Twas Liza’s Doings

Episode 9 •

Twas Liza’s Doings

• In those days somebody was always fighting somebody else for some fancied injury or act of bad faith in the gathering of the news.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Email | TuneIn | RSS

SHOW NOTES ____________

The Making of an American (excerpt from chapter 9)

By Jacob Riis

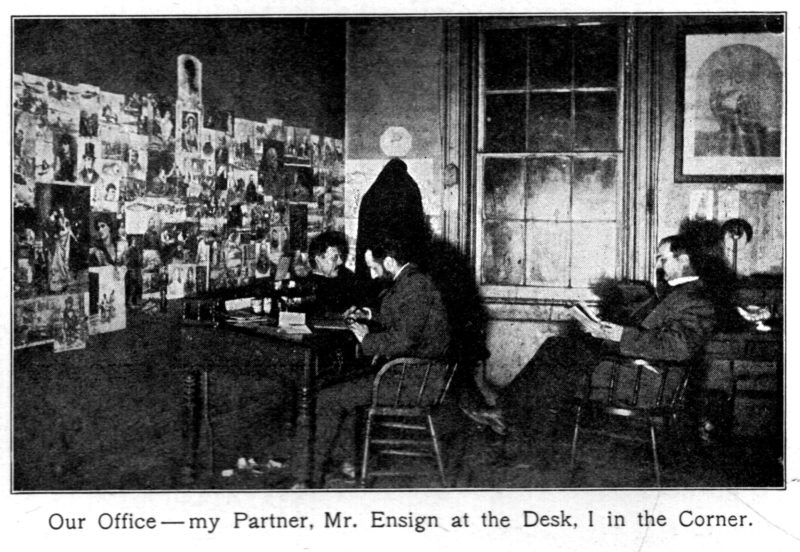

[The] Mulberry Street [office] in those days was prone to … [feuds]. Somebody was always fighting somebody else for some fancied injury or act of bad faith in the gathering of the news. For the time being they all made common cause against the reporter of the Tribune, who also represented the local bureau of the Associated Press. They hailed the coming of “the Dutchman” with shouts of derision, and decided, I suppose, to finish me off while I was new. So they pulled themselves together for an effort, and within a week I was so badly “beaten” in the Police Department, in the Health Department, in the Fire Department, the Coroner’s office, and the Excise Bureau, all of which it was my task to cover, that the manager of the Press Bureau called me down to look me over. He reported to the Tribune that he did not think I would do. But Mr. Shanks told him to wait and see. In some way I heard of it, and that settled it that I was to win. I might be beaten in many a battle, but how could I lose the fight with a general like that?

And, indeed, in another week it was their turn to be called down to give an account of themselves. The “Dutchman” had stolen a march on them. I suppose it was to them a very astounding thing, yet it was perfectly simple. Their very strength, as they held it to be, was their weakness. They were a dozen against one, and each one of them took it for granted that the other eleven were attending to business and that he need not exert himself overmuch.

The immediate result of this first victory of mine was a whirlwind onslaught on me, fiercer than anything that had gone before. I expected it and met it as well as I could, holding my own after a fashion. When, from sheer exhaustion, they let up to see if I was still there, I paid them back with two or three “beats” I had stored up for the occasion. And then we settled down to the ten years’ war for the mastery, out of which I was to come at last fairly the victor, and with the only renown I have ever coveted or cared to have, that of being the “boss reporter” in Mulberry Street.

I have so often been asked in later years what my work was there, and how I found there the point of view from which I wrote my books, that I suppose I shall have to go somewhat into the details of it.

The police reporter on a newspaper, then, is the one who gathers and handles all the news that means trouble to some one: the murders, fires, suicides, robberies, and all that sort, before it gets into court. He has an office in Mulberry Street, across from Police Headquarters, where he receives the first intimation of the trouble through the precinct reports. Or else he does not receive it.

The police do not like to tell the public of a robbery or a safe “cracking,” for instance. They claim that it interferes with the ends of justice. What they really mean is that it brings ridicule or censure upon them to have the public know that they do not catch every thief, or even most of them. They would like that impression to go out, for police work is largely a game of bluff.

Here, then, is an opportunity for the “beats” I speak of. The reporter who, through acquaintance, friendship, or natural detective skill, can get that which it is the policy of the police to conceal from him, wins. It may seem to many a reader a matter of no great importance if a man should miss a safe-burglary for his paper; but reporting is a business, a very exacting one at that, and if he will stop a moment and think what it is he instinctively looks at first in his morning paper, even if he has schooled himself not to read it through, he will see it differently.

The fact is that it is all a great human drama in which these things are the acts that mean grief, suffering, revenge upon somebody, loss or gain. The reporter who is behind the scenes sees the tumult of passions, and not rarely a human heroism that redeems all the rest. It is his task so to portray it that we can all see its meaning, or at all events catch the human drift of it, not merely the foulness and the reek of blood. If he can do that, he has performed a signal service, and his murder story may easily come to speak more eloquently to the minds of thousands than the sermon preached to a hundred in the church on Sunday.

Of the advantages that smooth the way to news-getting I had none. I was a stranger, and I was never distinguished for detective ability. But good hard work goes a long way toward making up for lack of genius. Any seemingly innocent slip sent out from the police telegraph office across the way recording a petty tenement-house fire might hide a fire-bug, who always makes shuddering appeal to our fears; the finding of John Jones sick and destitute in the street meant, perhaps, a story full of the deepest pathos.

Indeed, I can think of a dozen now that did. I see before me, as though it were yesterday, the desolate Wooster Street attic, with wind and rain sweeping through the bare room in which lay dying a French nobleman of proud and ancient name, the last of his house. He was one of my early triumphs. New York is a queer town. The grist of every hopper in the world comes to it.

Did I settle in full? Yes, I did. I was in a fight not of my own choosing, and I was well aware that my turn was coming. I hit as hard as I knew how, and so did they. When I speak of “triumphs,” it is professionally. There was no hard-heartedness about it. We did not gloat over the misfortunes we described. We were reporters, not ghouls.

There lies before me as I write a letter that came in the mail this afternoon from a woman who bitterly objects to my diagnosis of the reporter’s as the highest and noblest of all callings. She signs herself “a sufferer from reporters’ unkindness,” and tells me how in the hour of her deep affliction they have trodden upon her heart. Can I not, she asks, encourage a public sentiment that will make such reporting disreputable? All my life I have tried to do so, and, in spite of the evidence of yellow journalism to the contrary, I think we are coming nearer to that ideal; in other words, we are emerging from savagery. Striving madly for each other’s scalps as we were, I do not think that we scalped any one else unjustly. I know I did not.

They were not particularly scrupulous, I am bound to say. In their rage and mortification at having underestimated the enemy, they did things unworthy of men and of reporters. They stole my slips in the telegraph office and substituted others that sent me off on a wild-goose chase to the farthest river wards in the midnight hour, thinking so to tire me out. But they did it once too often. I happened on a very important case on such a trip, and made the most of it, telegraphing down a column or more about it from the office, while the enemy watched me helplessly from the Headquarters’ stoop across the way.

They were gathered there, waiting for me to come back, and received me with loud and mocking ahems! and respectfully sympathetic toots on a tin horn, kept for that purpose. Its voice had a mournful strain in it that was especially exasperating. But when, without paying any attention to them, I busied myself with the wire at once, and kept at it right along, they scented trouble, and consulted anxiously among themselves. My story finished, I went out and sat on my own stoop and said ahem! in my turn in as many aggravating ways as I could.

They knew they were beaten then, and shortly they had confirmation of it. The report came in from the precinct at 2 A.M., but it was then too late for their papers, for there were no telephones in those days. I had the only telegraph wire. After that they gave up such tricks, and the Tribune saved many cab fares at night; for there were no elevated railroads, either, in those days, or electric or cable cars.

On the other hand, this enterprise of ours was often of the highest service to the public. When, for instance, in following up a case of destitution and illness involving a whole family, I, tracing back the origin of it, came upon a party at which ham sandwiches had been the bill of fare, and upon looking up the guests, found seventeen of the twenty-five sick with identical symptoms, it required no medical knowledge, but merely the ordinary information and training of the reporter, to diagnose trichinosis. The seventeen had half a dozen different doctors, who, knowing nothing of party or ham, were helpless, and saw only cases of rheumatism or such like. I called as many of them as I could reach together that night, introduced them to one another and to my facts, and asked them what they thought then.

What they thought made a sensation in my paper the next morning, and practically decided the fight, though the enemy was able to spoil my relish for the ham by reporting the poisoning of a whole family with a dish of depraved smelt while I was chasing up the trichinae. However, I had my revenge. I walked in that afternoon upon Dr. Cyrus Edson at his microscope surrounded by my adversaries, who besought him to deny my story. The doctor looked quizzically at them and made reply:—

“I would like to oblige you, boys, but how I can do it with those fellows squirming under the microscope I don’t see. I took them from the flesh of one of the patients who was sent to Trinity Hospital to-day. Look at them yourself.”

He winked at me, and, peering into his microscope, I saw my diagnosis more than confirmed. There were scores of the little beasts curled up and burrowing in the speck of tissue. The unhappy patient died that week.

We had our specialties in this contest of wits. One was distinguished as a sleuth. He fed on detective mysteries as a cat on a chicken-bone. He thought them out by day and dreamed them out by night, to the great exasperation of the official detectives, with whom their solution was a commercial, not in the least an intellectual, affair. They solved them on the plane of the proverbial lack of honor among thieves, by the formula, “You scratch my back, and I’ll scratch yours.”

Another came out strong on fires. He knew the history of every house in town that ran any risk of being burned; knew every fireman; and could tell within a thousand dollars, more or less, what was the value of the goods stored in any building in the dry-goods district, and for how much they were insured. If he couldn’t, he did anyhow, and his guesses often came near the fact, as shown in the final adjustment. He sniffed a firebug from afar, and knew without asking how much salvage there was in a bale of cotton after being twenty-four hours in the fire. He is dead, poor fellow.

In life he was fond of a joke, and in death the joke clung to him in a way wholly unforeseen. The firemen in the next block, with whom he made his headquarters when off duty, so that he might always be within hearing of the gong, wished to give some tangible evidence of their regard for the old reporter, but, being in a hurry, left it to the florist, who knew him well, to choose the design. He hit upon a floral fire-badge as the proper thing, and thus it was that when the company of mourners was assembled, and the funeral service in progress, there arrived and was set upon the coffin, in the view of all, that triumph of the florist’s art, a shield of white roses, with this legend written across it in red immortelles: “Admit within fire lines only.” It was shocking, but irresistible. It brought down even the house of mourning.

I might fill many pages with such stories, but I shall not attempt it. Do they seem mean and trifling in the retrospect? Not at all. They were my work, and I liked it.

It is not to be supposed that all this was smooth sailing. Along with the occasional commendations for battles won against “the mob” went constant and grievous complaints of the editors supplied by the Associated Press, and even by some in my own office now and then, of my “style.” It was very bad, according to my critics, altogether editorial and presuming, and not to be borne. So I was warned that I must mend it and give the facts, sparing comments.

By that I suppose they meant that I must write, not what I thought, but what they probably might think of the news. But, good or bad, I could write in no other way, and kept right on. Not that I think, by any manners of means, that it was the best way, but it was mine.

And goodness knows I had no desire to be an editor. I have not now. I prefer to be a reporter and deal with the facts to being an editor and lying about them. In the end the complaints died out. I suppose I was given up as hopeless.

Perhaps there had crept into my reports too much of my fight with the police. For by that time I had included them in “the opposition.” They had not been friendly from the first, and it was best so. I had them all in front then, and an open enemy is better any day than a false friend who may stab you in the back. In the quarter of a century since, I have seldom been on any other terms with the police. I mean with the heads of them. The rank and file, the man with the nightstick as Roosevelt liked to call him, is all right, if properly led. He has rarely been properly led. It may be that, in that respect at least, my reports might have been tempered somewhat to advantage. Though I don’t know. I prefer, after all, to have it out, all out. And it did come out, and my mind was relieved; which was something.

And now that this chapter, somewhat against my planning, has become wholly the police reporter’s, I shall have to bring up my cause celebre, though that came a long while after my getting into Mulberry Street. It illustrates very well that which I have been trying to describe as a reporter’s public function. We had been for months in dread of a cholera scourge that summer, when, mousing about the Health Department one day, I picked up the weekly analysis of the Croton water and noticed that there had been for two weeks past “a trace of nitrites” in the water. I asked the department chemist what it was. He gave an evasive answer, and my curiosity was at once aroused. There must be no unknown or doubtful ingredient in the water supply of a city of two million souls. Like Caesar’s wife, it must be above suspicion.

Within an hour I had learned that the nitrites meant in fact that there had been at one time sewage contamination; consequently that we were face to face with a most grave problem. How had the water become polluted, and who guaranteed that it was not in that way even then, with the black death threatening to cross the ocean from Europe?

I sounded the warning in my paper, then the Evening Sun, counseled the people to boil the water pending further discoveries, then took my camera and went up in the watershed. I spent a week there, following to its source every stream that discharged into the Croton River and photographing my evidence wherever I found it.

When I told my story in print, illustrated with the pictures, the town was astounded. The Board of Health sent inspectors to the watershed, who reported that things were worse a great deal than I had said. Populous towns sewered directly into our drinking-water. There was not even a pretence at decency. The people bathed and washed their dogs in the streams. The public town dumps were on their banks.

The rival newspapers tried to belittle the evil because their reporters were beaten. Running water purifies itself, they said. So it does, if it runs far enough and long enough. I put that matter to the test. Taking the case of a town some sixty miles out of New York, one of the worst offenders, I ascertained from the engineer of the water-works how long it ordinarily took to bring water from the Sodom reservoir just beyond, down to the housekeepers’ faucets in the city. Four days, I think it was. Then I went to the doctors and asked them how many days a vigorous cholera bacillus might live and multiply in running water. About seven, said they. My case was made.

The health inspectors’ report clinched the matter. The newspapers editorially abandoned their reporters to ridicule and their fate. The city had to purchase a strip of land along the streams wide enough to guard against direct pollution. It cost millions of dollars, but it was the merest trifle to what a cholera epidemic would have meant to New York in loss of commercial prestige, let alone human lives. The contention over that end of it was transferred to Albany, where the politicians took a hand. What is there they do not exploit? Years after, meeting one of them who knew my share in it, he asked me, with a wink and a confidential shove, “how much I got out of it.” When I told him “nothing,” I knew that upon my own statement he took me for either a liar or a fool, the last being considerably the worse of the two alternatives.

In all of this battlesome account I have said nothing about the biggest fight of all. I had that with myself. In the years that had passed I had never forgotten the sergeant in the Church Street police station, and my dog. It is the kind of thing you do not get over. Way back in my mind there was the secret thought, the day I went up to Mulberry Street, that my time was coming at last. And now it had come. I had a recognized place at Headquarters, and place in the police world means power, more or less. The backing of the Tribune had given me influence. Enough for revenge! At the thought I flushed with anger. It has power yet to make my blood boil, the thought of that night in the station-house.

It was then my great temptation came. No doubt the sergeant was still there. If not, I could find him. I knew the day and hour when it happened. They were burned into my brain. I had only to turn to the department records to find out who made out the returns on that October morning while I was walking the weary length of the trestle-work bridge across Raritan Bay, to have him within reach. There were a hundred ways in which I could hound him then, out of place and pay, even as he had driven me forth from the last poor shelter and caused my only friend to be killed.

Speak not to me of the sweetness of revenge! Of all unhappy mortals the vengeful man must be the most wretched. I suffered more in the anticipation of mine than ever I had when smarting under the injury, grievous as the memory of it is to me even now. Day after day I went across the street to begin the search. For hours I lingered about the record clerk’s room where they kept the old station-house blotters, unable to tear myself away. Once I even had the one from Church Street of October, 1870, in my hands; but I did not open it. Even as I held it I saw another and a better way. I would kill the abuse, not the man who was but the instrument and the victim of it. For never was parody upon Christian charity more corrupting to human mind and soul than the frightful abomination of the police lodging-house, sole provision made by the municipality for its homeless wanderers. Within a year I have seen the process in full operation in Chicago, have heard a sergeant in the Harrison Street Station there tell me, when my indignation found vent in angry words, that they “cared less for those men and women than for the cur dogs in the street.”

Exactly so! My sergeant was of the same stamp. Those dens, daily association with them, had stamped him. Then and there I resolved to wipe them out, bodily, if God gave me health and strength. And I put the book away quick and never saw it again. I do not know till this day who the sergeant was, and I am glad I do not. It is better so.

Twas Liza’s Doings

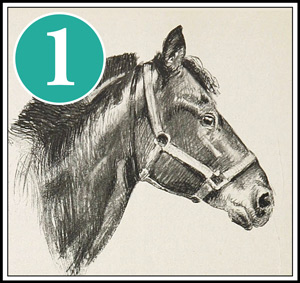

JOE drove his old gray mare along the stony road in deep thought. They had been across the ferry to Newtown with a load of Christmas truck. It had been a hard pull uphill for them both, for Joe had found it necessary not a few times to get down and give old ’Liza a lift to help her over the roughest spots; and now, going home, with the twilight coming on and no other job a-waiting, he let her have her own way. It was slow, but steady, and it suited Joe; for his head was full of busy thoughts, and there were few enough of them that were pleasant.

Business had been bad at the big stores, never worse, and what trucking there was there were too many about. Storekeepers who never used to look at a dollar, so long as they knew they could trust the man who did their hauling, were counting the nickels these days. As for chance jobs like this one, that was all over now with the holidays, and there had been little enough of it, too.

There would be less, a good deal, with the hard winter at the door, and with ’Liza to keep and the many mouths to fill. Still, he wouldn’t have minded it so much but for mother fretting and worrying herself sick at home, and all along o’ Jim, the eldest boy, who had gone away mad and never come back. Many were the dollars he had paid the doctor and the druggist to fix her up, but it was no use. She was worrying herself into a decline, it was clear to be seen.

Joe heaved a heavy sigh as he thought of the strapping lad who had brought such sorrow to his mother. So strong and so handy on the wagon. Old ’Liza loved him like a brother and minded him even better than she did himself. If he only had him now, they could face the winter and the bad times, and pull through. But things never had gone right since he left. He didn’t know, Joe thought humbly as he jogged along over the rough road, but he had been a little hard on the lad. Boys wanted a chance once in a while. All work and no play was not for them. Likely he had forgotten he was a boy once himself. But Jim was such a big lad, ’most like a man. He took after his mother more than the rest. She had been proud, too, when she was a girl. He wished he hadn’t been hasty that time they had words about those boxes at the store. Anyway, it turned out that it wasn’t Jim’s fault. But he was gone that night, and try as they might to find him, they never had word of him since. And Joe sighed again more heavily than before.

Old ’Liza shied at something in the road, and Joe took a firmer hold on the reins. It turned his thoughts to the horse. She was getting old, too, and not as handy as she was. He noticed that she was getting winded with a heavy load. It was well on to ten years she had been their capital and the breadwinner of the house. Sometimes he thought that she missed Jim. If she was to leave them now, he wouldn’t know what to do, for he couldn’t raise the money to buy another horse nohow, as things were. Poor old ’Liza! He stroked her gray coat musingly with the point of his whip as he thought of their old friendship. The horse pointed one ear back toward her master and neighed gently, as if to assure him that she was all right.

Suddenly she stumbled. Joe pulled her up in time, and throwing the reins over her back, got down to see what it was. An old horseshoe, and in the dust beside it a new silver quarter. He picked both up and put the shoe in the wagon.

“They say it is luck,” he mused, “finding horse-iron and money. Maybe it’s my Christmas. Get up, ’Liza!” And he drove off to the ferry.

*

The glare of a thousand gas-lamps had chased the sunset out of the western sky, when Joe drove home through the city’s streets. Between their straight mile-long rows surged the busy life of the coming holiday. In front of every grocery-store was a grove of fragrant Christmas trees waiting to be fitted into little green stands with fairy fences. Within, customers were bargaining, chatting, and bantering the busy clerks. Peddlers offering tinsel and colored candles waylaid them on the door-step. The rack under the butcher’s awning fairly groaned with its weight of plucked geese, of turkeys, stout and skinny, of poultry of every kind. The saloon-keeper even had wreathed his door-posts in ground-ivy and hemlock, and hung a sprig of holly in the window, as if with a spurious promise of peace on earth and good-will toward men who entered there. It tempted not Joe. He drove past it to the corner, where he turned up a street darker and lonelier than the rest, toward a stretch of rocky, vacant lots fenced in by an old stone wall. ’Liza turned in at the rude gate without being told, and pulled up at the house.

A plain little one-story frame with a lean-to for a kitchen, and an adjoining stable-shed, over-shadowed all by two great chestnuts of the days when there were country lanes where now are paved streets, and on Manhattan Island there was farm by farm. A light gleamed in the window looking toward the street. As ’Liza’s hoofs were heard on the drive, a young girl with a shawl over her head ran out from some shelter where she had been watching, and took the reins from Joe.

“You’re late,” she said, stroking the mare’s steaming flank. ’Liza reached around and rubbed her head against the girl’s shoulder, nibbling playfully at the fringe of her shawl.

“Yes; we’ve come far, and it’s been a hard pull. ’Liza is tired. Give her a good feed, and I’ll bed her down. How’s mother?”

“Sprier than she was,” replied the girl, bending over the shaft to unbuckle the horse; “seems as if she’d kinder cheered up for Christmas.” And she led ’Liza to the stable while her father backed the wagon into the shed.

It was warm and very comfortable in the little kitchen, where he joined the family after “washing up.” The fire burned brightly in the range, on which a good-sized roast sizzled cheerily in its pot, sending up clouds of savory steam. The sand on the white pine floor was swept in tongues, old-country fashion. Joe and his wife were both born across the sea, and liked to keep Christmas eve as they had kept it when they were children. Two little boys and a younger girl than the one who had met him at the gate received him with shouts of glee, and pulled him straight from the door to look at a hemlock branch stuck in the tub of sand in the corner. It was their Christmas tree, and they were to light it with candles, red and yellow and green, which mama got them at the grocer’s where the big Santa Claus stood on the shelf. They pranced about like so many little colts, and clung to Joe by turns, shouting all at once, each one anxious to tell the great news first and loudest.

Joe took them on his knee, all three, and when they had shouted until they had to stop for breath, he pulled from under his coat a paper bundle, at which the children’s eyes bulged. He undid the wrapping slowly.

“Who do you think has come home with me?” he said, and he held up before them the veritable Santa Claus himself, done in plaster and all snow-covered. He had bought it at the corner toy-store with his lucky quarter. “I met him on the road over on Long Island, where ’Liza and I was to-day, and I gave him a ride to town. They say it’s luck falling in with Santa Claus, partickler when there’s a horseshoe along. I put his’n up in the barn, in ’Liza’s stall. Maybe our luck will turn yet, eh! old woman?” And he put his arm around his wife, who was setting out the dinner with Jennie, and gave her a good hug, while the children danced off with their Santa Claus.

She was a comely little woman, and she tried hard to be cheerful. She gave him a brave look and a smile, but there were tears in her eyes, and Joe saw them, though he let on that he didn’t. He patted her tenderly on the back and smoothed his Jennie’s yellow braids, while he swallowed the lump in his throat and got it down and out of the way. He needed no doctor to tell him that Santa Claus would not come again and find her cooking their Christmas dinner, unless she mended soon and swiftly.

They ate their dinner together, and sat and talked until it was time to go to bed. Joe went out to make all snug about ’Liza for the night and to give her an extra feed. He stopped in the door, coming back, to shake the snow out of his clothes. It was coming on with bad weather and a northerly storm, he reported. The snow was falling thick already and drifting badly. He saw to the kitchen fire and put the children to bed. Long before the clock in the neighboring church-tower struck twelve, and its doors were opened for the throngs come to worship at the midnight mass, the lights in the cottage were out, and all within it fast asleep.

The murmur of the homeward-hurrying crowds had died out, and the last echoing shout of “Merry Christmas!” had been whirled away on the storm, now grown fierce with bitter cold, when a lonely wanderer came down the street. It was a boy, big and strong-limbed, and, judging from the manner in which he pushed his way through the gathering drifts, not unused to battle with the world, but evidently in hard luck. His jacket, white with the falling snow, was scant and worn nearly to rags, and there was that in his face which spoke of hunger and suffering silently endured. He stopped at the gate in the stone fence, and looked long and steadily at the cottage in the chestnuts. No life stirred within, and he walked through the gap with slow and hesitating step. Under the kitchen window he stood awhile, sheltered from the storm, as if undecided, then stepped to the horse-shed and rapped gently on the door.

“’Liza!” he called, “’Liza, old girl! It’s me—Jim!”

A low, delighted whinnying from the stall told the shivering boy that he was not forgotten there. The faithful beast was straining at her halter in a vain effort to get at her friend. Jim raised a bar that held the door closed by the aid of a lever within, of which he knew the trick, and went in. The horse made room for him in her stall, and laid her shaggy head against his cheek.

“Poor old ’Liza!” he said, patting her neck and smoothing her gray coat, “poor old girl! Jim has one friend that hasn’t gone back on him. I’ve come to keep Christmas with you, ’Liza! Had your supper, eh? You’re in luck. I haven’t; I wasn’t bid, ’Liza; but never mind. You shall feed for both of us. Here goes!” He dug into the oats-bin with the measure, and poured it full into ’Liza’s crib.

“Fill up, old girl! and good night to you.” With a departing pat he crept up the ladder to the loft above, and, scooping out a berth in the loose hay, snuggled down in it to sleep. Soon his regular breathing up there kept step with the steady munching of the horse in her stall. The two reunited friends were dreaming happy Christmas dreams.

The night wore into the small hours of Christmas morning. The fury of the storm was unabated. The old cottage shook under the fierce blasts, and the chestnuts waved their hoary branches wildly, beseechingly, above it, as if they wanted to warn those within of some threatened danger. But they slept and heard them not. From the kitchen chimney, after a blast more violent than any that had gone before, a red spark issued, was whirled upward and beaten against the shingle roof of the barn, swept clean of snow. Another followed it, and another. Still they slept in the cottage; the chestnuts moaned and brandished their arms in vain. The storm fanned one of the sparks into a flame. It flickered for a moment and then went out. So, at least, it seemed. But presently it reappeared, and with it a faint glow was reflected in the attic window over the door. Down in her stall ’Liza moved uneasily. Nobody responding, she plunged and reared, neighing loudly for help. The storm drowned her calls; her master slept, unheeding.

But one heard it, and in the nick of time. The door of the shed was thrown violently open, and out plunged Jim, his hair on fire and his clothes singed and smoking. He brushed the sparks off himself as if they were flakes of snow. Quick as thought, he tore ’Liza’s halter from its fastening, pulling out staple and all, threw his smoking coat over her eyes, and backed her out of the shed. He reached in, and pulling the harness off the hook, threw it as far into the snow as he could, yelling “Fire!” at the top of his voice. Then he jumped on the back of the horse, and beating her with heels and hands into a mad gallop, was off up the street before the bewildered inmates of the cottage had rubbed the sleep out of their eyes and come out to see the barn on fire and burning up.

Down street and avenue fire-engines raced with clanging bells, leaving tracks of glowing coals in the snow-drifts, to the cottage in the chestnut lots. They got there just in time to see the roof crash into the barn, burying, as Joe and his crying wife and children thought, ’Liza and their last hope in the fiery wreck. The door had blown shut, and the harness Jim threw out was snowed under. No one dreamed that the mare was not there. The flames burst through the wreck and lit up the cottage and swaying chestnuts. Joe and his family stood in the shelter of it, looking sadly on. For the second time that Christmas night tears came into the honest truckman’s eyes. He wiped them away with his cap.

“Poor ’Liza!” he said.

A hand was laid with gentle touch upon his arm. He looked up. It was his wife. Her face beamed with a great happiness.

“Joe,” she said, “you remember what you read: ‘tidings of great joy.’ Oh, Joe, Jim has come home!”

She stepped aside, and there was Jim, sister Jennie hanging on his neck, and ’Liza alive and neighing her pleasure. The lad looked at his father and hung his head.

“Jim saved her, father,” said Jennie, patting the gray mare; “it was him fetched the engine.”

Joe took a step toward his son and held out his hand to him.

“Jim,” he said, “you’re a better man nor yer father. From now on, you’n I run the truck on shares. But mind this, Jim: never leave mother no more.”

And in the clasp of the two hands all the past was forgotten and forgiven. Father and son had found each other again.

“’Liza,” said the truckman, with sudden vehemence, turning to the old mare and putting his arm around her neck, “’Liza! It was your doin’s. I knew it was luck when I found them things. Merry Christmas!” And he kissed her smack on her hairy mouth, one, two, three times.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

By subscribing, you will automatically receive the latest episodes downloaded to your computer or portable device. Select your preferred subscription method above.

To subscribe via a different application: Go to your favorite podcast application or news reader and enter this URL: https://clearwaterpress.com/byline/feed/podcast/