The Author of Cyrano

Episode 27•

The Author of Cyrano

• I said that whatever he would write for me, on what ever subject, at what ever time, I would accept without question or reservation, and put on the stage at my own theater: rather a remarkable pledge, seeing that our acquaintance dated from about ten minutes back; but I meant exactly what I said.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Email | TuneIn | RSS

SHOW NOTES ____________

The Author of Cyrano

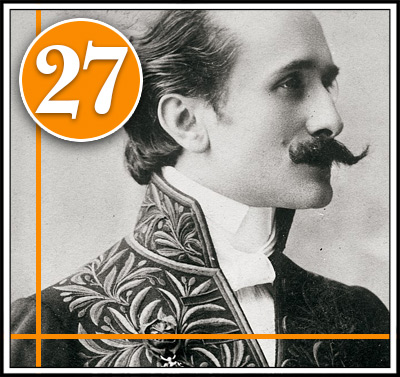

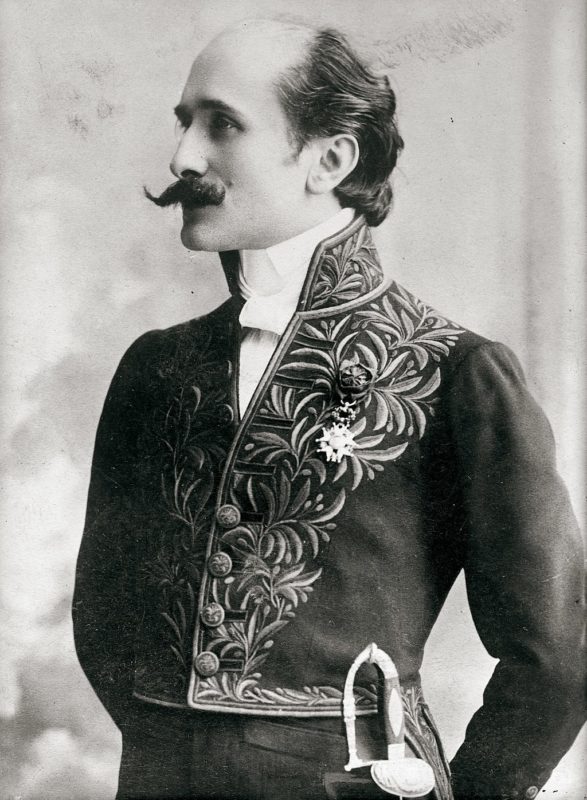

A Study of Edmond Rostand’s Personality and Methods of Writing

By Cleveland Moffett

From McClure’s, Vol 14, 1900

AND now, in this period of young great men, steps forth another to join the growing company of those become famous before thirty. On the morning of December 29, 1897, Edmond Rostand, aged twenty seven, and little enough known up to that time, awoke in Paris to find all things at his feet: this because a five-act play of his in verse, “Cyrano de Bergerac,” had been received the night before at the Porte St. Martin Theater with mad demonstrations. The play marked a new era in the drama, some said; it certainly ushered in a stage triumph such as Victor Hugo scarcely knew, a greater triumph than the English stage had seen for an even century. Here are some facts: To begin with, a run in Paris of 400 performances and Coquelin scarcely started in the rôle; an amazing success in America, with ten rival companies playing to packed houses in spite of bad translations (all but one); Germans delighted with Ludwig Fulda’s exquisite version; Spaniards wild over their version; ten performances in St. Petersburg, which is counted a memorable thing in Russia; Norway and Sweden playing “Cyrano’; Denmark playing “Cyrano’; half-forgotten little countries down Servia way playing “Cyrano” in queer tongues like the Croatian; and critics for once led meekly by the noses after “Cyrano,” the venerable autocrat “Uncle’” Sarcey (since deceased) heading the procession. Only one judgment, then, from public and press in all countries rated civilized—“Cyrano” is a masterpiece.

And hear what “Cyrano’ himself has to say in this matter, the flesh-and-blood realization of Rostand’s ideal, the elder Coquelin, one who knows the stage and its traditions in and out—a veteran of the Comédie Française, actor-manager at present in his own theater, the Porte St.-Martin, the strongest figure of a man on the stage of France today. Here is the little narrative of personal experience that I got from him one morning in his pleasant Paris home overlooking Napoleon’s arch:

And hear what “Cyrano’ himself has to say in this matter, the flesh-and-blood realization of Rostand’s ideal, the elder Coquelin, one who knows the stage and its traditions in and out—a veteran of the Comédie Française, actor-manager at present in his own theater, the Porte St.-Martin, the strongest figure of a man on the stage of France today. Here is the little narrative of personal experience that I got from him one morning in his pleasant Paris home overlooking Napoleon’s arch:

“It was in the fall of 1894, I think, that I met Rostand first. I chanced to be at the house of Madame Sarah Bernhardt one day while Rostand was reading to her his ‘Princesse Lointaine,” produced later at the Renaissance. I was present only as a friend, but was greatly struck by the beauty of the lines and the high artistic quality of the author’s rendering. Bernhardt was stirred to tears, in fact was ill in bed for two days afterwards from the emotion.

“After the reading I was presented to Rostand, and told him how sincerely I admired his work. Then, just as I was going, he said: “I should like to write something for you. I think I have a good idea.’ Now, see how completely I had come under his spell, for at once I said that whatever he would write for me, on what ever subject, at what ever time, I would accept without question or reservation, and put on the stage at my own theater: rather a remarkable pledge, seeing that our acquaintance dated from about ten minutes back; but I meant exactly what I said.

“Some weeks later he came to me with his subject, and went over it in detail. I was pleased, and he went away. A month later he came back, and told me he had changed his mind and chosen another subject. There should be two men in love with a woman-one handsome, the other homely. The handsome man was stupid, the homely man extremely clever. These two should become friends, and the love-making go on as you know. I was delighted, and marveled that no dramatist had ever hit upon that theme. A few nights later he came into my loge, and read me the duel verses. Ah, but that made an impression on me! What words, I said to myself, what action in every line! I can hear him yet declaiming it.

“A little later he read me the famous lines where Cyrano introduces the cadets. I told him he would do a masterpiece if he kept on this way, and he did keep on. Little by little, scene by scene, he brought me the play as it grew, until finally I had it all. In the summer he withdrew to the country, at Boissy St.-Léger, where most of the writing was done, and where I went down often to pass the night and hear how things were going. Here was genius in full operation, the real thing and no mistake. He worked furiously, without restriction or moderation; he could work in no other way. Sometimes it was a delight to watch him cherishing and smoothing his verses as a fond gardener who waters the flowers he loves and gives them sun. Again he wrought out his lines in torture, like a spirit driven through hell with rest forbidden. There are men, you know, like Sardou, who can rise every day at a certain hygienic hour, work so long, and refuse to work any longer. Rostand is not of that kind.

“Another thing I soon observed was this, that the critical power in him is perhaps as remarkable as the creative power. He knows with unerring judgment when a thing is good and when it is bad. He judges his work exactly as if someone else had written it, and you may be sure when he pronounces a thing good, though it be his own, he makes no mistake.

“When “Cyrano’ went into rehearsal my wonder grew again, for here was a novice in stage-craft handling a hundred people without effort, solving difficult dramatic problems as they arose by flashes of intuition, and withal showing an understanding of technique, a sureness in his effects, that not even Sardou could surpass, and a delicacy of artistic perception surpassing any one. Yet he did it smoothly, with few words, the company outdoing themselves under him, like musicians led by a great conductor. We were in rehearsal about two months and a half, with some sixty repetitions, and during that time I never knew Rostand to be in doubt before any dramatic tangle or to make an error in judgment.

“On one point I was much troubled. It seemed to me that “Cyrano’ was too long; twenty-five hundred lines went beyond all precedent. Even ‘Ruy Blas’ is several hundred lines shorter than that, and ‘Ruy Blas ‘plays from eight o’clock to midnight. “I’m afraid it’s too long,’ I would say to Rostand. ‘We must cut something out.” “Well, what shall it be?’ he would say. ‘I don’t know,” I would answer, “but we must surely make it shorter.” Then Rostand would laugh, and agree to cut out whatever I decided could be spared. And though I spent hours over the lines searching for weak ones, and lay awake of nights saying them over, I never found one that could be spared.

“So the play was not cut, after all, and, thanks to fast marching under Rostand’s generalship, we managed to run it through in reasonable time. And had we gone on past midnight, I am sure the people would have stayed; for when were so many elements of popularity ever brought together in one play! “Cyrano’ is full of action, it stirs the noblest emotions, it is amusing, it is clever, it contains charming lyrics, a delightful love story, plenty of fighting, swagger, pathos, nonsense, what is there like it! I played through the run of 400 representations (missing only one week, when I was ill), and I can honestly say I enjoyed them all.”

In seeking knowledge of this young dramatist, it was natural to go from Coquelin to Bernhardt, for if the former has thus far had the greater play by Rostand, the latter has had three of his plays by no means of small value—“La Princesse Lointaine,” “La Samaritaine,” and “L’Aiglon.” It was at her own theater that she received me, just as she had come from a rehearsal of “Hamlet,” and she was weary from an hour’s work of the intensest kind. Yet what change of manner, what brightening of the eyes at Rostand’s name! One would think him a sovereign or demi-god. The great actress is even more ardent than Coquelin in her tribute. Rostand is admirable, he is wonderful, and she speaks of her own relations to him with a glow of gratitude. He is the master, she the willing instrument. What he writes is beyond compare, what he wishes is the law. “I thank God, monsieur, that he has let me be alive now to interpret a part, at least, of what this great genius will produce. If Rostand were to die, it would be a calamity to mankind, for he is bringing in a new period in the drama—a clean, wholesome period. If Rostand were to die, I think—why, I think I should want to die too.”

In seeking knowledge of this young dramatist, it was natural to go from Coquelin to Bernhardt, for if the former has thus far had the greater play by Rostand, the latter has had three of his plays by no means of small value—“La Princesse Lointaine,” “La Samaritaine,” and “L’Aiglon.” It was at her own theater that she received me, just as she had come from a rehearsal of “Hamlet,” and she was weary from an hour’s work of the intensest kind. Yet what change of manner, what brightening of the eyes at Rostand’s name! One would think him a sovereign or demi-god. The great actress is even more ardent than Coquelin in her tribute. Rostand is admirable, he is wonderful, and she speaks of her own relations to him with a glow of gratitude. He is the master, she the willing instrument. What he writes is beyond compare, what he wishes is the law. “I thank God, monsieur, that he has let me be alive now to interpret a part, at least, of what this great genius will produce. If Rostand were to die, it would be a calamity to mankind, for he is bringing in a new period in the drama—a clean, wholesome period. If Rostand were to die, I think—why, I think I should want to die too.”

She went on to tell of her own strong emotions in paying “La Samaritaine,” and of its effect upon the people. “The rôle exhausts me more than any I have ever interpreted, because of its spiritual intensity. You know I am a believer, as Rostand is, and the play becomes a reality to me every time I go through it. And the audience—ah, if you could only see how they crowd the theater every year at Easter-tide when we put on “La Samaritaine.’ All kinds of people come, those who never go to church, women who have done wrong, priests, children, old men. And as they listen to the simple story, they are moved to the heart, they weep, they pray. I am sure that play does more good in the world than many sermons.”

After these glimpses of Rostand at second hand, let us come now to the real man (since we may be so fortunate), and judge of him for ourselves; talk with him, too, in his own delightful hôtel in the Rue Alphonse de Neuville, not three minutes’ walk from Bernhardt’s bijou of a home.

The house forms an arc behind the point of two streets where another house stands, the two built in harmony, with happiest result. Within are wide staircases and high ceilings, and the eye travels freely from room to room between columns and draped arches and wide glass doors. On the walls are tapestries and somber paintings, under foot soft rugs and polished wood, while the spacious halls and salons are furnished with pieces to delight a collector. Here, then, is fame met with fortune, youth with genius, and into the bargain, I am told, this most favored man has a lovely and accomplished wife. As for the money, Rostand comes of a wealthy family, and his own earnings have, of course, been large.

The house forms an arc behind the point of two streets where another house stands, the two built in harmony, with happiest result. Within are wide staircases and high ceilings, and the eye travels freely from room to room between columns and draped arches and wide glass doors. On the walls are tapestries and somber paintings, under foot soft rugs and polished wood, while the spacious halls and salons are furnished with pieces to delight a collector. Here, then, is fame met with fortune, youth with genius, and into the bargain, I am told, this most favored man has a lovely and accomplished wife. As for the money, Rostand comes of a wealthy family, and his own earnings have, of course, been large.

It is of interest sometimes to recall little things that strike one, on first meeting a person of importance. In the case of Rostand, I noticed that he came into the room walking stiff and straight, with a certain dapper dignity, and that his hands were extremely white, with rings on the fingers, a fine sapphire among them. Then I saw that he was small and slender, very pale, and quite bald for a man of twenty-nine; also that he wore a reddish, bristling mustache, and the Legion of Honor ribbon in his coat. In his right eye was a single staring glass that fixed you rather coldly, and added to his general impassiveness. You felt that here was a man to keep his reserve until he saw reason for leaving it and make sure a person was worth talking to before he said much. This self-withholding attitude is, no doubt, part of the armor he has learned to wear since his great success came; for a whole city, and that Paris, has flung itself at his head, with women pursuing him and men pursuing him, and all sorts of people lying in wait for him on all sorts of pretexts, the only certainty being that they will waste his time. Lately, people have taken to calling him a savage, and they tell exaggerated stories of how he never answers letters and seldom receives visitors, and is often brusque and rude. It is said, for instance, and with truth, I believe, that he recently declined the invitation of a certain continental royalty to be guest of honor at a special performance of “Cyrano.”

I asked M. Rostand about his first literary work, and he went back with pride to his twentieth year, when his maiden book of poems, “Les Musardises,” was reviewed in the “Revue Bleue’’ with highest commendation, hailed, in fact, as “the most brilliant poetic début since Alfred de Musset published his “Contes d’Espagne.’” The writer of this was laughed at then, but he is not laughed at now. I asked Rostand what authors he had admired most from his youth, and he answered without hesitation: Shakespeare, Dickens, and Victor Hugo. Could he read Dickens in English? No, unfortunately. Had he been in England? Not to know anything about it, only ten days at a London hotel. Had he traveled in other countries? No, he had stayed at home.

I asked him about sports and manly exercises. Was he at all like Cyrano in his own tastes? Was he fond of fencing or sword practice? He was not, thought it too fatiguing. Did he go in for horseback-riding? No, that was also too fatiguing. Then his love of excitement and stirring deeds was more of the head than of the body? Yes, he supposed it was.

Coming to the chief purpose of my visit, I was glad to learn that the play “Cyrano de Bergerac” was a fruit of slow ripening. Already in his student days at Stanislas College, Paris, and in vacations at Marseilles (his home), it had been in his mind to make a play where the hero’s nobility of soul should be offset by some physical defect. And he hit upon Cyrano in the histories (a real hero who had lived), caught at him, in fact, as the very type of what he wanted. Then the love theme grew accidentally from a real happening one summer while he was at the sea-side. There was a young fellow, a friend of the Rostands, deeply in love with a very attractive girl. And she was coy, while he was rather clumsy in his wooing. So in good nature and to amuse himself, Rostand helped out the unsuccessful swain with hints and counsels. Do this, he would say; talk to her about that. Give her certain flowers. Speak of such a poet and such a musician. All this based on a knowledge of the young lady’s tastes and aptitudes. And presently Rostand was rewarded by hearing from his wife that the girl had declared the young man much less of a fool than she had thought him. In fact, from that moment things went smoothly for these two, and the affair began to take literary form in Rostand’s mind.

As to the actual writing of the play, it was as nearly as may be a work of inspiration. It was not done by any rule. There were no fixed hours for it, no thought of duty. Rostand wrote early or late, much or little, precisely as he pleased, and never when he did not please; in short, he worked when he loved his work, and as he generally loved it, he worked well in the main.

“I never force my pen,” he told me. “If I feel that my vein is tiring, yet might run on for an hour or two, I stop and let it rest. And I assure you it has happened to me many times to look with wonder, as if it were a miracle, at words and thoughts that have come to me.’’

Not at all a man this to say, with the business-like positiveness of certain authors: “I write so many words an hour, sir, so many before dinner, so many after dinner; in a week I do so many pages, in a month so many chapters; and here is my time-table of novels for three years ahead, if you care to glance it over.”

I asked Rostand if I might see a page of his “Cyrano” manuscript, and he shook his head with a rueful smile. “There is no manuscript of “Cyrano’ to show you,” he said; “I only wish there were. If I had known what demand there would be for it, I should have taken good care not to throw it in the waste-paper basket. You see, I like things neat—in fact, I hate things when they’re not neat; so a page with lines scratched out and words written in distresses me. I always copy it over in a clean hand, or get my wife to copy it, and then the old page is destroyed. This process of making fresh changes and fresh copies went on with “Cyrano’ until the play was finished, when I had it typewritten. And all the earlier drafts were thrown away except some fragments of rôles that I gave to Coquelin and which he has preserved. These are all that remain of what I wrote with my own hand. It is only the great success that gives them value, and who could have foreseen that?’’’

Rostand often goes to the play for the pleasure of it and to study effects. His own “Cyrano’ he saw no less than sixty times in the first hundred performances, then found that enough, and scarcely went again until the four-hundredth, the last of the great run. And in the whole time he made no speech, nor ever came before the curtain, though the audience cheered and shouted for full twenty minutes after the première, call ing repeatedly for the author, until M. Coquelin had to tell them he had left the theater, though he was actually in hiding under the stage at the time.

He is unwearying in attendance at rehearsals, and first, last, and always dominates the situation. Even Bernhardt bows to his authority. He listens willingly to suggestions from the actors (though these are rarely made), but never allows the slightest change without his full approval. Of his own accord, both during rehearsals and after, he makes many slight modifications as he sees room for improvement, and is his own severest critic.

“On one point I stand firm,” he said to me, “I will have no line or situation in any play of mine that is not wholly my own. If one of my company were to give me a splendid climax, just what I was seeking, I would not use it; for if I did, I should no longer be the master, and that I must be.”

Not only does he give the actors detailed directions for their rôles, for tone and gesture and facial expression, but he actually does the thing for them, acts the rôle out as he wants it done, and changes from part to part with astonishing ease. Bernhardt says he is a finished actor, and Rostand told me himself that it would delight him to act on occasions in his own plays were not the usage against it.

“As it is,” he said, “I do act them all many times over and through every rôle. When I have written a scene, I rehearse it to myself. I swing my arms and stamp about, declaiming the lines in different ways, with cutting out and putting in, until they come right from my lips to my ear, until they fit and feel comfortable, like a well-made coat. Then I try them on my wife or my friends.”

“Have you any idea how long it took you to write ‘Cyrano’?” –

“I gave only a few months to the actual writing, but years to perfecting the conception. Then I wrote it skipping about from act to act, a bit here and a bit there, with out any order or system. Besides that, while I was writing ‘Cyrano,’ I was working at intervals on other things. You See, I always have two or three plays ripening in my head at the same time.”

Rostand certainly talks modestly enough about what he has done. No doubt he knows his own value, but he seems to take it as something outside of himself, for which he deserves no especial credit. And one feels that he has known his power all along. He does not regard “Cyrano” as so much better than “La Samaritaine” or the “Princesse Lointaine.” In fact, he will tell you frankly of merits that did not get their due in the very first piece he ever wrote for the stage. “I was just out of college,” he said, “and one day I showed M. Jules Clare tie, of the Comédie Française, a one-act comedy I had done. He urged me to submit it formally, and said he was sure it would be accepted. I was delighted, of course, and submitted it; but the little play was rejected, partly, I believe, because I entrusted the reading to an actor instead of doing it myself.

“Well, M. Claretie stood by me anyhow, and told me to go ahead with a three-act comedy and submit it as soon as I could. So I wrote “Les Romanesques,’ and it was accepted with special honor at the Comédie Française; and the first thing I knew, Sarcey was proclaiming me “the modern Regnard,’ and I found myself booked to write light comedy all my life. But I had no intention of accepting any such narrow mission. Comedy was well enough, but I realized that comedy alone was as unsatisfactory as tragedy alone or melodrama alone. What I wanted to study and depict was life. So I wrote a play forth with, “La Princesse Lointaine,” which was delicate and sad and tender-in fact, as far as possible from light comedy—and I let the critics reprove me as they pleased (although it often hurt). Yes, I knew what I was doing. And then I wrote “Cyrano,” which, I suppose, has a little of everything in it, like the world about us.” –

I asked M. Rostand if he had in mind any moral effect in writing “Cyrano.” Was there any lesson of courage and chivalry he had wished to teach.

“Only indirectly,” he said. “I have never been attracted to purpose plays or problem plays. If you build a work on some theme of passing interest, say a question of marriage law or divorce procedure, it is evident your work loses its reason for existence so soon as this question is settled. There fore, I choose rather themes made from the old eternal motives that guide our lives, for these are neither new nor old, but always the same and always diverting. The chief business of a playwright, I take it, is to entertain his public. If he does not entertain them, he will try in vain to teach them.

“Yet I recognize the responsibility of a dramatist, especially one who wields great power by reason of success. Whether he intend it or not, it is certain that his plays do teach and influence many people for good or ill. I hope I shall always keep to the purpose that has so far guided me, of set ting forth the fine and worthy in life rather than the despicable, the clean and beautiful rather than the ugly, the noble and inspiring rather than the perverted. In a broad sense, “Cyrano’ was intended as a lesson; that is, a stirring of sympathy for loyalty and chivalry and courage, just as “L’Aiglon’ [the play on which M. Rostand was at this time engaged] will, I hope, bring a national thrill for unsullied patriotism and love of country.”

“Do you ever feel that your creations are real, even while you are writing them?’’

“Not to the same extent as when I see them on the stage; but many times I have felt most keenly the emotions of my characters. I have suffered and rejoiced with them to the crowding out of actual things in my own life. I was an impossible person to live with while I was doing the pages of Cyrano’s death, there in the fifth act, and I don’t know that any real happening ever stirred me so deeply as the writing of that second act in ‘La Samaritaine,” where Jesus forgives and comforts the penitent woman.”

“Not to the same extent as when I see them on the stage; but many times I have felt most keenly the emotions of my characters. I have suffered and rejoiced with them to the crowding out of actual things in my own life. I was an impossible person to live with while I was doing the pages of Cyrano’s death, there in the fifth act, and I don’t know that any real happening ever stirred me so deeply as the writing of that second act in ‘La Samaritaine,” where Jesus forgives and comforts the penitent woman.”

After this the talk drifted into less important channels, getting finally to bicycling and amateur photography, in both of which Rostand finds diversion from his work. And with so much we may leave him, my own judgment being, after several interviews in which he talked freely, that he is a charming man, with a delightful blending of seriousness and fun, quite free from nonsense and conceit, one who is absorbed in his work, an goes at it in the most sensible way possible for a man of his temperament.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

By subscribing, you will automatically receive the latest episodes downloaded to your computer or portable device. Select your preferred subscription method above.

To subscribe via a different application: Go to your favorite podcast application or news reader and enter this URL: https://clearwaterpress.com/byline/feed/podcast/