really too stupid of me,” I said.

“I cannot forgive myself. I should not have come so far without asking Jarotsky for proper papers. I am extremely sorry I have given you this trouble. I would like to see the general and assure him I will return at once to Brussels.” I ignored the fact that I was being taken to the general at the rate of sixty miles an hour. The blond officer smiled uneasily and with his single glass studied the sky. When we reached the staff he escaped from me with the alacrity of one released from a disagreeable and humiliating duty. The staff were at luncheon, seated in their luxurious motor-cars, or on the grass by the side of the road. On the other side of the road the column of dust-covered gray ghosts were being rushed past us. The staff in dress uniforms, flowing cloaks, and gloves belonged to a different race. They knew that. Among themselves they were like priests breathing incense. Whenever one of them spoke to another they saluted, their heels clicked, their bodies bent at the belt line.

One of them came to where, in the middle of the road, I was stranded and trying not to feel as lonely as I looked. He was much younger than myself and dark and handsome. His face was smooth-shaven, his figure tall, lithe, and alert. He wore a uniform of light blue and silver, and high boots of patent leather. His waist was like a girl’s, and, as though to show how supple he was, he kept continually bowing and shrugging his shoulders and in elegant protest gesticulating with his gloved hands. He should have been a moving-picture actor. He reminded me of Anthony Hope’s fascinating but wicked Rupert of Hentzau. He certainly was wicked, and I got to hate him as I never imagined it possible to hate anybody. He had been told to dispose of my case, and he delighted in it as a cat enjoys playing with a mouse.

“You are an English officer out of uniform,” he began. “You have been taken inside our lines.” He pointed his forefinger at my stomach and wiggled his thumb. “And you know what that means!”

I saw playing the damn fool with him would be waste of time.

“I followed your army,” I told him, “because it’s my business to follow armies and because yours is the best-looking army I ever saw.” He made me one of his mocking bows.

“We thank you,” he said, grinning. “But you have seen too much.”

“I haven’t seen anything,” I said, “that everybody in Brussels hasn’t seen for three days.”

He shook his head reproachfully and with a gesture signified the group of officers.

“You have seen enough in this road,” he said, “to justify us in shooting you now.”

The sense of drama told him it was a good exit line, and he returned to the group of officers. I now saw what had happened. I had taken the wrong road. The names on the signpost at the edge of the town had been painted out, and that instead of taking the road to Soignes I was on the road to Ath. What I had seen, therefore, was an army corps making a turning movement intended to catch the English on their right and double them up upon their centre. The success of this manoeuvre depended upon the speed with which it was executed and upon its being a complete surprise. As later in the day I learned, the Germans thought I was an English officer who had followed them from Brussels and who was trying to slip past them and warn his countrymen. What Rupert of Hentzau meant by what I had seen in the road was that, having seen the Count de Schwerin, who commanded the Seventh Division in the road to Ath, I must necessarily know that the army corps to which he was attached had separated from the main army of Von Kluck, and that, in going so far south at such speed, it was bent upon an attack on the English flank. All of which at the time I did not know and did not want to know. All I wanted was to prove I was not an English officer, but an American correspondent who by accident had stumbled upon their secret. To convince them of that, strangely enough, was difficult.

When Rupert of Hentzau returned, the other officers were with him, and, fortunately for me, they spoke or understood English. For the rest of the day what followed was like a legal argument. It was as cold-blooded as a game of bridge. Rupert of Hentzau wanted an English spy shot for his supper; just as he might have desired a grilled bone. He showed no personal animus, and, I must say for him, that he conducted the case for the prosecution without heat or anger. He mocked me, grilled and taunted me, but he was always charmingly polite.

The points he made against me were that my German pass was signed neither by General Jarotsky nor by Lieutenant Geyer, but only stamped, and that any rubber stamp could be forged; that my American passport had not been issued at Washington, but in London, where an Englishman might have imposed upon our embassy; and that in the photograph pasted on the passport I was wearing the uniform of a British officer.

I explained that the photograph was taken eight years ago, and that the uniform was one I had seen on the west coast of Africa worn by the West African Field Force. Because it was unlike any known military uniform, and as cool and comfortable as a golf-jacket, I had had it copied. But since that time it had been adopted by the English Brigade of Guards and the Territorials. I knew it sounded like fiction; but it was quite true.

Rupert of Hentzau smiled delightedly. “Do you expect us to believe that?” he protested.

“Listen,” I said. “If you could invent an explanation for that uniform as quickly as I told you that one, standing in a road with eight officers trying to shoot you, you would be the greatest general in Germany.”

That made the others laugh; and Rupert retorted: “Very well, then, we will concede that the entire British army has changed its uniform to suit your photograph. But if you are not an officer, why, in the photograph, are you wearing war ribbons?”

I said the war ribbons were in my favor, and I pointed out that no officer of any one country could have been in the different campaigns for which the ribbons were issued.

“They prove,” I argued, “that I am a correspondent, for only a correspondent could have been in wars in which his own country was not engaged.”

I thought I had scored; but Rupert instantly turned my own witness against me.

“Or a military attache,” he said. At that they all smiled and nodded knowingly.

He followed this up by saying, accusingly, that the hat and clothes I was then wearing were English. The clothes were English, but I knew he did not know that, and was only guessing; and there were no marks on them. About my hat I was not certain. It was a felt Alpine hat, and whether I had bought it in London or New York I could not remember. Whether it was evidence for or against I could not be sure. So I took it off and began to fan myself with it, hoping to get a look at the name of the maker. But with the eyes of the young prosecuting attorney fixed upon me, I did not dare take a chance. Then, to aid me, a German aeroplane passed overhead and those who were giving me the third degree looked up. I stopped fanning myself and cast a swift glance inside the hat. To my intense satisfaction I read, stamped on the leather lining: “Knox, New York.” I put the hat back on my head and a few minutes later pulled it off and said: “Now, for instance, my hat. If I were an Englishman, would I cross the ocean to New York to buy a hat?”

It was all like that. They would move away and whisper together, and I would try to guess what questions they were preparing. I had to arrange my defence without knowing in what way they would try to trip me, and I had to think faster than I ever have thought before. I had no more time to be scared, or to regret my past sins, than has a man in a quicksand. So far as I could make out, they were divided in opinion concerning me. Rupert of Hentzau, who was the adjutant or the chief of staff, had only one simple thought, which was to shoot me. Others considered me a damn fool; I could hear them laughing and saying: “Er ist ein dummer Mensch.” And others thought that whether I was a fool or not, or an American or an Englishman, was not the question; I had seen too much and should be put away. I felt if, instead of having Rupert act as my interpreter, I could personally speak to the general I might talk my way out of it, but Rupert assured me that to set me free the Count de Schwerin lacked authority, and that my papers, which were all against me, must be submitted to the general of the army corps, and we would not reach him until midnight.

“And then!—” he would exclaim, and he would repeat his pantomime of pointing his forefinger at my stomach and wiggling his thumb.

Meanwhile they were taking me farther away from Brussels and the “environs.”

“When you picked me up,” I said, “I was inside the environs, but by the time I reach ‘the’ general he will see only that I am fifty miles beyond where I am permitted to be. And who is going to tell him it was you brought me there? You won’t!”

Rupert of Hentzau only smiled like the cat that has just swallowed the canary.

He put me in another automobile and they whisked me off, always going farther from Brussels, to Ath and then to a little town five miles south. Here they stopped at a house the staff occupied, and, leading me to the second floor, put me in an empty room that seemed built for their purpose. It had a stone floor and whitewashed walls and a window so high that even when standing you could see only the roof of another house and a weather-vane. They threw two bundles of wheat on the floor and put a sentry at the door with orders to keep it open. He was a wild man, and thought I was, and every time I moved his automatic moved with me. It was as though he were following me with a spot-light. My foot was badly cut across the instep and I was altogether forlorn and disreputable. So, in order to look less like a tramp when I met the general, I bound up the foot, and, always with one eye on the sentry, and moving very slowly, shaved and put on dry things. From the interest the sentry showed it seemed evident he never had taken a bath himself, nor had seen any one else take one, and he was not quite easy in his mind that he ought to allow it. He seemed to consider it a kind of suicide. I kept on thinking out plans, and when an officer appeared I had one to submit. I offered to give the money I had with me to any one who would motor back to Brussels and take a note to the American minister, Brand Whitlock. My proposition was that if in five hours, or by seven o’clock, he did not arrive in his automobile and assure them that what I said about myself was true, they need not wait until midnight, but could shoot me then.

“If I am willing to take such a chance,” I pointed out, “I must be a friend of Mr. Whitlock. If he repudiates me, it will be evident I have deceived you, and you will be perfectly justified in carrying out your plan.” I had a note to Whitlock already written. It was composed entirely with the idea that they would read it, and it was much more intimate than my very brief acquaintance with that gentleman justified. But from what I have seen and heard of the ex-mayor of Toledo I felt he would stand for it.

The note read:

DEAR BRAND: I am detained in a house with a garden where the railroad passes through the village of Ligne. Please come quick, or send some one in the legation automobile.

RICHARD.

The officer to whom I gave this was Major Alfred Wurth, a reservist from Bernburg, on the Saale River. I liked him from the first because after we had exchanged a few words he exclaimed incredulously: “What nonsense! Anyone could tell by your accent that you are an American.” He explained that when at the university, in the same pension with him were three Americans.

“The staff are making a mistake,” he said earnestly. “They will regret it.”

I told him that I not only did not want them to regret it, but I did not want them to make it, and I begged him to assure the staff that I was an American. I suggested also that he tell them if anything happened to me there were other Americans who would at once declare war on Germany. The number of these other Americans I overestimated by about ninety millions, but it was no time to consider details.

He asked if the staff might read the letter to the American minister, and, though I hated to deceive him, I pretended to consider this.

“I don’t remember just what I wrote,” I said, and, to make sure they would read it, I tore open the envelope and pretended to reread the letter.

“I will see what I can do,” said Major Wurth; “meanwhile, do not be discouraged. Maybe it will come out all right for you.”

After he left me the Belgian gentleman who owned the house and his cook brought me some food. Then Major Wurth returned and said the staff could not spare any one to go to Brussels, but that my note had been forwarded to the general. That was as much as I had hoped for. It was intended only as a “stay of proceedings.” But the manner of the major was not reassuring. He kept telling me that he thought they would set me free, but even as he spoke tears would come to his eyes and roll slowly down his cheeks. It was most disconcerting. After a while it grew dark and he brought me a candle and left me, taking with him, much to my relief, the sentry and his automatic. This gave me since my arrest my first moment alone, and to find anything that might further incriminate or help me, I used it in going rapidly through my knapsack and pockets. My note-book was entirely favorable. In it there was no word that any German could censor. My only other paper was a letter, of which all day I had been conscious. It was one of introduction from Colonel Theodore Roosevelt to President Poincare, and whether the Germans would consider it a clean bill of health or a death-warrant I could not make up my mind. Half a dozen times I had been on the point of saying: “Here is a letter from the man your Kaiser delighted to honor, the only civilian who ever reviewed the German army, a former President of the United States.”

But I could hear Rupert of Hentzau replying: “Yes, and it is recommending you to our enemy, the President of France!”

I knew that Colonel Roosevelt would have written a letter to the German Emperor as impartially as to M. Poincare, but I knew also that Rupert of Hentzau would not believe that. So I decided to keep the letter back until the last moment. If it was going to help me, it still would be effective; if it went against me, I would be just as dead.

As it grew later I persuaded myself they did not mean to act until morning, and I stretched out on the straw and tried to sleep. At midnight I was startled by the light of an electric torch. It was strapped to the chest of an officer, who ordered me to get up and come with him. He spoke only German, and he seemed very angry. We got into another motor-car and in silence drove north down a country road to a great chateau that stood in a magnificent park. Something had gone wrong with the lights of the chateau, and its hall was lit only by candles that showed soldiers sleeping like dead men on bundles of wheat and others leaping up and down the marble stairs. They put me in a huge armchair of silk and gilt, with two of the gray ghosts to guard me, and from the hall I could see a long table on which were candles and many maps and half-empty bottles of champagne. Around the table, standing or seated, and leaning across the maps, were staff-officers in brilliant uniforms. They were much older men and of higher rank than any I had yet seen. They were eating, drinking, gesticulating. In spite of the tumult, some in utter weariness were asleep. Apparently, I had reached the headquarters of the mysterious general. I had arrived at what, for a suspected spy, was an inopportune moment. The Germans themselves had been surprised, or somewhere south of us had met with a reverse, and the air was vibrating with excitement and something very like panic. Outside, at great speed and with sirens shrieking, automobiles were arriving, and I could hear the officers shouting, “Die Englischen kommen!”

When the door from the drawing-room opened and Rupert of Hentzau appeared, I was almost glad to see him.

Whenever he spoke to me he always began or ended his sentence with “Mr. Davis.” He gave it an emphasis and meaning which was intended to show that he knew it was not my name. I would not have thought it possible to put so much insolence into two innocent words. It was as though he said, “Mr. Davis, alias Jimmy Valentine.” He certainly would have made a great actor.

“Mr. Davis,” he said, “you are free.” He did not look as disappointed as I knew he would feel if I were free, so I waited for what was to follow.

“You are free,” he said, “under certain conditions.” Rupert of Hentzau gave me a pass that, literally translated, reads:

“The American reporter Davis must at once return to Brussels via Ath, Enghien, Hal, and report to the government at the latest on August 26th. If he is met on any other road before the 26th of August, he will be handled as a spy. Automobiles returning to Brussels, if they can unite it with their duty, can carry him. CHIEF OF GENERAL STAFF. VON GREGOR, Lieutenant-Colonel.”

Fearing my military education was not sufficient to enable me to appreciate this, Rupert stuck his forefinger in my stomach and repeated cheerfully: “And you know what that means. And you will start,” he added, with a most charming smile, “in three hours.”

“At three in the morning!” I cried. “You might as well take me out and shoot me now!”

“You will start in three hours,” he repeated.

“A man wandering around at that hour,” I protested, “wouldn’t live five minutes. It can’t be done. You couldn’t do it.”

He continued to grin. I knew perfectly well the general had given no such order, and that it was a cat-and-mouse act of Rupert’s own invention, and he knew I knew it. But he repeated: “You will start in three hours, Mr. Davis.”

I said: ” I am going to write about this, and I would like you to read what I write. What is your name?”

He said: “I am the Baron von” — it sounded like “Hossfer”—and, in any case, to that name, care of General de Schwerin of the Seventh Division, I shall mail this magazine. I hope the Allies do not kill Rupert of Hentzau before he reads it! After that! He would have made a great actor.

They put me in the automobile and drove me back to the impromptu cell. But now it did not seem like a cell. Since I had last occupied it my chances had so improved that returning to the candle on the floor and the bundles of wheat was like coming home. Though I did not believe Rupert had any authority to order me into the night at the darkest hour of the twenty-four, I was taking no chances. My nerve was not in a sufficiently robust state for me to disobey any German. So, lest I should over-sleep, until three o’clock I paced the cell, and then, with all the terrors of a burglar, tiptoed down the stairs. There was no light, and the house was wrapped in silence. Earlier there had been everywhere sentries, and, not daring to breathe, I waited for one of them to challenge, but, except for the creaking of the stairs and of my ankle-bones, which seemed to explode like firecrackers, there was not a sound. I was afraid, and wished myself safely back in my cell, but I was more afraid of Rupert, and I kept on feeling my way until I had reached the garden. There some one spoke to me in French, and I found my host.

“The animals have gone,” he said; “all of them. I will give you a bed now, and when it is light you shall have breakfast.” I told him my orders were to leave his house at three.

“But it is murder!” he said. With these cheering words in my ears, I thanked him, and he bid me bon chance.

In my left hand I placed the pass, folded so that the red seal of the general staff would show, and a match-box. In the other hand I held ready a couple of matches. Each time a sentry challenged I struck the matches on the box and held them in front of the red seal. The instant the matches flashed it was a hundred to one that the man would shoot, but I could not speak German, and there was no other way to make him understand. They were either too surprised or too sleepy to fire, for each of them let me pass. But after I had made a mark of myself three times I lost my nerve and sought cover behind a haystack. I lay there until there was light enough to distinguish trees and telegraph poles, and then walked on to Ath. After that, when they stopped me, if they could not read, the red seal satisfied them; if they were officers and could read, they cursed me with strange, unclean oaths, and ordered me, in the German equivalent, to beat it. It was a delightful walk. I had had no sleep the night before and had eaten nothing, and, though I had cut away most of my shoe, I could hardly touch my foot to the road. Whenever in the villages I tried to bribe any one to carry my knapsack or to give me food, the peasants ran from me. They thought I was a German and talked Flemish, not French. I was more afraid of them and their shotguns than of the Germans, and I never entered a village unless German soldiers were entering or leaving it. And the Germans gave me no reason to feel free from care. Every time they read my pass they were inclined to try me all over again, and twice searched my knapsack. After that happened the second time I guessed my letter to the President of France might prove a menace, and, tearing it into little pieces, dropped it over a bridge, and with regret watched that historical document from the ex-President of one republic to the President of another float down toward the sea.

By noon I decided I would not be able to make the distance. For twenty-four hours I had been without sleep or food, and I had been put through an unceasing third degree, and I was nearly out. Added to that, the chance of my losing the road was excellent; and if I lost the road the first German who read my pass was ordered by it to shoot me. So I decided to give myself up to the occupants of the next German car going toward Brussels and ask them to carry me there under arrest. I waited until an automobile approached, and then stood in front of it and held up my pass and pointed to the red seal. The car stopped, and the soldiers in front and the officer in the rear seat gazed at me in indignant amazement. The officer was a general, old and kindly looking, and, by the grace of Heaven, as slow-witted as he was kind. He spoke no English, and his French was as bad as mine, and in consequence he had no idea of what I was saying except that I had orders from the general staff to proceed at once to Brussels. I made a mystery of the pass, saying it was very confidential, but the red seal satisfied him. He bade me courteously to take the seat at his side, and with intense satisfaction I heard him command his orderly to get down and fetch my knapsack. The general was going, he said, only so far as Hal, but that far he would carry me. Hal was the last town named in my pass, and from Brussels only eleven miles distant. According to the schedule I had laid out for myself, I had not hoped to reach it by walking until the next day, but at the rate the car had approached I saw I would be there within two hours.

My feelings when I sank back upon the cushions of that car and stretched out my weary legs and the wind whistled around us are too sacred for cold print. It was a situation I would not have used in fiction. I was a condemned spy, with the hand of every German properly against me, and yet under the protection of a German general, and in luxurious ease, I was escaping from them at forty miles an hour. I had but one regret. I wanted Rupert of Hentzau to see me. At Hal my luck still held. The steps of the Hotel de Ville were crowded with generals. I thought never in the world could there be so many generals, so many flowing cloaks and spiked helmets. I was afraid of them. I was afraid that when my general abandoned me the others might not prove so slow-witted or so kind. My general also seemed to regard them with disfavor. He exclaimed impatiently. Apparently, to force his way through them, to cool his heels in an anteroom, did not appeal. It was long past his luncheon hour and the restaurant of the Palace Hotel called him. He gave a sharp order to the chauffeur.

“I go on to Brussels,” he said. “Desire you to accompany me?” I did not know how to ask him in French not to make me laugh. I saw the great Palace of Justice that towers above the city with the same emotions that one beholds the Statue of Liberty, but not until we had reached the inner boulevards did I feel safe. There I bade my friend a grateful but hasty adieu, and in a taxi-cab, unwashed and unbrushed, I drove straight to the American legation. To Mr. Whitlock I told this story, and with one hand that gentleman reached for his hat and with the other for his stick. In the automobile of the legation we raced to the Hotel de Ville. There Mr. Whitlock, as the moving-picture people say, “registered ” indignation. Mr. Davis was present, he made it understood, not as a ticket-of-leave man, and because he had been ordered to report, but in spite of that fact. He was there as the friend of the American minister, and the word “Spion” must be removed from his papers.

And so, on the pass that Rupert gave me, below where he had written that I was to be treated as a spy, they wrote I was “not at all,” “gar nicht,” to be treated as a spy, and that I was well known to the American minister, and to that they affixed the official seal.*

That ended it, leaving me with one valuable possession. It is this: should any one suggest that 1 am a spy, or that I am not a friend of Brand Whitlock, I have the testimony of the Imperial German Government to the contrary.

•Literal translation of vise on the pass: BRUSSELS, August 25, 1914. Herr Davis was on the 25th of August at the headquarters of the German Government accompanied by the American minister and is not at all to be treated as a spy. He is highly recommended by the American minister and is well known in America. ALBERT BOVEY, Translator to Major- General Jaroisky.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

By subscribing, you will automatically receive the latest episodes downloaded to your computer or portable device. Select your preferred subscription method above.

To subscribe via a different application: Go to your favorite podcast application or news reader and enter this URL: https://clearwaterpress.com/byline/feed/podcast/