When I Went Home

Episode 12 •

When I Went Home

• I went back to the old home, to Denmark and to my mother; because I just couldn’t stay away any longer.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Email | TuneIn | RSS

SHOW NOTES ____________

When I Went Home

(Excerpted from chapters 15 & 16)

By Jacob Riis

I went back to the old home, to Denmark and to my mother; because I just couldn’t stay away any longer.

We had wandered through Holland, counting the windmills. We had argued with the keeper of the Prinzenhof in Delft that William the Silent could not possibly have been murdered as he said he was—that he must have come down the stairs and not gone across the hall when the assassin shot him, as any New York police reporter could tell from the bullet-hole that is yet in the wall—and thereby wounding his patriotic pride so deeply that an extra fee was required to soothe it. I caught him looking after us as we went down the street and shaking his head at those “wild Americans” who accounted nothing holy, not even the official record of murder done while their ancestors were yet savages roaming the plains.

We had laughed at the coal-heavers on the frontier carrying coal in baskets up a ladder to the waiting engine and emptying it into the fender. And now I was nearing the land where once more I should see old Dannebrog, the flag that fell from heaven with victory to the hard-pressed Danes. Literally out of the sky it fell in their sight, the historic fact being apparently that the Pope had sent a silken banner with the device of a white cross in red, and at the right moment, the priest threw it down from a cliff into the thick of the battle and turned its tide. Ever after, it was the flag of the Danes, and their German foes had reason to hate it. Here in Slesvig, through which I was traveling, to display it was good cause for banishment. But over yonder, behind the black post, it was waiting, and my heart leaped to meet it.

Have I not felt the thrill, when wandering abroad, at the sight of the stars and stripes suddenly unfolding, the flag of my home, of my manhood’s years and of my pride? Happy he who has a flag to love. Twice blest he who has two, and such two.

With the panorama of green meadows, of placid rivers, and of long-legged storks passing by our car-window, I can stop to tell you how this pride in the flag of my fathers once betrayed me into the hands of the Philistines. It was in London, during the wedding of the Duke of York. The king and queen of Denmark were in town, and wherever one went was the Danish flag hung out in their honor. Riding under one on top of a Holborn bus, I asked a cockney in the seat next to mine what flag it was. I wanted to hear him praise it, that was why I pretended not to know. He surveyed it with the calm assurance of his kind, and made reply:—

“That, ah, yes! It is the sign of St. John’s hambulance corps, the haccident flag, don’t you know,” and he pointed to an ambulance officer just passing with the cross device on his arm. The Dannebrog the “haccident flag”!

What did I do? What would you have done? I just fumed and suppressed as well as I could a desire to pitch that cockney into the crowds below, with his pipe and his miserable ignorance.

But there is the hoary tower of the old Domkirke in which I was baptized and confirmed and married, rising out of the broad fields, and all the familiar landmarks rushing by, and now the train is slowing up for the station, and a chorus of voices shout out the name of the wanderer. There is mother in the throng with the glad tears streaming down her dear old face, and half the town come out to see her bring home her boy, every one of them sharing her joy, to the very letter-carrier who brought her his letters these many years and has grown fairly to be a member of the family in the doing of it. At last the waiting is over, and her faith justified. Dear old mother! Gray-haired I return, sadly scotched in many a conflict with the world, yet ever thy boy, thy home mine. Heaven is nearer to us than we often dream on earth.

How shall I tell you of the old town by the North Sea that was the home of the Danish kings in the days when kings led their armies afield and held their crowns by the strength of their grip? Shall I paint to you the queer, crooked streets with their cobblestone pavements and tile-roofed houses where the swallow builds in the hall and the stork on the ridge-pole, witness both that peace dwells within?

Will you wander with me through the fields where the blue-fringed gentian blooms with the pink bell-heather, and the bridal torch nods from the brook-side?

Flat and uninteresting? Yes, if you will. If one sees only the fields. My children saw them and longed back to the hills of Long Island; and in their cold looks I felt the tugging of the chain which he must bear through life who exiled himself from the land of his birth. I played in these fields when I was a boy. I fished in these streams and built fires on their banks in spring to roast potatoes in, the like of which I have never tasted since. Here I lay dreaming of the great and beautiful world without, watching the skylark soar ever higher with its song of triumph and joy, and here I learned the sweet lesson of love that has echoed its jubilant note through all the years, and will until we reach the golden gate, she and I, to which love holds the key.

At the south gate the “gossip benches” are filled. The old men smoke their pipes and doff their caps to “the American” with the cheery welcome of friends who knew and spanked him with hearty good will when as “a kid” he absconded with their boats for a surreptitious expedition up to the lake.

The night comes on. The people are returning from their evening constitutional, walking in the middle of the street and taking off their hats to their neighbors as they pass. It is their custom, and the American habit of nodding to friends is held to be evidence of backwoods’ manners excusable only in a people so new. In the deep recesses of the Domkirke dark shadows are gathering. The tower clock peals forth. At the last stroke the watchman lifts up his chant in a voice that comes quavering down from bygone ages:—

Ho, watchman! heard ye the clock strike ten?

This hour is worth the know—ing

Ye house-holds high and low,

The time is here and go—ing

When ye to bed should go;

Ask God to guard, and say A—men!

Be quick and bright, Watch fire and light,

our clock just now struck ten.

Bright and early the next morning I found women at work sprinkling white sand in the street in front of my door, and strewing it with winter-green and twigs of hemlock. Some one was dead, and the funeral was to pass that way. Indeed they all did. The cemetery was at the other end of the street. It was one of the inducements held out to my mother she told me, when father died, to move from the old home into that street. Now that she was quite alone, it was so “nice and lively; all the funerals passed by.” The one buried that day I had known, or she had known me in my boyhood, and it was expected that I would attend.

My mother sent the wreath that belongs,—there is both sense and sentiment in flowers at a funeral when they are wreathed by the hands of those who loved the dead, as is still the custom here; none where they are bought at a florist’s and paid for with a growl,—and we stood around the coffin and sang the old hymns, then walked behind it, two by two, men and women, to the grave, singing as we passed through the gate.

“Earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust.” The clods rang upon the coffin with almost cheerful sound, for she whose mortal body lay within was full of years and very tired. The minister paused. From among the mourners came forth the nearest relative and stood by the grave, hat in hand. Ours were all off. “From my heart I thank you, neighbors all,” he said, and it was over. We waited to shake hands, to speculate on the weather, safe topic even at funerals; then went each to his own.

I went down by the cloister walk and sat upon a bench and thought of it all. The stork had built its nest there on the stump of a broken tree, and was hatching its young. The town lay slumbering in the sunlight and the blossoming elders. The far tinkle of a bell came sleepily over the hedges.

When I was rested, I journeyed through the islands to find old friends, and found them. The heartiness of the welcome that met me everywhere! No need of their telling me they were glad to see me. It shone out of their faces and all over them. I shall always remember that journey: the people in the cars that were forever lunching and urging me to join in, though we had never met before. Were we not fellow-travellers? How, then, could we be strangers?

And when they learned I was from New York, the inquiries after Hans or Fritz, somewhere in Nebraska or Dakota. Had I ever met them? and, if I did, would I tell them I had seen father, mother, or brother, and that they were well? And would I come and stay with them a day or two? It was with very genuine regret that I had mostly to refuse. My vacation could not last forever. As it was, I packed it full enough to last me for many summers.

Through forest and field, over hill and vale, into the deep, gloomy moor went my way. The moor was ever most to my liking. I was born on the edge of it, and once its majesty has sunk into a human soul, that soul is forever after attuned to it. How little we have the making of ourselves. And how much greater the need that we should make of that little the most.

All my days I have been preaching against heredity as the arch-enemy of hope and effort, and here is mine, holding me fast. When I see, rising out of the dark moor, the lonely cairn that sheltered the bones of my fathers before the White Christ preached peace to their land, a great yearning comes over me. There I want to lay mine. There I want to sleep, under the heather where the bees hum drowsily in the purple broom at noonday and white shadows walk in the night. Mist from the marshes they are, but the people think them wraiths. Half heathen yet, am I? Yes, if to yearn for the soil whence you sprang is to be a heathen, heathen am I, not half, but whole, and will be all my days.

But not so. He is the heathen who loves not his native land. Thor long since lost his grip on the sons of the vikings. Never did the White Christ work greater transformation in a people, once so fierce, now so gentle unless when fighting for its firesides. Forest and field teem with legends that tell of it; tell of the battle between the old and the new, and the victory of peace. Every hilltop bears witness to it.

The old town ever had its own ways. They were mostly good ways, though sometimes odd. Who but a Ribe citizen would have thought of Knud Clausen’s way of doing my wife honor on the Sunday morning when, as a young girl, she went to church to be confirmed? Her father and Knud were neighbors and Knud’s barn-yard was a sore subject between them, being right under the other’s dining-room window.

He sometimes protested and oftener offered to buy, but Knud would neither listen nor sell. But he loved the ground his neighbor’s pretty daughter walked upon, as did, indeed, every poor man in the town, and on her Sunday he showed it by strewing the offensive pile with fresh cut grass and leaves, and sticking it full of flowers. It was well meant, and it was Danish all over. Stick up for your rights at any cost. These secure, go any length to oblige a neighbor.

Journeying so, I came from the home of dead kings at last to that of the living,—old King Christian, beloved of his people,—where once my children horrified the keeper of Rosenborg Palace by playing “the Wild Man of Borneo” with the official silver lions in the great knights’ hall. And I saw the old town no more. But in my dreams I walk its peaceful streets, listen to the whisper of the reeds in the dry moats about the green castle hill, and hear my mother call me once more her boy. And I know that I shall find them, with my lost childhood, when we all reach home at last.

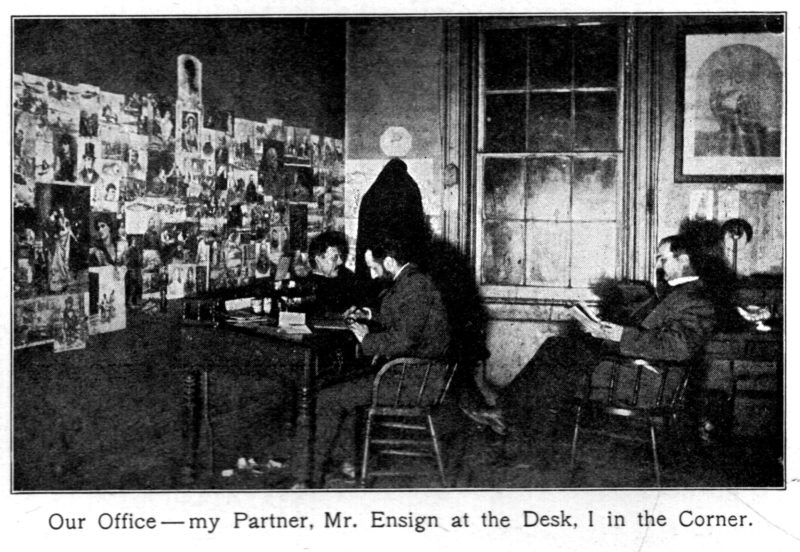

LONG ago, when I found my work beginning to master me, I put up a nest of fifty pigeonholes in my office so that with system I might get the upper hand of it; only to find, as the years passed, that I had got fifty tyrants for one.

LONG ago, when I found my work beginning to master me, I put up a nest of fifty pigeonholes in my office so that with system I might get the upper hand of it; only to find, as the years passed, that I had got fifty tyrants for one.

One pigeonhole contained most of the “honors” that have come to me of late years,—the nominations to membership in societies, guilds, and committees, in conventions at home and abroad,—most of them declined. Not that I’m insensible of the real honor intended by such tokens. I do not hold them lightly. I value the good opinion of my fellow-men, for with it comes increased power to do things.

But I would reserve the honors for those who have fairly earned them, and on whom they sit easy. They don’t on me. I am not ornamental by nature. Now that I have told all there is to tell, the reader is at liberty to agree with my little boy concerning the upshot of it. He was having a heart-to-heart talk with his mother the other day, in the course of which she told him that we must be patient; no one in the world was all good except God.

“And you,” said he, admiringly. He is his father’s son.

She demurred, but he stoutly maintained his own.

“I’ll bet you,” he said, “if you were to ask lots of people around here they would say you were fine. But”—he struggled reflectively with a button—”Gee! I can’t understand why they make such a fuss about papa.”

Out of the mouth of babes, etc. The boy is right. I cannot either, and it makes me feel small. I did my work and tried to put into it what I thought citizenship ought to be, when I made it out. I wish I had made it out earlier for my own peace of mind. And that is all there is to it.

For hating the slum what credit belongs to me? Who could love it? When it comes to that, perhaps it was the open, the woods, the freedom of my Danish fields I loved, the contrast that was hateful. I hate darkness and dirt anywhere, and naturally want to let in the light. I will have no dark corners in my own cellar; it must be whitewashed clean. Nature, I think, intended me for a cobbler, or a patch-tailor. I love to mend and make crooked things straight. When I was a carpenter I preferred to make an old house over to building a new.

My office years ago became notorious as a sort of misfit shop where things were matched that had got mislaid in the hurry and bustle of life, in which some of us always get shoved aside. Some one has got to do that, and I like the job; which is fortunate, for I have no head for creative work of any kind. The publishers bother me to write a novel; editors want me on their staffs. I shall do neither, for the good reason that I am neither poet, philosopher, nor, I was going to say, philanthropist; but leave me that. I would love my fellow-man. For the rest I am a reporter of facts. And that I would remain. So, I know what I can do and how to do it best.

We all love power—to be on the winning side. You cannot help being there when you are fighting the slum, for it is the cause of justice and right. I said it before, but it will bear to be said again, not once but many times: every defeat in such a fight is a step toward victory, taken in the right spirit. In the end you will come out ahead. The power of the biggest boss is like chaff in your hands. You can see his finish. And he knows it. Hence, even he will treat you with respect. However he try to bluff you, he is the one who is afraid. The boss has the courage of the brute, or he would not be boss; but when it comes to a moral issue he is the biggest coward in the lot. The bigger the brute the more abject its terror at what it does not understand.

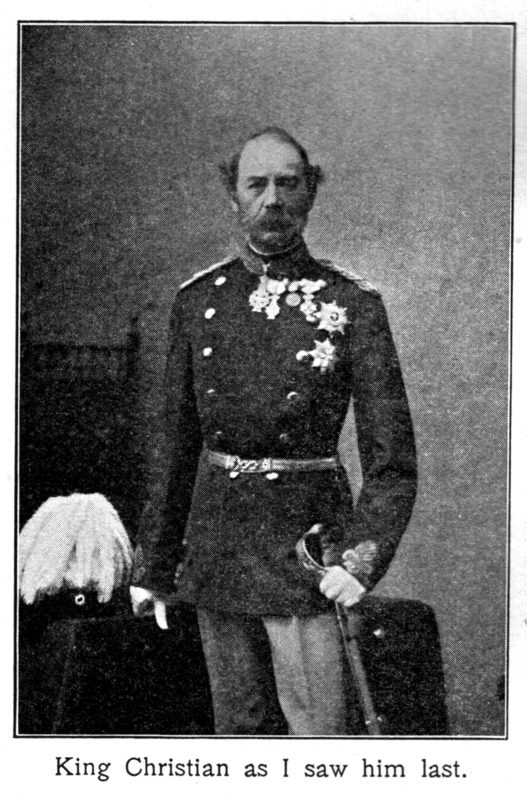

Some of the honors I refused; there were some my heart craved, and I could not let them go. There hangs on my wall the passport Governor Roosevelt gave me when I went abroad, dearer to me than sheepskin or degree, for the heart of a friend is in it. What would I not give to be worthy of its faithful affection! Sometimes when I go abroad I wear upon my breast a golden cross which King Christian gave me. It is the old Crusaders’ cross, in the sign of which my stern forefathers conquered the heathen and themselves on many a hard-fought field.

My father wore it for long and faithful service to the State. I rendered none. But though I did nothing to deserve it, I wear the cross proudly for the love I bear the flag under which I was born and the good old King who gave it to me. I saw him often when I was a young lad.

Of my last meeting with King Christian I mean to let my American fellow-citizens know so that they may understand what manner of man is he whom they call in Europe its “first gentleman” and in Denmark “the good King.”

But first I shall have to tell how my father came to wear the cross of Dannebrog. He was very old at the time; retired long since from his post which he had filled faithfully forty years and more. In some way, I never knew quite how, they passed him by with the cross at the time of the retirement. Perhaps he had given offence by refusing a title. He was an independent old man, and cared nothing for such things; but I knew that the cross he would gladly have worn for the King he had served so well. And when he sat in the shadow, with the darkness closing in, I planned to get it for him as the one thing I knew would give him pleasure.

But the official red tape was stronger than I; until one day, roused to anger by it all, I wrote direct to the King and told him about it. I showed him the wrong that had been done, and told him that I was sure he would set it right as soon as he knew of it. And I was not mistaken. The old town was put into a great state of excitement and mystification when one day there arrived in a large official envelope, straight from the King, the cross long since given up; for, indeed, the Minister had told me that, my father having been retired, the case was closed. The injustice that had been done was itself a bar to its being undone; there was no precedent for such action.

That was what I told the King, and also that it was his business to set precedents, and he did. Four years later, when I took my children home to let my father bless them,—they were his only grandchildren and he had never seen any of them,—he sat in his easy chair and wondered yet at the queer way in which that cross came. And I marvelled with him. He died without knowing how I had interfered. It was better so.

It was when I went home to mother that I met King Christian last. They had told me the right way to approach the King, the proper number of bows and all that, and I meant to faithfully observe it all. I saw a tired and lonely old man, to whom my heart went out on the instant, and I went right up and shook hands, and told him how much I thought of him and how sorry I was for his losing his wife, the Queen Louise, whom everybody loved.

He looked surprised a moment; then such a friendly look came into his face, and I thought him the handsomest King that ever was. He asked about the Danes in America, and I told him they were good citizens, better for not forgetting their motherland and him in his age and loss. He patted my hand with a glad little laugh, and bade me tell them how much he appreciated it, and how kindly his thoughts were of them all. As I made to go, after a long talk, he stopped me and, touching the little silver cross on my coat lapel, asked what it was.

I told him; told him of the motto, “In His Name,” and of the labor of devoted women in our great country, to make it mean what it said. As I spoke I remembered my father, and I took it off and gave it to him, bidding him keep it, for surely few men could wear it so worthily. But he put it back into my hand; he could not take it from me, he said. And so we parted.

I thought with a pang of remorse, as I stood in the doorway, of the parting bow I had forgotten, and turned around to make good the omission. There stood the King in his blue uniform, with a smile so full of kindness, that I—why, I just nodded back and waved my hand. It was very improper, I dare say; perfectly shocking; but never was heartier greeting to king. I meant every bit of it.

The next year he sent me his cross of gold for the one of silver I offered him. I wear it gladly, for the knighthood it confers pledges to the defence of womanhood and of little children, and if I cannot wield lance and sword as the king’s men of old, I can wield the pen. It may be that in the providence of God the shedding of ink in the cause of right shall set the world farther ahead in our day than the blood-letting of all the ages past.

These I could not forego. Neither, when friends gathered in the King’s Daughters’ Settlement on our silver wedding day, and with loving words gave to the new house my name, could I say them nay. It stands, that house, within a stone’s throw of many a door in which I sat friendless and forlorn, trying to hide from the policeman who would not let me sleep; within hail of the Bend of the wicked past, atoned for at last; of the Bowery boarding-house where I lay senseless on the stairs after my first day’s work in the newspaper office, starved well-nigh to death.

But the memory of the old days has no sting. Its message is one of hope; the house itself is the key-note. It is the pledge of a better day, of the defeat of the slum with its helpless heredity of despair. That shall damn no longer lives yet unborn. Children of God are we! that is our challenge to the slum, and on earth we shall claim yet our heritage of light.

With the home preserved we may look forward without fear; there is no question that can be asked of the Republic to which we shall not find the answer. We may not always agree as to what is right; but, starting there, we shall be seeking the right, and seeking we shall find it. Ruin and disaster are at the end of the road that starts from the slum.

Perhaps it is easy for me to preach contentment. With a mother who prays, a wife who fills the house with song, and the laughter of happy children about me, all my dreams come true or coming true, why should I not be content? In fact, I know of no better equipment for making them come true: faith in God to make all things possible that are right; faith in man to get them done; fun enough in between to keep them from spoiling or running off the track into useless crankery. An extra good sprinkling of that! The longer I live the more I think of humor as the saving sense.

Looking back over thirty years it seems to me that never had man better a time than I. Enough of the editor chaps there were always to keep up the spirits. The hardships people write to me about were not worth while mentioning; and anyway they had to be, to get some of the crankery out of me, I guess. But the friendships endure. For all the rebuffs of my life they have more than made up. When I think of them, of the good men and women who have called me friend, I am filled with wonder and gratitude. I know the police might not have approved of all of them. But, then, police approval is not a certificate of character to one who has lived the best part of his life in Mulberry Street.

The police would certainly disapprove of Dr. Parkhurst, whom I am glad to call my friend. They might even object to Bishop Potter, whose friendship I return with a warmth that is nowise dampened by his disapproval of reporters.

Ahead there is light. Even as I write the little ones from Cherry Street are playing on the grass under my trees. The time is at hand when we shall bring to them in their slum the things which we must now bring them to see, and then the slum will be no more. How little we grasp the meaning of it all.

Ahead there is light. Even as I write the little ones from Cherry Street are playing on the grass under my trees. The time is at hand when we shall bring to them in their slum the things which we must now bring them to see, and then the slum will be no more. How little we grasp the meaning of it all.

In a report of the Commissioner of Education I read the other day that of kindergarten children in an Eastern city who were questioned 63 per cent did not know a robin, and more than half had not seen a dandelion in its yellow glory.

And yet we complain that our cities are misgoverned! You who think that the teaching of “civics” in the school covers it all, I am not speaking to you. You will never understand. But the rest of you who are willing to sit with me at the feet of little Molly and learn from her, listen: She was poor and ragged and starved. Her home was a hovel. We were debating, some good women who knew her and I, how best to make a merry Christmas for her, and my material mind hung upon clothes and boots, for it was in Chicago. But the vision of her soul was a pair of red shoes! Her heart craved them. Yes, and she got them. Not for all the gold in the Treasury would I have trodden it under in pork and beans, smothered it in—no, not in rubber boots, though the mud in the city by the lake be both deep and black.

They were the window, those red shoes, through which her little captive soul looked out and yearned for the beauty of God’s great world. Could I forget the blue boots with the tassels which I worshiped in my boyhood? Nay, friends, the robin and the dandelion we must put back into those barren lives if we would have good citizenship. They and the citizenship are first cousins. We robbed the children of them, or stood by and saw it done, and it is for us to restore them. That is my answer to the missionary who writes to ask what is the “most practical way of making good Christians and American citizens” out of the emigrants who sit heavy on her conscience, as well they may. Christianity without the robin and the dandelion is never going to reach down into the slum; American citizenship without them would leave the slum there, to dig the grave of it and of the republic.

The Bend is gone; the Barracks are gone; Mulberry Street itself as I knew it so long is gone. Cat Alley, whence came the deputation of ragamuffins to my office demanding flowers for “the lady in the back,” the poor old scrubwoman who lay dead in her dark basement, went when the Elm Street widening let light into the heart of our block. The old days are gone. I myself am gone. A year ago I had warning that “the night cometh when no man can work,” and Mulberry Street knew me no more. I am still a young man, not far past fifty, and I have much I would do yet. But what if it were ordered otherwise? I have been very happy. No man ever had so good a time. Should I not be content?

I dreamed a beautiful dream in my youth, and I awoke and found it true. My silver bride they called her just now. The frost is upon my head, indeed; hers winter has not touched with its softest breath. Her footfall is the lightest, her laugh the merriest in the house. Sometimes when she sings with the children I sit and listen, and with her voice there comes to me as an echo of the words in her letter, that blessed first letter in which she wrote: “We will strive together for all that is noble and good.” So she saw her duty as a true American, and she has kept the pledge.

I have told the story of the making of an American. There remains to tell how I found out that he was made and finished at last. It was when I went back to see my mother once more and, wandering about the country of my childhood’s memories, had come to the city of Elsinore. There I fell ill of a fever and lay many weeks in the house of a friend upon the shore of the beautiful Oeresund. One day when the fever had left me they rolled my bed into a room overlooking the sea. The sunlight danced upon the waves, and the distant mountains of Sweden were blue against the horizon. Ships passed under full sail up and down the great waterway of the nations.

But the sunshine and the peaceful day bore no message to me. I lay moodily picking at the coverlet, sick and discouraged and sore—I hardly knew why myself. Until all at once there sailed past, close inshore, a ship flying at the top the flag of freedom, blown out on the breeze till every star in it shone bright and clear.

That moment I knew. Gone were illness, discouragement, and gloom! Forgotten weakness and suffering, the cautions of doctor and nurse. I sat up in bed and shouted, laughed and cried by turns, waving my handkerchief to the flag out there. They thought I had lost my head, but I told them no, thank God! I had found it, and my heart, too, at last.

I knew then that it was my flag; that my children’s home was mine, indeed; that I also had become an American in truth. And I thanked God, and, like unto the man sick of the palsy, arose from my bed and went home, healed.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

By subscribing, you will automatically receive the latest episodes downloaded to your computer or portable device. Select your preferred subscription method above.

To subscribe via a different application: Go to your favorite podcast application or news reader and enter this URL: https://clearwaterpress.com/byline/feed/podcast/