Kit Carson’s Duel

Episode 20•

Kit Carson’s Duel

• “Gervais,” he said, “go to yonder bully, and say to him that unless his threats and boasts cease, I shall be forced to kill him.”

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Email | TuneIn | RSS

SHOW NOTES ____________

Kit Carson’s Duel

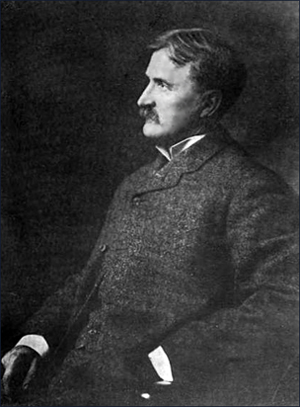

By Emerson Hough

“How much farther, Francois?” asked the leader of a little mountain cavalcade which wound its way down a broad river valley in the heart of the Rocky Mountains. “See, it is now noon, and the encampment is not yet in sight. Shall we not stop and rest?”

“How much farther, Francois?” asked the leader of a little mountain cavalcade which wound its way down a broad river valley in the heart of the Rocky Mountains. “See, it is now noon, and the encampment is not yet in sight. Shall we not stop and rest?”

The speaker was a tall, thin man, whose face, browned by the sun of the plains and mountains, none the less bore a refinement almost approaching austerity. The man accosted was leaner and browner than himself, and wore the full costume of the Western engage of the fur trade.

“Mister Parker,” he replied, “always you ask how far to the encampment. I do not know. In the mountain we do no ask how far. We push on the horse. That is all.”

“But the rendezvous–are you sure it is in this valley of the Green?”

“It is established for the month of August in the valley of the Green. Those man of the mountain, he do not disappoint. This rendezvous of the year 1835, it may be the last one for the trappers. But me, Francois Verrier, say to you that you shall see the rendezvous, also the trappers, and the traders, and the Indians–hundreds of them. My faith! They shall see for the first time the missionary to the Indian! Mister Parker, you are not the good father? Yes? You shall make some little prayers for those savages.”

The thin face of Samuel Parker brightened. This land before his view, majestic, beautiful, was as fabled and unknown as the continent of lost Atlantis. It was a wild world, a new one. He, first to answer that strange appeal from the wild Northwest,–that appeal carried by the four Nez Perces Indians, who traveled in ignorance and hope across half a continent to ask that the Book might be sent out to them by the white man,–felt now exaltation swell within his soul.

What a meeting must be this, which he had pushed forward so eagerly to discover! It was a gathering, as he had been well advised, not in the name of religion or of politics, of art or science–hardly even in the cause of commerce, although here the wild trappers and hunters, absent from one year’s end to the other in the mountains, annually met, at some appointed spot in the Rockies, those bold merchants who brought out to them stores of goods to trade for furs. The trappers’ rendezvous! He had heard of it a thousand tales distorted and unreal. Truly there was work ahead. He caught up the reins upon his horse’s neck, forgot his weariness, and resumed his way.

His followers, a score or more of horsemen and pack-train drivers, among whom rode a short sturdy young man, the future martyr-missionary, Marcus Whitman, moved on, browned, gaunt, dust-begrimed, yet cheerful.

They had traveled for perhaps a mile or so down the valley when the guide, riding abreast of his employer, suddenly pulled up his horse and signed for his companion to pause.

“Mister,” said he, “you think I know little of this land. Behold! We are have arrived this hour.”

He pointed. There, against the sky-line, on a projecting range of the mountainside which sloped down to the edge of the valley, was the figure of a mountain man, motionless, and evidently on guard.

“Yes” cried Francois, setting heels to his horse. “It is the guard of the encampment. Ride quick, my comrades!”

The train, packhorses and all, pushed forward at a gallop, which soon broke into a wild run–the proper gait in trapper custom for all who arrived at the mountain rendezvous.

As they rounded the spur of rocks which had made the watch-tower of the sentinel, the full scene burst upon their eyes. There was a wide, sweet space in the valley, made as if for the very purpose of the great rendezvous. A flat of green cottonwoods adjoined the river-bank. “Benches,” or natural terraces, of sweet grass rose along the hillside a half-mile away. Hundreds of horses, picketed or hobbled, grazed here and there. Others, favorite steeds of their masters, stood tied at the doors of lodges, in front of which rose long, tufted spears, in the heraldry of that land insignia of their owner’s rank. Teepees, a hundred and twoscore, skin tents of the savage tribes and homes also of the whites, were grouped irregularly over a space of more than half a mile. At the doors of many of these, silent Indians sat and smoked. In the wide interspaces of the village were many men, some of them dressed in brown buckskins, others clad more gaudily. These passed to and fro, some on foot, others riding furiously. Animation was in all the air.

Shouts, cries, a tumult formed of many factors filled the air. Babel of speech rose from Frenchmen, Spaniards, Canadians, English, Scotch, Irish, and American backwoodsmen, and Indians of half a dozen tribes. Horses, dogs, black-haired and blanketed women, and children of divers colors moved about continually. The gathering was heterogeneous, conglomerate, picturesque, savage.

Samuel Parker, missionary to the Oregon tribes, and now come hither to the mountain market of 1835 as knight-errant of the Gospel, pulled up his horse at the edge of the encampment and gazed in sheer amazement. His party–except Whitman, who reined in his horse at his friend’s side–passed on and joined the shouting throng. Apparently they conveyed certain news as they rode; for now out of the circling ranks of wild horsemen there swept toward the strangers a group of yelling riders.

Long ribbons and waving eagle feathers streamed from the manes and tails of their ponies. Some riders, even of the white men, wore the great war-bonnets of the northern tribes, the long crests of feathers sweeping back upon the croups of the rough-coated steeds they rode. Weapons were in the hands of all. Loud speech and many oaths were on their lips. They might well have disturbed bolder hearts than that of a peaceful missionary.

The leader of the approaching band was a man of gigantic stature, more than six inches above the six-feet mark. He was dark of hair and eye; a wide mustache swept back across his face, and his heavy, untrimmed beard, matted and sunburned at the edges, gave him an expression savage and forbidding.

Clad in the buckskin of a mountain trapper, none the less this personage affected a certain finery. A brilliant sash encircled his waist, his hat bore a wide plume. At his belt hung pistols, and in his hand was a long rifle. He pulled up his horse squatting,its nose high in air.

“How, friend!” he cried. “Or be you friend, who come thus without word to Bill Shunan’s camp?”

“Sir,” replied the missionary, “my name is Parker–Samuel Parker. I am from far New England, and am bound upon my way to Oregon. I have come aside from the Sublette Cutoff trail to be present at this rendezvous. Yourself I do not know.”

“What! Not know Bill Shunan, the bully of the Rockies, and the owner of this camp? Listen, stranger, you are treading on dangerous ground. I’ve whipped half a dozen men to-day, and driven every fighter of the rendezvous back into his lodge. They know Bill Shunan, and they show him respect, as you shall yourself.”

Samuel Parker made no reply, and found no way to move forward, even had he been sure that friends awaited him in the village. The giant went on:

“Now, what’s your business, man? You look like no trapper nor good mountain man. As for more Yankee traders, we’ve enough of them now, and more than enough. Look at their packs, laid out there, half of them not opened! The traders are robbing us mountain men at this market. Two skins they ask for a pint of sugar, if one would please his squaw. As much goes for a knife; and three skins for coffee as much as you could put in a pint cup. Powder they hold as high as gold-dust, and a blanket is worth a pair of horses. It’s robbery, and I’ll have no more of it. If Jim Bridger and Bill Williams, and their half-black Beckwourth, and Gervais, and Fraeb,and their other offscourings of old Ashley, will not rebel against such doings, then, for one, Bill Shunan is not afraid. My people were French back in old Canada. It is the French who found the Rockies, and who ought to own them! These Americans–I whip them with switches! And so I’ll whip you if you come here as a trader and give us no better measure than these others! Now, I say, who are you?”

The dark eye of the missionary lighted again with its hidden fire.

“I am a missionary,” said he, “a man of the church, a minister of the Gospel, as I would have said to you. I have come to this encampment to hold divine services among you. Red men or white, we are brethren, and we are sinners in common.” The close-shut mouth, the dull flush visible beneath the tan, the flash of the eye, all bespoke him a man not devoid of courage. Yet his speech brought only rage to the other.

“Minister!” he cried. “By all the saints, no unfrocked priest shall speak words in this camp of mine! Not even a good father of the French has been present at a rendezvous of the bully boys of the mountains; and who are you, to come intruding at the frolic of the trappers? I’ll have no sniveling Protestant here. So leave at once!”

“Sir,” said the minister, “I have ridden far, and I am not of a mind to go back.” He crowded his horse forward, the more so as he saw approaching another band of men from the encampment. He could only hope that they might be of a class not quite the same as this desperado. A moment later these riders joined the group of parleyers.

“How now, what is this?” cried out the tall man who led these newcomers. “Who’s the stranger? Does he carry news from the States?”

“Back with you, Bill Williams!” cried Shunan. “‘This but a sniveling preacher from the East, and I have told him he shall bring no psalms here.”

The freshly arrived horsemen made small reply to Shunan’s speech, but bent a curious gaze upon the stranger. The latter saw at a glance that these were no allies of the bully. Therefore he glanced toward them as if in appeal.

Without a word a half-score of them urged their horses round him, and separated him from Shunan’s party.

“What!” cried Shunan. “You dispute me? I tell you he will never see the sun again if he pushes himself into this camp. What do you mean, you puny Yankees? Do you want me to put you on your death-beds, as I have a couple of you before to-day? Back with you! For I say this man shall not come into camp!”

“Shunan,” broke in a quiet voice, “who gives you right to issue orders here?”

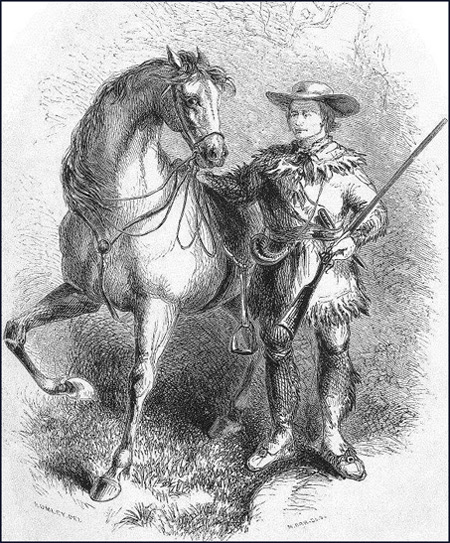

The speaker was a young man, still in his twenties; and so far from equaling in stature the giant whom he addressed, he was slight and small, not over five feet six inches in height, although of good shoulders and great depth of chest.

He sat a dark-brown horse, fully caparisoned in the Spanish fashion. His garb was of buckskin, but plain and devoid of ornamentation. A wide hat swept over his well-tanned face, and from beneath its brim there shone the steely glance of gray-blue eyes.

Shunan, dumbfounded, whirled his horse toward the speaker.

“Shunan,” repeated this man, in turn urging his own horse forward, “you’ve made trouble enough in the encampment. You shall no longer act the bully here. The stranger comes in peace, and he shall be heard here if he likes. What!” and the blue eyes flashed. “Would you issue orders at a meeting of the free men of the mountains–the very place in all the world where every man who comes in friendship is made welcome? This is our country. This is our encampment. The law of what is right shall govern here; and I take it upon myself to say this to you!”

Silence fell upon all who heard these words. The last speaker raised his hand as Parker would have spoken. The friends of the young man now pressed closer about him. He did not give back, but urged his mount still forward, until it breasted the cream-colored horse which Shunan rode. The bully, half-sobered from his potations by this stern situation, did not himself give back.

“Who are you?” he cried. “By what right do you question Bill Shunan? Would you be the next to be whipped with switches? There is but one end to this, boy! Are you ready for it?”

“Have I ever been found unready?” asked the young man, quietly. “I say again, this land is free. The stranger shall have meat and robes at my lodge, and if he will speak, he shall have his say.”

In a rage Shunan spurred forward, his hand uplifted; yet the brown horse and its rider receded not an inch. The issue was joined. There must now be combat!

“Not here!” cried old Bill Williams, suddenly. “Wait! Back to the camp with you all, and there let it be decided proper!”

This speech met with sudden approval upon both sides. An instant later the missionary’s horse was swept forward in a rush which carried both parties, intermingled, deep into the center of the tented village.

Well toward the middle of the encampment there was a large and irregular space left unoccupied, a sort of plaza, devoted to common use, and employed as meeting-ground in the trading operations of the market, or the jollifications, which occupied far more of the time. As the riders came into this open space Shunan and his party drew off to the right. His antagonist sought out his lodge upon the opposite side. He was followed here by several of his warmer friends, Williams, Bridger, Fraeb, other men of the mountains at one time known throughout the length and breadth of the West.

“Sir,” said the young man, turning toward Samuel Parker, “get you down, and come within my house. Perhaps by this time you are used to such. We bid you welcome. I shall return to you soon, after I have settled this matter which has come up between me and yonder ruffian.”

“I beseech you!” cried the missionary, reaching out an imploring hand. “What is it you would do? Surely you do not mean–you would not engage in combat with this man–you do not mean bloodshed? This–on my account–no, no! Let me go.”

The quiet man whom he thus accosted made no answer at first, but pushed back the hat from his brow and gazed upon the newcomer with a kindly eye.

“There is but one way,” said he. “Bill, see to it that our friend has good treatment here.” The man addressed took Parker by the arm and thrust him gently within the lodge.

The young man now summoned another friend. “Gervais,” he said, “go to yonder bully, and say to him that unless his threats and boasts cease, I shall be forced to kill him. Our bullets should be for our enemies, but Shunan has made trouble enough; and he must go to his lodge or meet me, man to man.”

“Are ye ready for him, boy?” asked Gervais. “How is the shoulder where you caught the Blackfoot bullet last fall? Can you handle the rifle?”

“I’ll not trust the shoulder,” was the reply, “and will not risk the rifle.” He drew a pistol from his belt and looked at the priming of the pan. “One shot,” said he; “and it must do.”

“But he’ll use his rifle.”

“Very well. Go to him and say that I shall come mounted, like himself, and he may be armed as he likes. No man is my superior on horse or with any weapon. Moreover, you shall see that I do not seek so much to kill him as to end his boasting, and to restore the law in this camp.”

Gervais sprang upon his horse and was off, calling out to others, who drew near, the instructions which he had received. He approached Shunan, who was now urging his horse round and round the open space of the village, shouting defiance and uttering foul reproaches for his antagonist, whom he announced himself eager to meet. Gervais delivered his message.

The bully continued to crowd his horse back and forth, pulling it up so sharply that it was thrown upon its haunches now and again in mid-career. He waved his long rifle over his head, and issued a general challenge to all within reach of his voice.

At this moment there rode out from the farther side of the circle the champion of law and order. The horse which he bestrode came on strongly and lightly, its head up. The rider had stripped off all his accouterments, and rode a buckskin pad-saddle, Indian fashion. About his waist was a belt, which bore no weapons. His long rifle, at which weapon he had no master, did not rest upon the saddle front. His hat was gone, and a handkerchief bound back his long light hair. He rode forward lightly, easily, in confidence.

Shunan, yelling, wildly, charged at once upon him.

The young man sat erect; but when Shunan was still a score of yards away, the brown horse leaped aside, its rider lying along its neck as an Indian might have done, and swept round and to the rear of Shunan.

The bully, fumbling with his piece, endeavored to follow. Then he saw the pistol barrel pointing under the neck of the brown horse, and cold terror smote his soul.

The two swept past again at full gallop, Shunan still not quite master of his horse and weapon at the same time, for the long-barreled, muzzle-loading rifle was difficult to manage from the back of a plunging horse. They wheeled and passed yet again; but this time, as they turned, they headed directly toward each other at a steady pace.

The spectators knew that in an instant the issue would be decided.

Shunan jerked up his horse and threw his rifle sharply to his face. His antagonist made no attempt to swerve, but instead spurred forward sharply. The brown horse sprang breast to breast with the cream-colored mustang. The two men were within arm’s length. At this minute there rang out two reports, almost at the same instant. The horses sprang apart.

The slighter man was still sitting erect. He swept his hand hastily across his temple, where he felt a stinging burn. Shunan, dazed, sat his horse for an instant, but his rifle dropped to the ground; and as his horse sprang forward, he himself fell, and so lay, one arm hanging limp and the other raised in the sign of surrender.

The duel was over. The late friends of Shunan joined the riders who now crowded into the open space from the opposite sides of the arena.

“Did he touch you, boy?” cried old Bill Williams.

“No, though he meant it well enough. See, there’s a twist of hair gone from the side of my head.”

“He got your bullet through the hand and wrist,” said Williams, as they turned away. “His right arm’s done for, for a while. You were a bit the first with your fire, my son.”

“I know it, and I knew I had need to be. I fired at his hand, and knew I must be a shade the first. I knew if I held true, his aim would be thrown out.”

As he spoke, he dismounted at the door of his own lodge. There Samuel Parker met him, and cried, “Is it over? Is any one hurt? Has there been murder done?”

“There, there, friend,” said old Bill Williams, gently, “you bring here still your Yankee way of speech. Besides, it is no murder unless someone is killed, and yonder bully Shunan will only have a sore hand for a month or so. ‘Twas a lesson that was well needed for him. See now, the camp is quiet already. Men and women may venture out-of-doors in peace and comfort. ‘Tis but the law of the mountains you have seen, man.”

“And as for the law of the Gospel,” interrupted Gervais, “they shall have that this night round the fire, if you wish to speak.”

The minister gazed from one to the other with emotions new to him.

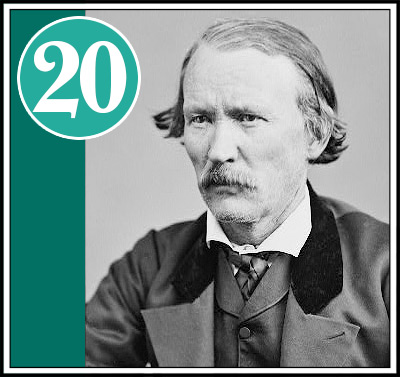

“And you, sir,” he said, extending his hand to the young man who had thus stoutly championed him, “who are you? Whom shall I thank for this strange act–for this strange justice of the mountains, as you call it?”

The bronzed men who stood or sat their horses near at hand gazed from one to another, smiling, At last old Bill Williams broke out into a laugh.

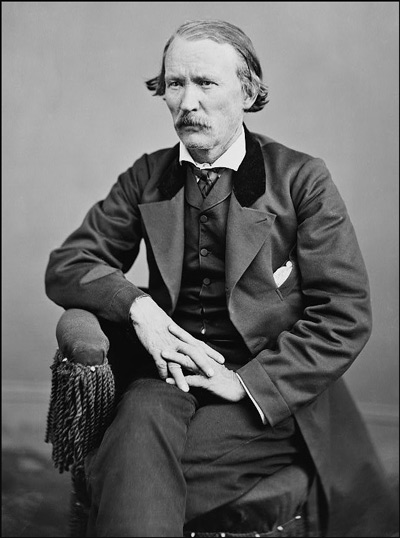

“Man,” cried he, “’tis easily seen you’re fresh from the States! What, not know the best man in all the Rockies? There is but one could have done this deed so well. We have few courts here, but whenever we’ve needed a sheriff of our own we’ve had one, and here he is. So you did not know Kit Carson!”

Kit Carson

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

By subscribing, you will automatically receive the latest episodes downloaded to your computer or portable device. Select your preferred subscription method above.

To subscribe via a different application: Go to your favorite podcast application or news reader and enter this URL: https://clearwaterpress.com/byline/feed/podcast/