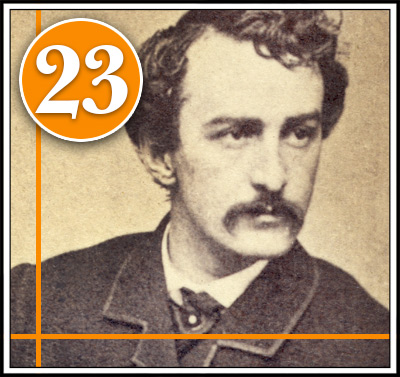

The Capture, Death and Burial of John Wilkes Booth

Episode 23•

The Capture, Death and Burial of John Wilkes Booth

• Even in his deep distress Booth had not forgotten to be theatrical.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Email | TuneIn | RSS

SHOW NOTES ____________

The Capture, Death and Burial of John Wilkes Booth

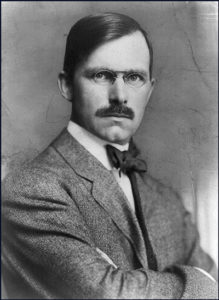

By Ray Stannard Baker

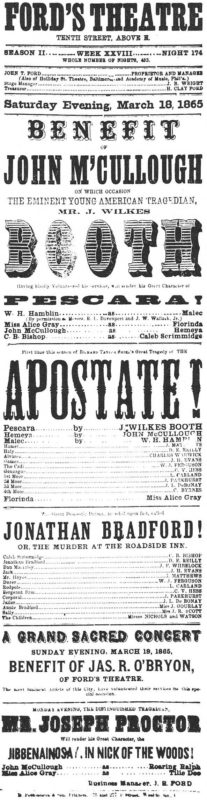

PRESIDENT LINCOLN was shot a few minutes after ten o’clock, Friday evening, April 14, 1865.

The conspirators could not have chosen a more favorable occasion for their bloody work. Washington and the North were in a paroxysm of rejoicing over the surrender of Lee and the close of a long and bloody war. The rigor of military restrictions was in some degree relaxed, and the highways of travel north and south were rapidly opening. Everywhere the air was filled with the spirit of disorganization consequent on the mustering out of armed men and the return of the soldier to his plow-handle. Even the President of the United States, weary of tedious cabinet meetings, had laid aside his arduous duties on that fateful Friday evening, to seek much needed rest at the theater.

No doubt Booth and his accomplices were conscious of this general relaxation, and calculated on it to assist them in their escape when the plotted deed in Washington was done. Certain it is that if the military cordon had been drawn as closely as it was while active hostilities were in progress, the chief assassin and his assistant never would have thundered past the sentinel on the navy-yard bridge and escaped into the yet hostile South. And compelled to remain within the confines of Washington, their capture by the police doubtless would have been a question of only a few hours.

No doubt Booth and his accomplices were conscious of this general relaxation, and calculated on it to assist them in their escape when the plotted deed in Washington was done. Certain it is that if the military cordon had been drawn as closely as it was while active hostilities were in progress, the chief assassin and his assistant never would have thundered past the sentinel on the navy-yard bridge and escaped into the yet hostile South. And compelled to remain within the confines of Washington, their capture by the police doubtless would have been a question of only a few hours.

As soon as the news of the assassination reached the War Department, thousands of soldiers, policemen, and detectives were dispatched to guard every possible avenue of escape, with orders to arrest every person who sought under any pretext to leave Washington. The Navy Department sent numberless tugs, steamboats, and even ships of war to patrol the Potomac, in the hope of preventing the flight of the assassins by boat. Before the morning of the 15th the lines were so thoroughly established that the shrewdest spy would have found difficulty in creeping through them without being captured. But at that late hour it was all to no purpose; Booth was miles away.

In this emergency, Secretary of War Stanton turned to the vice bureau, a branch of the department which was under his immediate direction and control. Colonel Lafayette C. Baker (afterwards General), its chief, was in New York city making plans for the capture of a band of bounty-jumpers then operating in the North. Mr. Stanton telegraphed him in the following words:

April 15, 3.20

COLONEL L.C. BAKER:

Come here immediately and see if you can find the murderer of the President.

EDWIN M. STANTON,

Secretary of War.

Early the next morning Colonel Baker reached Washington. He was accompanied by his cousin, Lieutenant L. B. Baker, a member of the bureau, who recently had been mustered out of the First District of Columbia cavalry. They went at once to the office of the War Department, and, after a conference with Secretary Stanton, began the search for the murderers of the President.

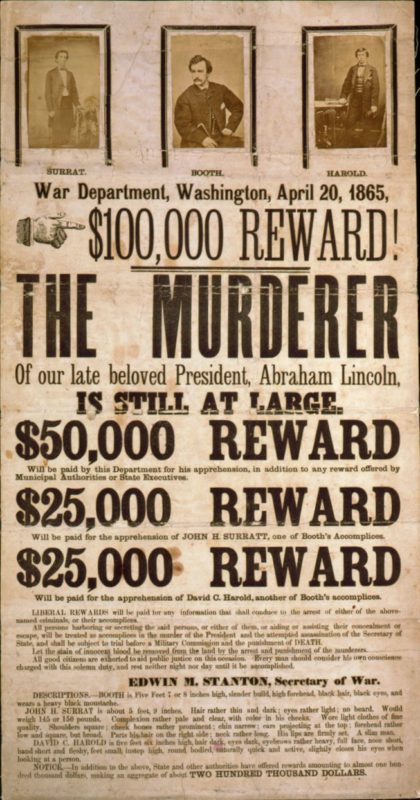

Up to this time the confusion had been so great that few of the ordinary detective measures for the apprehension of criminals had been employed. No rewards had been offered, little or no attempt had been made to collect and analyze the clues in the furtherance of a systematic search, and the pursuit was wholly without a directing leadership. Colonel Baker’s first step was the publication over his own name of a handbill offering $30,000 reward for the capture of the fugitives.

Twenty thousand dollars of this amount was subscribed by the city of Washington, and the other $10,000 Colonel Baker offered on his own account, as authorized by the War Department. To this handbill minute descriptions of Booth and the unknown person who attempted the assassination of Secretary Seward were appended. Hardly had the bills been posted when the United States Government authorized the publication of additional rewards to the amount of $100,000 for the capture of Booth, Surratt, and Herold, Surratt at that time being suspected of direct complicity in the assassination.

Three states increased this sum by $25,000 each, and many individuals and companies, shocked by the awful atrocity of the crime, offered rewards in varying amounts. Fabulous stories were told of the wealth which the assassin’s captor would receive, the sums being placed anywhere from $500,000 to $1,000,000.

This prospect of winning a fortune at once sent hundreds of detectives, recently discharged Union officers and soldiers, and a vast host of mere adventurers—the flotsam of Washington—into the field, and the whole of southern Maryland and eastern Virginia was scoured and ransacked until it seemed as if a jackrabbit could not have escaped. And yet, at the end of ten days, the assassins were still at large.

Booth was accompanied in his flight by a callow, stage-struck youth named David C. Herold, who was bound to the older man by the ties of a marvelous personal magnetism which the actor exercised as a part of his art. Two hours after the assassination the fugitives reached Mrs. Surratt’s tavern, where Herold secured a carbine, two flasks of whisky, and a field-glass.

They imparted the information with some show of pride that they had just killed the President of the United States. By this time Booth’s broken leg had begun to give him excruciating pain, and the two rode without delay to the house of Dr. Mudd, a Southern sympathizer of the most pronounced type. Here the assassin’s leg was set and splinted, for lack of better material, with bits of an old cigar-box. Rude crutches were whittled out by a friend of Dr. Mudd’s, and on the following day Booth and his deluded follower rode on to the southward.

For more than a week they were hidden in a swamp near Port Tobacco by Samuel Cox and Thomas Brown, both of whom were stanch Confederates. Here they were compelled to kill their horses for fear that a whinny might reveal their presence to their eager pursuers. After many attempts Brown was able to send the fugitives across the river in a little boat, for which Booth $300. Once in Virginia, and among Southerners, Booth felt that they would be safe; but in this supposition he was sorely disappointed. At least one prominent Confederate treated them as murderers and outcasts, and they were compelled to accept the help of negroes and to skulk and cower under assumed names.

In beginning his search for the assassins, Colonel Baker proceeded on the theory that Jefferson Davis and the whole Confederate cabinet were involved in the plot, and that Booth, Atzerodt, Payne, Surratt, Herold, and the others were mere tools in the hands of more skilled conspirators.

He therefore detailed Lieutenant Baker to procure, for the purpose of future identification , photographs of John H. Surratt, John Wilkes Booth, Jefferson Davis, George N. Sanders, Beverly Tucker, Jacob Thompson, William C. Cleary, Clement C. Clay, George Harper, George Young, “and others unknown,” all of whom were charged with being conspirators.

Later Lieutenant Baker, with half a dozen active men to help him, was sent into lower Maryland to distribute the handbills describing Booth, Herold, and Surratt, and to exhibit the pictures of the fugitives wherever possible. Under instructions from Colonel Baker, they also made a search for clues, but they found themselves harassed and thwarted at every turn by private detectives and soldiers who tried to throw them off the trail in the hope of following it successfully themselves.

On their return to Washington, Lieutenant Baker gave it as his opinion to his chief that Booth and his companion or companions had not gone south at all, but had taken some other direction, probably toward Philadelphia, where it was known that Booth had several warm friends.

“No, sir,” was Colonel Baker’s answer, “you are mistaken. There is no place of safety for them on earth except among their friends in the still rebellious South.” Acting on this belief, Colonel Baker sent Theodore Woodall, one of the detectives, into lower Maryland, accompanied by an expert telegrapher named Beckwith, who was to attach his instrument to the wires at any convenient point and report frequently to the headquarters at Washington. These men had been out less than two days when they discovered a voluble negro who told them quite promptly that two men answering to the description of Booth and Herold had crossed the Potomac below Port Tobacco on Saturday night (April 22nd) in a fishing-boat.

This evidence, which had already been spurned by a company of troops, was regarded as of so much importance, that the negro was hurried to Washington by the next boat, where Colonel Baker questioned him closely, afterward showing him a large number of photographs.

He at once selected the pictures of Booth and Herold as being the persons whom he had seen in the boat. Colonel Baker decided that the clue was of the first importance, and, after a hurried conference with Secretary Stanton, he sent a request to General Hancock for a detachment of cavalry to guard his men in the pursuit. Lieutenant Baker was then ordered to the quartermaster department to make arrangements for transportation down the Potomac.

On his return he was informed that he and E. J. Conger, another detective, were to have charge of the party. The three men then held a conference in which the chief fully explained his theory of the whereabouts of Booth and his accomplice.

Half an hour later Lieutenant Edward P. Doherty of the Sixteenth New York cavalry, with twenty-five men, Sergeant Boston Corbett second in command, reported to Colonel Baker for duty. He was directed to go with Lieutenant Baker and Conger wherever they might order, and to protect them to the extent of his ability. Without waiting even to secure a sufficient supply of rations, Lieutenant Baker and his men galloped down to the Sixth Street dock, where they were hurried on board the government tug “John S. Ide.”

It was a little after three o’clock in the afternoon of Monday, April 24th, when the expedition started. Seven hours later the tug reached Belle Plaine landing. At this point there is a sharp bend in the river, and Colonel Baker had advised his men to scour the strip of country stretching between it and the Rappahannock.

On disembarking Baker and Conger rode cautiously ahead into the dark, directing Lieutenant Doherty and his detachment to follow within hailing distance. The country was familiar to both of the leaders of the expedition, and at the homes of the more prominent Confederates they stopped to make inquiries, assuming the names of well=known blockade-runners and mail-carriers.

“We are being pursued by the Yanks,” they said; “and in crossing the river we have become separated from two of our party, one of whom is lame. Have you seen them?”

All night long this kind of work, interspersed with much hard riding, was continued. But although the Confederates invariably expressed their sympathy, it was evident that they knew nothing of the fugitives.

At dawn the cavalrymen threw off their disguises, and halted an hour for rest and refreshment. Again in their saddles they struck across the country in the direction of Port Conway, a little town on the Rappahannock about twenty-two miles below Fredericksburg. Between two and. three o’clock in the afternoon they drew rein near a planter’s house half a mile distant from the town, and ordered dinner and feed for the horses. Conger, who was suffering from an old wound, was now nearly exhausted from the long, hot, and dusty ride, and he and all of the other members of the party except Baker and one of the men—a corporal==dropped down at the roadside to rest.

Baker feared that the presence of the searching party might give warning to Booth and his companion should they be hiding anywhere in the neighborhood. He therefore pushed on ahead to the bank of the Rappahannock. Here, dozing in front of his little cottage in the sunshine, Baker found a fisherman-ferryman whose name was Rollins. He asked him if he had seen a lame man cross the river within the past few days. Yes, he had, and there was another man with him. In fact, Rollins said that he bad ferried them across the river. Instantly Baker drew out his photographs, and Rollins pointed without the least hesitation to the pictures of Booth and Herold.

“There are the men,” he said, nodding the loading was done with the greatest head; “there are the men, only this one”—pointing to Booth’s picture—“had no mustache.”

It was with a thrill of intense satisfaction that Baker heard these words. He was now positive that he, of all the hundreds of detectives and soldiers who were swarming the country, was on the right trail. But not a moment was to be lost. Even now the objects of their search might be riding far into the land of the rebels.

Baker sent the corporal back with of the cavalrymen to come up without delay. After he was gone Rollins explained that the two men—who could be none other than Booth and Herold—had hired him to ferry them across the river on the previous afternoon. Just before starting three men had ridden up and greeted the fugitives, afterward accompanying them across the river. In response to close questioning Rollins admitted that he knew the three men well; that they were Major M. B. Ruggles, Captain Willy Jett, and Lieutenant Bainbridge, who had fought during the war with Mosby’s guerrillas.

“Do you know where they went?” — Baker pressed the question.

“Waal,” drawled the fisherman, “this Captain Jett has a ladylove over at Bowling Green, and I reckon he went over there.”

He further explained that Bowling Green was about fifteen miles to the southwest, and that it had a big hotel which would make a good hiding place for a wounded man. As the cavalry came up Baker told Rollins that he would have to accompany them as a guide until they reached Bowling Green. To this Rollins objected on the ground that he would incur the hatred of his neighbors, none of whom had favored the Union cause.

“But you might make me your prisoner,” he said in his slow drawl; “then I would have to go.”

Baker felt the necessity of exercising the greatest energy in the pursuit if the fugitives were to be snatched from the shelter country. Rollins’s ferryboat was old and shaky, and although the loading was done with the greatest despatch, it took three trips to get the detachment across the river. About sundown the actual march for Bowling Green was begun.

As the horses sweltered up the crooked, sandy road from the river, Baker and Conger, who were riding ahead, saw two horsemen standing as motionless as sentinels on the top of the hill, their dark forms silhouetted in black against the sky. They seemed much interested in the movements of the cavalrymen. Baker and Conger at once suspected them of being Booth’s friends, who had, in some way, received information of the approach of a searching-party.

Baker signaled the horsemen to wait for a parley, but instead of stopping they at once put spurs to their horses and galloped up the road. Conger and Baker gave chase, bent to the necks of their horses and riding at full speed; but just as they were overhauling them, the two horsemen dashed into a blind trail leading from the main road into a dark pine forest. The pursuers drew rein on their winded horses, and, after consultation, decided not to follow further, but to reach Bowling Green as promptly as possible.

These men, as they afterward learned, were Bainbridge and Herold; and Booth at that moment was less than half a mile away, lying on the grass in front of the Garrett house. Indeed, he saw his pursuers distinctly as they passed his hiding place, and commented on their dusty and saddleworn appearance. But they believed him to be in Bowling Green, fifteen miles away, and so they pushed on, leaving behind them the very man they so much desired to see.

It was near midnight when the party clattered into Bowling Green, and with hardly a spoken command, surrounded the dark, rambling old hotel. Baker stepped boldly to the front door, while Conger strode to the rear, from whence came the dismal barking of a dog. Presently a light flickered on the fanlight, and some one opened the door a crack and inquired, in a frightened, feminine voice, what was wanted. Baker thrust his toe inside, flung the door wide open, and was confronted by a woman.

At this moment Conger came through from the back way, led by a stammering negro. The woman admitted at once that there was a Confederate cavalryman sleeping in her house, and she promptly pointed out the room. Baker and Conger, candle in hand, at once entered. Captain Jett sat up, staring at them.

“What do you want?” he asked.

“We want you,” answered Conger; “you took Booth across the river, and you know where he is.”

“You are mistaken in your man,” he replied, crawling out of bed.

“You lie,” roared Conger, springing forward, his pistol clicking close to Jett’s head.

By this time the cavalrymen were crowding into the room, and Jett saw the candlelight glinting on their brass buttons and on their drawn revolvers.

“Upon honor as a gentleman,” he said, paling, “I will tell you all I know if you will shield me from complicity in the whole matter.”

“Yes, if we get Booth,” responded Conger.

“Booth is at the Garrett house, three miles this side of Port Conway,” he said; “if you came that way you may have frightened him off, for you must have passed the place.”

In less than thirty minutes the pursuing party was doubling back over the road by which it had just come, bearing Jett with it as a prisoner. His bridle reins were fastened to the men on each side of him, in the fear that he would make a dash to escape and alarm Booth and Herold.

It was a black night, no moon, no stars, and the dust rose in choking clouds. For two days the men had eaten little and slept less, and they were so worn out that they could hardly sit their jaded horses. And yet they plunged and stumbled onward through the darkness, over fifteen miles of meandering country road, reaching Garrett’s farm at half past three o’clock in the morning of April 26th.

Like many other Southern places, Garrett’s house stood far back from the road, with a bridle gate at the end of a long lane. So exhausted were the cavalrymen, that some of them dropped down in the sand where their horses stopped and had to be kicked into wakefulness. Rollins and Jett were placed under guard, and Baker and Conger made a dash up the lane, some of the cavalrymen following.

Garrett’s house was an old-fashioned Southern mansion, somewhat dilapidated, with a wide, hospitable piazza reaching its full length in front, and barns and tobacco houses looming big and dark apart. Baker leaped from his horse to the steps, and thundered on the door. A moment later a window close at hand was cautiously raised, and a man thrust his head out. Before he could say a word Baker seized him by the arm.

“Open the door; be quick about it.”

The old man tremblingly complied, and Baker slipped inside, closing the door behind him. A candle was quickly lighted, and then Baker demanded of Garrett to reveal the hiding-place of the two men who had been staying in his house.

“They’re gone to the woods,” he said, paling and beginning to tremble.

Baker thrust his revolver into the old man’s face. “Don’t tell me that,” he said; “they are here.”

Conger now came in with young Garrett.

“Don’t injure father,” said the young man; “I will tell you all about it. The men did go to the woods last evening when some cavalry went by, but they came back and wanted us to take them over to Louisa Court House. We said we could not leave home before morning, if at all. We were becoming suspicious of them, and father told them they could not stay with us–”

“Where are they now?” interrupted Baker.

“In the barn; my brother locked them in for fear they would steal the horses. He is now keeping watch in the corn crib.”

It was plain that the Garretts did not know the identity of the men who had been imposing on their hospitality. Consequently, Baker asked no more questions, but taking young Garrett’s arm, he made a dash toward the barn.

Conger ordered the cavalrymen to follow, and formed them in such positions around the barn that no one could escape. By this time the soldiers had found the boy in the crib, and had brought him up with the key. Baker unlocked the door, and told young Garrett that, inasmuch as the two men were his guests, he must go inside and induce them to come out and surrender. The young man objected most vigorously.

“They are armed to the teeth,” he faltered; “and they’ll shoot me down.”

But he appreciated the fact that he was looking into the black mouth of Baker’s revolver, and hastily slid through the doorway. There was a sudden rustling of corn-blades, and the sound of voices in low conversation. All around the barn the soldiers were picketed, wrapped in inky blackness and uttering no sound.

In the midst of a little circle of candlelight Baker stood at the doorway with drawn revolver. Conger had gone to the rear of the barn. During the heat and excitement of the chase he had assumed command of the cavalrymen, somewhat to the umbrage of Lieutenant Doherty, who kept himself in the background during the remainder of the night. Further away, around the house, Garrett’s family huddled together trembling and frightened.

Suddenly from the barn a clear, high voice rang out, the voice of the tragedian in his last play.

“You have betrayed me, sir; leave this barn or I will shoot you.”

Baker now called to the men in the barn, ordering them to turn over their arms to young Garrett, and to surrender at once.

“If you don’t,” threatened Baker, “we shall burn the barn, and have a bonfire and a shooting match.”

At that Garrett came running to the door and begged to be let out. He said he would do anything he could, but he didn’t want to risk his life in the presence of two such desperate men. Baker therefore opened the door, and Garrett came out with a bound. He turned and pointed to the candle which Baker had been carrying since he left the house.

“Put that out or he will shoot you by its light,” he whispered in a frightened voice.

Baker placed the candle on the ground at a little distance from the door so that it would light all the space in front of the barn.

Then he called again to Booth to surrender. In a full, clear, ringing voice a voice that smacked of the stage— Booth replied:

“There is a man here who wishes very much to surrender,” and then they heard him say to Herold, “Leave me, will you? Go; I don’t want you to stay.”

At the door Herold was whimpering: “Let me out; I know nothing of this man in here.”

“Bring out your arms and you can come,” answered Baker. Herold denied having any arms, and Booth finally said: “He has no arms; the arms are mine, and I shall keep them.”

By this time Herold was praying piteously to be let out. He said he was afraid of being shot, and he begged to be allowed to surrender. Baker opened the door a little, and told him to put out his hands. The moment they appeared Baker seized them, whipped Herold out of the barn, and turned him over to the soldiers.

“You had better come, too,” Baker then said to Booth.

“Tell me who you are and what you want of me. It may be that I am being taken by my friends.”

“It makes no difference who we are,” was the reply. “We know you and we want you. We have fifty well-armed men stationed around this barn. You cannot escape, and we do not wish to kill you.”

There was a moment’s pause, and then Booth said falteringly:

“Captain, this is a hard case, I swear. I am lame. Give me a chance. Draw up your men twenty yards from here, and I will fight your whole command,”

“We are not here to fight,” said Baker; “we are here to take you.” Booth then asked for time to consider, and Baker told him that he could have two minutes, no more. Presently he said:

“Captain, I believe you to be a brave and honorable man. I have had half a dozen chances to shoot you. I have a bead drawn on you now—but I do not wish to kill you. Withdraw your men from the door, and I’ll go out. Give me this chance for my life. I will not be taken alive.”

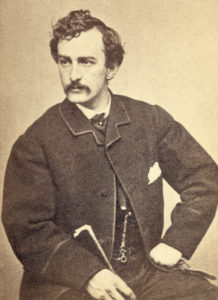

Even in his deep distress Booth had not forgotten to be theatrical. If he must die he wished to die at the climax of a highly dramatic situation.

“Your time is up,” said Baker firmly; “if you don’t come out we shall fire the barn.”

“Well, then, my brave boys,” came the answer in clear, ringing tones that could be heard by the women who cowered on Garrett’s porch, rods away, “you may prepare a stretcher for me.” Then, after a slight pause, he added, “One more stain on the glorious old banner.”

Conger now came around the corner of the barn and asked Baker if he was ready. Baker nodded, and Conger stepped noiselessly back, drew a handful of corn-blades through a crack in the barn, scratched a match, and in a moment the whole interior of the barn was brilliant with light. Baker opened the door and peered in.

Booth had been leaning against the mow, but he now sprang forward, half blinded by the sudden glare of fire, his crutches under his arms and his carbine leveled in the direction of the flames as if he would shoot the man who had set them going. But he could not see into the darkness outside. He hesitated, then reeled forward again.

An old table was near at hand. He caught hold of it as though to cast it top down on the fire, but he was not quick enough. Dropping one crutch, he hobbled toward the door. About the middle of the barn he stopped, drew himself up to his full height, and seemed to take in the entire situation.

His hat was gone, and his wavy, dark hair was tossed back from his high white forehead; his lips were firmly compressed, and, if he was pale, the ruddy glow of the firelight concealed that fact. In his full, dark eyes there was an expression of mingled hatred, terror, and the defiance of a tiger hunted to his lair. In one hand he held a carbine, in the other a revolver, and his belt contained another revolver and a bowie-knife.

He seemed prepared to fight to the end, no matter what numbers opposed him. By this time the flames in the dry corn-blades had mounted to the rafters of the dingy old building, arching the hunted assassin in a glow of fire more brilliant than the lighting of any theater in which he had ever played. And for once in his life, J. Wilkes Booth was a great actor. He was in the last scene of his last play. The curtain soon would drop.

Suddenly Booth threw aside his remaining crutch, dropped his carbine, raised his revolver, and made a spring for the door. It was his evident intention to shoot down any one who might bar his way, and make a dash for liberty, fighting as he ran.

There came a shock that sounded above the roar of the flames. Booth leaped in the air and pitched forward on his face. Baker was upon him in an instant, grasping both his arms to prevent the use of the revolver. But this precaution was entirely unnecessary. Booth would struggle no more. Another moment and Conger and the soldiers came rushing in. Baker turned the wounded man over and felt for his heart.

“He must have shot himself,” said Conger.

“No,” replied Baker; “I saw him every moment after the fire was lighted. The man who did do the shooting goes back to Washington in irons for disobedience of orders.”

In the excitement that followed the firing of the barn. Sergeant Boston Corbett, an eccentric character who had accompanied the cavalry detachment, had stolen up to the side of the barn, placed his revolver to the crack between two boards, and just as Booth was about to spring through the doorway, had fired the fatal shot. He afterward told Lieutenant Baker that he knew Booth’s movement meant death either for him (Baker) or for Booth.

Booth’s body was caught up and carried out of the barn and laid under an apple-tree not far away. Water was dashed in his face, and Baker tried to make him drink, but he seemed unable to swallow. Presently, however, he opened his eyes and seemed to understand the situation. His lips moved, and Baker bent down to hear what he might say.

“Tell mother—tell mother–” he faltered, and then became unconscious again. The flames of the burning barn now grew so intense that it was necessary to remove the dying man to the piazza of the house, where he was laid on a mattress provided by Mrs. Garrett. A cloth wet in brandy was applied to his lips, and under its influence he revived a little. Then he opened his eyes and said with deep bitterness:

“Oh, kill me, kill me quick.”

“No , Booth,” said Baker, “we don’t want you to die. You were shot against orders.” Then he was unconscious again for several minutes, and they thought he never would speak again. But his breast heaved, and he acted as if he wished to say something. Baker placed his ear at the dying man’s mouth, and Booth faltered:

“Tell mother I died for my country. I did what I thought was best.”

With a feeling of pity and tenderness, Baker lifted the limp hand, but it fell back again as if dead at his side. Booth seemed conscious of the movement; he turned his eyes and muttered hopelessly:

“Useless—useless”—and he was dead. When his collar was removed it was found that the bullet had struck the assassin under the ear, in almost the exact location that his own had struck the President. The great nerve of the spinal column had been severed, resulting in instant paralysis of the entire body below the wound.

About twenty minutes before Booth’s death, Conger had started for Washington, taking with him Booth’s arms, his diary, and other articles found on his person. While the Garretts were preparing breakfast for the hungry men, Booth’s body was wrapped in a saddle blanket and the blanket stoutly sewed together. The body was then placed in an ancient and decrepit market wagon owned by an old colored man, who had been forced into the service somewhat against his will.

Without waiting for breakfast, Baker, accompanied by a corporal, set out over the road for Belle Plaine, the negro driving the old horse as rapidly as he could. The cavalry guard was left to follow with Herold and the other prisoners. After crossing the Rappahannock at Rollins’s ferry, Baker traveled on for some distance, expecting every moment to see his guard come up.

Baker sent his orderly back to inform Doherty what road he had taken, and instructing him to come on at once. But no cavalry appeared. They met few teams, and the road grew wilder and more forbidding. Presently straggling bands of men in Confederate uniform appeared, riding dejectedly southward.

“What have you got there?” one of them called out; “a dead Yank?”

“Yes,” Baker replied, laughing.

This seemed to satisfy the questioner, and he passed on with a jest.

It had now grown hot and dusty, and Baker feared that Doherty’s men had been attacked and routed and that he might be overtaken at any moment, and Booth’s body recaptured. He was unnerved with loss of sleep and hunger, having been nearly three days in the saddle without rest. He was alone in an enemy’s country, he had lost his way, and the responsibility he had assumed weighed heavily upon him. The old horse was worn out with the rough journey, and it was difficult to get him up the sand-hills with his load. But Baker dared not stop for rest or food.

On one of the hardest hills the kingbolt of the rickety old wagon gave out with a snap; the front of the box dropped down, and Booth’s body lurched heavily forward. The big letters “U.S.” on the blanket were wet with the assassin’s blood, which had also trickled down over the axle and dribbled for miles along the road. The driver crawled under the wagon to repair the break, and some of the blood fell on his hand. He sprang back, shrinking in terror.

So horrified was he that he tried to leave his burden, wagon, horse, and all, and escape through the woods, but Baker forced him to continue on the journey. After thirty miles of heat and dust, up hill and down, they crept over the top of a sandy knoll, and Baker saw the blessed blue of the Potomac glimmering through the trees. It was just twilight, and the tinkle of cowbells came up drowsily from the riverbank. Booth’s body, wrapped in blue, was now gray with dust.

Reaching the water’s edge. Baker could find no trace of dock or steamer. Sometime during the war the government had changed the landing from its old location known to the negro, to a point nearly a mile further up the river. They could see the “John S. Ide” lying at the wharf, but they had no boat with which to reach it. To shout might bring the marauding enemy sooner than friends.

With the help of the driver, Baker bore the body down to the river and hid it under a clump of willows. Securing a promise from the old driver that he would remain and watch faithfully, Baker started back, a distance of over two miles by the road, never sparing his jaded horse until he reached the tug. Doherty’s command was already there. Baker asked the corporal whom he had sent back why he did not return to him, and he said that Doherty would not allow him to.

A small boat from the tug was lowered, and with two of the crew to row, Baker soon reached the upper landing. The negro was found still on watch, faithful to his trust. The body was placed in the boat, and, a few minutes later, it was hoisted to the deck of the “John S. Ide.” Baker saw it properly under guard, and then sank in a stupor of sleep on the deck.

On reaching Washington the body was removed to the gunboat “Saugatuck,” which lay at anchor in the navy yard, and there the autopsy and the inquest were held.

Conger had brought the news of the capture to Washington many hours before, and every town in the country was ringing with the tidings. The moment the evidences of Booth’s death—the diary, two revolvers, the carbine, the belt, and the compass—were placed in Colonel Baker’s hands, he carried them to the office of the Secretary of War.

“I rushed into the room,” relates Colonel Baker, “and said, ‘We have got Booth.’ Secretary Stanton was distinguished during the whole war for his coolness, but I never saw such an exhibition of it in my life as at that time. He put his hands over his eyes and lay for nearly a minute without saying a word. Then he got up, put on his coat, and inquired how the capture had come about.”

Immediately on his return Lieutenant Baker was called to the office of Secretary Stanton, where he related the story of the capture. Mr. Stanton had Booth’s carbine, and when the narrative was finished, he handed it to Baker with the question,

“Are you accustomed to using a carbine? If so, what is the matter with this one? It cannot be discharged.”

Baker examined the weapon, and found that a cartridge had slipped out of position so that when the lever was worked it could not be thrown under the hammer. Perhaps it was for this reason that Booth cast it aside in the barn. It was a part of the ill luck that followed the assassin and every one with whom he came in contact from the moment he fired the fatal shot at President Lincoln.

Late in the afternoon of the second day after Booth’s body was brought to Washington (April 28th) Colonel Baker received orders to dispose of the body in the way that seemed best to him, so that Booth’s Confederate friends might never get it.

Taking Lieutenant Baker with him, he started at once for the navy yard, stopping on the way at the old penitentiary prison. They reached the ironclad on which Booth’s body reposed just as twilight was deepening into night.

The body was sewn again in its bloody winding-sheet and lowered into a small rowboat. Hundreds of people stood watching on the shore, knowing that it was Booth’s body, and determined to ascertain what was to be done with it. Colonel Baker had brought with him a heavy ball and chain, which he placed in the boat by the side of the body, making no apparent attempt at secrecy.

He and Lieutenant Baker stepped into the little craft, and a few strokes of the oars sent it speeding out on the black Potomac in the gathering darkness. It had passed from lip to lip that the body of Booth was to be sunk in the river, and the crowds followed eagerly along the shore until the little rowboat and its occupants disappeared. It was a moonless, starless night, warm with mid-spring. In the distance blinked the lights of the city, vying with the near illumination of the river craft. For nearly two miles the boat drifted silently. Its occupants spoke no word; there was not even the creak of an oarlock.

At Geeseborough Point the river widens and its shallows grow rank with, rushes and marsh weeds. Here the boat was driven toward shore until its speed was quenched in the mud of a little cove. It was the loneliest of lonely spots on the Potomac—the burial ground of worn-out and condemned government horses and mules—a place dreaded alike by white men and negroes. For a time the two officers listened intently to make sure they were not followed. All was quiet on the Potomac. No sounds reached their ears but the strident croak of bullfrogs and the lapping of the water on the sedgy shore.

Presently the boat was turned and pulled slowly back toward the city. The utmost caution was observed to make no sound. They dreaded even the lisping of the oars and the faint lapping of the water at the gunwales. Suddenly against the sky loomed the huge black hulk of the old penitentiary. A few more strokes and the boat reached the base of the grim, forbidding wall. Silently they crept along until they came to a hole let into the solid masonry close to the water’s edge. An officer who stood just inside of the opening, challenged the party in a low voice, and Colonel Baker answered with the countersign.

They lifted the body from the boat and carried it through the hole in the masonry into a convict’s cell. A huge stone slab, worn with the fretting of many a prisoner, had been lifted up, and under it there was a shallow grave, dug only a few hours before. A dim lantern outlined the damp walls of the cell and emphasized the shadows.

Just at midnight Booth’s body was lowered into the black hole, the stone slab was replaced over the unhonored grave, and the two officers crept back to their boat and returned to Washington.

It was believed that the body had been sunk in the Potomac, and for days the river was dragged by Booth’s friends in the hope of finding it. The newspapers gave circumstantial accounts of the watery burial, and “Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly” for May 20, 1865, had a full-page illustration showing Colonel Baker and Lieutenant Baker in the act of slipping the body over the edge of the boat into the river. It was entitled “an authentic sketch.”

For several years no one but Colonel Baker, Lieutenant Baker, and two or three other officers knew of the disposition of Booth’s body. Indeed, there were rumors, widely credited in certain parts of the country, that Booth never had been captured. Later, however, after the heat and excitement of the time had subsided, permission was given for the removal of the remains to Baltimore, where they now rest.

Before the trial of the conspirators was begun, Lieutenant Baker was again sent into lower Maryland to collect evidence against Booth and his accomplices. He was so far successful as to find the boat in which Booth and Herold crossed the Potomac, and also Booth’s opera-glass, hidden near Garrett’s house, both of which he took with him to Washington.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

By subscribing, you will automatically receive the latest episodes downloaded to your computer or portable device. Select your preferred subscription method above.

To subscribe via a different application: Go to your favorite podcast application or news reader and enter this URL: https://clearwaterpress.com/byline/feed/podcast/