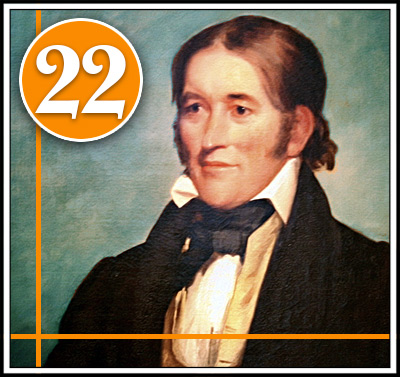

David Crockett

Episode 22•

David Crockett and the Most Desperate Defense in American History

• Nowhere but in America would such a career as Crockett’s have been possible.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Email | TuneIn | RSS

SHOW NOTES ____________

David Crockett

By Cyrus T. Brady

Part One

A Typical American

“MY DOG.”

THAT’s what David Crockett said he would never wear on his collar. And the declaration of individual right following may be taken as indicating what David Crockett really was. It reads: “I am at liberty to vote as my conscience and judgment dictate to be right, without the yoke of any party on me, or the driver at my heels with the whip in his hands, commanding me to ‘Gee-whoa-haw‘ just at his pleasure.”

In his autobiography, one of the most naive and delightful of books, he takes occasion to defend his bad spelling by remarking that he despised “the way of spelling contrary to nature!”

It may be said, in passing, that many of his most eminent fellow-citizens and contemporaries shared his contempt for the rules of orthography. In that book he speaks of himself with the utmost frankness; as for instance:

“Obscure as I am my name is making a considerable deal of fuss in the world. I can’t tell why it is, nor in what it is to end. Go where I will everybody seems anxious to get a peep at me; and it would be hard to tell which would have the advantage if I, and the ‘ Government,’ and ‘ Black Hawk,’ and a great eternal big caravan of wild varments, were all to be showed at the same time in four different parts of any of the big cities of the nation, I am not so sure that I shouldn’t get the most custom of any of the crew!”

A modest man was David, it would appear, and a confident author, too; witness this assertion:

“I don’t know of anything in my book to be criticised by honorable men. Is it my spelling? that’s not my trade. Is it my grammar? I hadn’t time to learn it and make no pretension to it. Is it in the order and arrangement of my book? I never wrote one before and never read very many; and of course know mighty little about that. Will it be on authorship? this I claim and I’ll hang on to it like a wax plaster!”

There never was the slightest room for misunderstanding where Crockett was concerned. His character was plainness and simplicity itself. He usually hit the mark at which he aimed, whether with a rifle or not, in life, so clearly and plainly that dispute was impossible. Even the “‘coon” up the tree upon which he “drew a bead” with his famous weapon, the death-dealing “Betsy,” at once recognized the futility of resistance, and, being temporarily endowed with speech, remarked, “Don’t shoot, Colonel, I’ll come down.” True, Crockett would not be Andrew Jackson’s dog, and because he countered some of the President’s plans he had to give way as did nearly everyone else in like circumstances. But nothing less than “Old Hickory” ever mastered or moved this redoubtable pioneer unless it was a woman. His was a susceptible heart!

Nowhere but in America would such a career as Crockett’s have been possible. With Jackson and Houston he represents a phase of American life, opportunity, and success, peculiar to the time and not to be repeated again. Though he was the least and humblest of the famous trio in both achievement and reputation, he was not unworthy of association with them. And upon the score of manly, lovable qualities he stood first of the three. His famous motto, which he earnestly strove to live up to, was of the very best:

“Be sure you’re right, then go ahead!”

Crockett was born at Limestone, Tennessee, on the seventeenth of August, 1786. His father was an Irish immigrant who had fought in the Revolution at King’s Mountain— a patent of nobility on the frontier. His mother was an American girl. His parents were poor but happy and therefore honest it may be inferred. Young David grew up in the wilds of Tennessee, a tall, sturdy, swarthy lad, with hair black and straight as an Indian’s and keen yet merry eyes to match. He took to the forest instinctively, loving it, mastering its hidden lore, knowing its secrets, and little else apparently.

At the age of twelve he was apprenticed to a Dutch teamster, very much against his desire. After an enforced journey of four hundred miles to Virginia he ran away, and not daring to follow the road for fear of pursuit, he plunged into the wilderness and made his way back home after a hazardous and wonderful journey alone through the trackless woods. He was thereafter sent to school, where he spent just four days. Having whipped a larger and older boy who attempted to tyrannize him, he played truant to avoid punishment, and when detected ran away again.

He spent some three years in teaming and nearly two years with a hatter, and then returned home. He found his people in straitened financial circumstances and generously worked a year to cancel two notes amounting to $86 which a neighbor held against the elder Crockett. Thereafter he resolved to go to school. Love sent him there. The young girls of the vicinity scorned him for his ignorance, which of books at any rate was dense, not to say, total. As he said long after :

“But it will be a source of astonishment to many who reflect that I am now a member of the American Congress—the most enlightened body of men in the world—that at so advanced an age as the age of fifteen I did not know the first letter in the book!”

He continued at school for six months, working two days a week for his board and attending the sessions on the other four. And that completed his education. At the age of fifteen he “struck out” for himself and became a farm laborer, teamster, trapper, hunter, and general frontiersman. After various love affairs more or less serious, in 1809 he married a young Irish girl, with whom he moved westward to Franklin County and began housekeeping with “fifteen dollars’ worth of things fixed up pretty grand ” For six years the young couple were very happy. They had plenty to eat, largely the result of Crockett’s skill with old “Betsy,” enough to wear, the fruit of the young wife’s loom, and they exemplified in their lives his saying, “For I reckon we love as hard in the backwoods as any people in the whole creation!”

The death of his first wife in 1815 was a sad blow to him and his young children. In 1813 Crockett served with credit as a scout under Jackson in the Creek War. In 1816 he married again, this time a widow. There were three sets of children who lived together in an amicable if happy-go-lucky way. In 1821 he was elected a magistrate and a colonel of militia, although at the time he says he had never read a newspaper! Such was his popularity that he was successively elected to the State Legislature and then to Congress, where he served two terms; his ignorance, his oddity, his humor, his bravery, and his shrewdness, making him a figure of national prominence. Failing of re-election because of his antagonism to the policy of his friend Jackson, and finding any future political career in Tennessee closed to him, he determined like many southern men of that day to go to Texas, then in the beginning of her efforts for freedom. There he hoped to make his fortune and there he found his end. And truly nothing in his life became him better than the ending of it!

Part Two

The Lone Star Republic

By the treaty of 1819 with Spain the United States relinquished all claim to the western part of Louisiana, so called, lying south of the Red River and west of the Sabine, including the territory now comprised within the present state of Texas, then a part of the vice-royalty of Mexico. In 1821 Mexico revolted from Spain, and became the Republic of Mexico. Texas became one of its states.

The first American colony of any moment had been planted there in 1820 under the leadership of Stephen T. Austin, justly styled “The Father of Texas.” Successive immigration from the southern United States during fifteen years had brought the number of white Americans within the quarter million miles of Texas land up to twenty thousand, with a small but steadily increasing number of negro slaves. The Spanish or Mexican population was inconsiderable.

The character of the American immigrants was not uniform. There were many insolvent debtors who had fled from their creditors in the States, broken shop-keepers leaving the letters ” G. T. T.” (Gone to Texas) chalked upon their doors, not a few adventurers and soldiers of fortune, and as everywhere, some scoundrels, but the general average of the American settlers was remarkably high. The majority were honest, capable, law-abiding, hard-working people of the middle class, the best stock out of which to build a nation. Accustomed to hunting and frontier life, they were bold and hardy, if reckless and impatient of discipline and restraint. All of them, like Crockett, were expert riflemen.

Meanwhile, the Mexican government became the prize of a succession of worthless adventurers, using their opportunities for their own aggrandizement. Finally, in 1833, one Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna seized the Presidential office, abolished the Congress and made himself Dictator. This petty ” Napoleon of the West,” as he loved to style himself, was as black-hearted a scoundrel as ever schemed himself into power. He was not without some of the qualities of a soldier, however, and he certainly knew how to win the confidence of his countrymen again and again, in spite of their frequent repudiations of him. His oppressive hand was at once laid upon Texas, and because the Americans would not tamely submit to be deprived of every political right, they revolted. As a matter of fact they were eager to do so.

Part Three

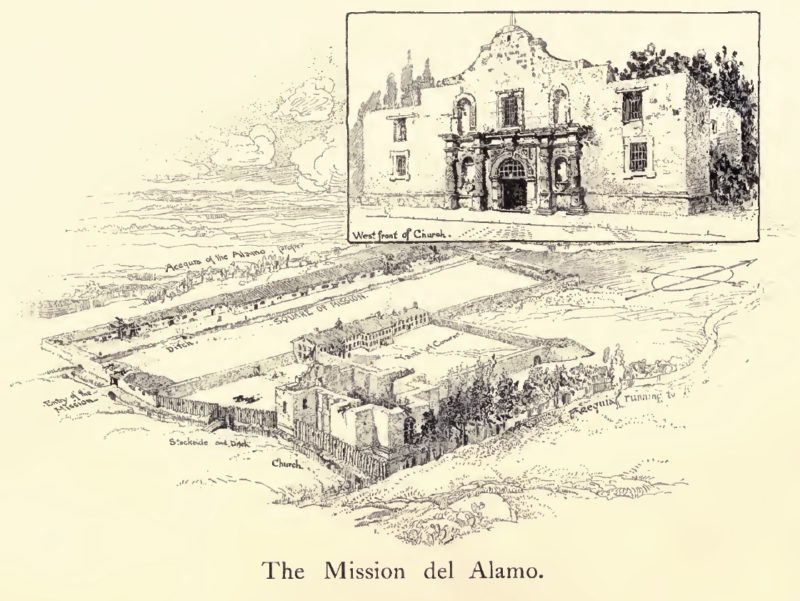

The Mission del Alamo

The Texan War of Independence began with a skirmish at Gonzales near the end of October, 1835. A Texan declaration of principles was adopted November I3th, 1835, and the Declaration of Independence on March 2nd of the following year. The battle of Concepcion was won by the Texans on October 28th, 1835, and on December l0th, after a siege and an assault which continued for six days, the city of San Antonio was captured, and every Mexican soldier was expelled from the territory. Hard by the town stood the buildings of the Mission of San Antonio de Valero, commonly called the Mission del Alamo, or the Alamo, a word signifying cotton-wood tree. The Alamo was founded by the Franciscans in 1703, and after various removals, established in its present location in 1722.

The mission buildings comprised a main plaza in the shape of a long parallelogram about fifty by a hundred and fifty yards; the enclosing wall, built of adobe bricks, was about eight feet high and three feet thick. On the west side of the plaza stood a row of one-story buildings, and along the middle of the east side for about sixty yards was a two-story convent eighteen feet wide. To the east of the convent lay a yard about a hundred feet square with walls over three feet thick and about sixteen feet high, further strengthened on the inside by an embankment. At the southeast corner of the yard stood the stone church of the mission, built in the form of a cross. A formidable stockade connected the church and the southeast corner of the main plaza. Fourteen small pieces of artillery were mounted on the walls, including three in the chancel of the church. Two aqueducts touching the west wall and the church respectively provided water.

Early in 1836 the commander of this fort, if such the mission may be called, was Lieutenant-Colonel William Barrett Travis, a young lawyer from North Carolina, a tall, manly, red-headed young fighter, then just twenty-eight years of age. Associated with him in the Alamo was Colonel James Bowie of Georgia—he of the sinister knife of the same name. Bowie was senior in age and rank to Travis, but had been disabled by a fall and was then confined to his room by the injury, and he was therefore compelled to yield the command to Travis. Bowie was not too ill to fight, though, as we shall see. Under these two officers were about one hundred and forty officers and men, a totally inadequate force, as it would have required at least a thousand to man the extensive lines of the Alamo.

To this little band early in February, 1836, came a welcome re-enforcement in the shape of David Crockett with twelve of his Tennessee friends and neighbors willing to help Texas to gain her independence—and, incidentally, to join in what they all dearly loved: any kind of a fight! They were all clad in hunting suits, with ‘coon-skin caps, and armed with long rifles and Bowie knives! It is significant of the spirit of the man, that Crockett refused to swear allegiance to “any future government of Texas,” until the word “republican” had been inserted after the word “future” in the prescribed form of the oath.

Part Four:

The Hundred and Eighty against the Five Thousand

On the twenty-third of February, 1836, Santa Anna in person appeared before the fort with the advance of his army and demanded its surrender. He had led some five thousand men of the Mexican regular army, with many camp followers and women, a forced march of one hundred and eighty leagues across a desert country in the depth of a Texas winter with its extremes of heat and cold and blasting storm. Only after incredible hardships and great losses had the terrible march been completed. That Santa Anna could do this is no small evidence of his capacity as a leader and his ability to inspire his men to heroic action.

His arrival was a complete surprise to the Texans; many of them were scattered through the town at a fandango at the time. When the alarm was given they repaired to the Alamo and Travis met the demand for a surrender by a shot from his battery, at the same time hoisting his flag. This was the white, red, and green banner of the Mexican Republic with two stars in the centre in place of the familiar eagle and serpent. The lone star flag had not then been adopted.

Santa Anna displayed a red ensign signifying that no quarter would be given, and began erecting batteries with which he opened fire. The Texans replied with good effect. The Mexicans, while greatly outnumbering the garrison, were not yet in sufficient force completely to surround the works, and the Texans might easily have escaped. Travis, however, had no. thought of retreating. He immediately despatched the following appeal for assistance:

To the people of Texas and all Americans in the World.

FELLOW CITIZENS AND COMPATRIOTS.I am besieged by a thousand or more of the Mexicans under Santa Anna. I have sustained a continual bombardment for twenty-four hours and have not lost a man. The enemy have demanded a surrender at discretion; otherwise the garrison is to be put to the sword if the place is taken. I have answered the summons with a cannon shot and our flag still waves proudly from the walls. I shall never surrender or retreat. Then, I call upon you, in the name of liberty, of patriotism, and of everything dear to the American character, to come to our aid with all dispatch. The enemy are receiving re-enforcements daily and will no doubt increase to three or four thousand in four or five days. Though this call may be neglected, I am determined to sustain myself as long as possible and die like a soldier who never forgets what is due to his own honor and that of his country.

Victory or Death!

W. BARRETT TRAVIS,

Lieutenant-Colonel, Commanding.P. S. The Lord is on our side. When the army appeared in sight we had not three bushels of corn. We have since found in deserted houses eighty or ninety bushels and got into the walls twenty or thirty beeves.

Brave Travis! Other ringing sentences from his subsequent letters are worth quoting:

“I shall continue to hold the lamo until I get relief from my countrymen, or I perish in its defence.”

“Take care of my little boy, if the country should be saved I may make him a splendid fortune, but if the country should be lost and I should perish, he would have nothing but the proud recollection that he is the son of a man who died for his country.”

The thought of that little boy adds a touch of pathos to the story of the dauntless cavalier and his devoted band facing fearful odds.

Travis also despatched messengers invoking assistance from adjacent garrisons. Colonel James Butler Bonham, a young South Carolina volunteer, broke through the Mexican lines and rode post-haste to Colonel Fannin at Goliad, some two hundred miles to the southeast. Fannin promptly started out with three hundred men and four guns, but his ammunition wagons broke down, his transportation failed him, his provisions gave out, he could not get his artillery over the rivers, and he was reluctantly forced to turn back.

He tried in vain to keep Bonham with him. “I will report to Travis or die in the attempt,” returned the chivalric Carolinian, who had been a schoolboy friend of Travis, as he started back to the fort. At one o’clock in the morning of March 3rd he succeeded in reaching the fort after a long and dangerous ride in which he literally took his life in his hands. So far as any one could see he came back to certain death with his friends. Travis had received a valuable re-enforcement of thirty-two heroic fellows from Gonzales, who dashed through the lines on horses, cutting their way into the Alamo at three in the morning. Captain J. W. Smith led them and they came cheerfully, although they knew what their fate would be if the place was stormed.

For eleven days the siege continued. The Mexicans lost heavily whenever they came within rifle range; on one occasion they tried to bridge the aqueduct and thirty of them were instantly killed. Sorties were made by the besieged at first, but were soon given over. The bombardment of the works was continuous, but, strange to say, no Texan was killed, although the whole garrison was completely worn out by the strain of ceaseless watching and continual fighting. There is no question but they could have cut their way out and escaped at almost any time, but no one dreamed of such a thing. They were there to stay until the end, whatever it might be.

Santa Anna would undoubtedly get the fort eventually; well, he might have it by paying the price; so they reasoned, but that price would be one, in the words of a later revolutionist, that would “stagger humanity.” Knowing Santa Anna, they could have no doubt of his intentions toward them, especially as he had made no secret of his purpose to put them all to death unless they surrendered at discretion. The calm courage with which they faced this appalling certainty is as noteworthy as the high heroism of their last defense.

The last of Santa Anna’s army arrived on the second of March; he allowed them three days for recuperation and on the fifth held a council of war to decide upon the course to be pursued. The council, like every other, was divided, with a preponderance of opinion in favor of waiting for siege guns to breach or batter down the walls. Santa Anna, however, determined upon an immediate assault, to be delivered at daybreak the next morning. Twenty-five hundred picked men in four columns, commanded respectively by General Cos, who violated his parole thereby, and Colonels Duque, Romero and Morales, were detailed to make the attack. They were provided with scaling ladders, axes, and crowbars, in addition to their weapons; and the cavalry of the army was disposed at strategic points to prevent escape should any of the hundred and eighty defenders succeed in breaking through the assaulting columns. Or, possibly, their function was to cut down any panic-stricken Mexican who might wish to withdraw from before the death-dealing Texas rifles!

Colonel Duque was to lead the main assault on the north side, while a simultaneous attack was to be made on the east and west sides and at the redoubt covering the sally-port from the convent yard. No attack appears to have been contemplated on the stockade on the south wall at first. Accounts of what happened differ widely; it is to be remembered that no American lived to tell the tale, and it is hard to get at the absolute truth from Mexican testimony, and the frightened recollection of two dazed women and two servants. Each narrator must build his own account by considering all the testimony and weighing the evidence. This that follows seems to me to be what happened.

About four o’clock on Sunday morning, March the sixth, the notes of a bugle calling the Mexican troops to arms rang over the quiet plain, across which the first gray light was already stealing. Bugles caught up the shrill refrain, lights appeared in the circling camps, the trampling feet of hurrying men, the commands of the officers, the rattling of arms, the neighing of the horses, all apprised the weary garrison that the moment they had expected was at hand. They were instantly assembled.

What happened as they fell in on the plaza before they went to their several stations? Tradition has it that Travis paraded them, briefly addressed them, pointed out their certain fate, as he had sworn never to surrender, and bade any who desired to do so to leave him freely and escape while there was yet time. Not a man availed himself of the permission. “We will stay and die with you,” they cried unanimously as they repaired to their stations on the outer wall.

Cool, calm, and resolute, they waited the breaking of the battle storm; undaunted by the prospect, unshaken by the fearful odds before them. America has produced no better soldiers! Even the dozen sick men in the long room of the hospital with Bowie were provided with arms, of which, fortunately, they had a good supply, and they, too, shared the same heroic resolution.

It was early morning when all the dispositions were made on both sides, and the day was breaking clear, cool and beautiful, a sweet day indeed in which to die for home and country and liberty. The quiet watchers on the walls presently detected movements in the dark rank of the besiegers. They were coming, then! Music, too, was there. All the bands of the Mexican army stationed with Santa Anna on the battery in front of the plaza were playing a ghastly air called ” “Cut throat” ! And the red flag speaking of no quarter pointed out a deadly purpose. Well, the Texans needed none of these things to nerve their arms. Rifles were lifted and sighted, the lock-strings of the carefully pointed cannon were tightened; they could not afford to throw away any shots, there was no hurry, no confusion.

The Mexicans were nearer now. The bugles rang charge, the close ordered ranks broke into a run. From the east, the west, the north, they came, cheering and yelling madly! A shot burst from the plaza, the crack of the rifles broke on the air, a fusillade ran along the walls on every side. The cannon roared out, hurling into the faces of the Mexicans bags filled with hideous missiles. The advancing lines hesitated, paused, halted, fled! The first assault was beaten off, the ground was covered with dead and wounded; comparative stillness supervened.

The east and west columns had been driven to the north. Colonel Duque, gallant soul, re-formed them on his own brigade; there was a small breach in the north wall; he hurled the mass at it, himself in the lead. The Americans ran to the point threatened; again the withering rifle fire. Duque fell, desperately wounded; mortal man could not face that deadly discharge; the soldiers gave way once more repulsed a second time; would they dare come on again?

Far off on the east side the roar of battle still surged around the redoubt covering the convent yard. How went the battle there, thought the triumphant defenders of the plaza as they gazed on their flying foemen? It was a critical moment for the Mexicans. Santa Anna recognized it, and galloped on the field leading a re-enforcement. He noted that the west wall had been denuded of most of its defenders, and with soldierly decision threw his fresh troops against it, leading them in person, some accounts say. The hundred and eighty could not be everywhere, the few at the point of impact died, and the Mexicans entered the plaza, at last.

At the same time the officers drove the men up to the third assault on the north wall. Under the eye of Santa Anna they advanced for a last desperate attempt. Honor to those Mexicans for their bravery too. In this attack a bullet pierced Travis’ brain and he fell dead on the trail of a cannon. Bonham was killed serving a gun, the north wall was taken, the redoubt to the east was gained, the stockade was attacked, other soldiers swarmed up to the south wall, broke through the gate and came in on every side. The Texans were surrounded by fire and steel. Some of them ran back while there was yet time and rallied in the convent where Bowie lay dead. Others followed Crockett, now in chief command, to the church to die with him there. The whole Mexican army was upon them now, the nine score against the five thousand at last.

The old convent was divided into little cell-like rooms, each with a door opening into the yard or plaza, but with no connection between the rooms. A few Texans held each chamber, and into each smoke-filled enclosure the infuriated troops poured their gun fire and then rushed the rooms, to writhe and struggle over the bloody pavements until all the defenders are killed. No quarter indeed!

What of the invalids in the hospital fighting from their beds? Forty Mexicans fell dead before the door of the long room before they thought to bring a cannon and blow the defenders into eternity. Bowie lay alone in his room waiting with grim resolution for what was coming, pain from injuries forgotten, fevered pulse beating higher; his bed covered with pistols, and, near his hand, his trusty knife. A brown fierce face peered in the door, another and another, the room filled with smoke; yells and curses and groans rose from the floor where a trail of stricken soldiers reached from the door to the bedside. And one bolder than his fellows lay on Bowie’s breast with that awful American knife buried deep in his heart and Bowie dead as he had lived, sword in hand!

The only fight left now was in the churchyard. A little handful, bloody, powder-stained, desperate, were backed up against the wall. It was hand-to-hand work now on both sides, no time to reload, bayonet thrust against rifle butt in berserker fury.

“Fire the magazine,” says Crockett to Major Evans, the only remaining officer. The man runs toward the church where the powder is stored and is stricken down on the threshold. The Mexicans rush upon Crockett and his remnant. The keen death-dealing “Betsy ” has spoken for the last time, the old frontiersman has clasped it by the barrel now. Swinging this iron war-club he stands at bay, disdaining surrender. The Mexicans are piled before him in heaps, but numbers tell; they swarm about him, they leap upon him like hounds upon a great stag, they pull him down, bury their bayonets in his great heart, spurn him, trample upon him, spit upon him so he makes a fine end!

It is over. Gunner Walker, the last man in arms, is shot and stabbed, tossed aloft on bayonets, in fact. The flag is down. No one is left to defend it longer. Five wounded, helpless prisoners are dragged before Santa Anna and at his command butchered where they lie, or stand, some of the Mexicans officers to their credit be it said vainly protesting. Six people who were in the fort at the beginning were left alive by the Mexicans, two women, two children, and two servants, one a negro slave, the other a Mexican.

One hour! One short hour filled with such sublime struggle as has not been witnessed often in the brief compass of sixty minutes. The sun is shining. The plaza is filled with light, the light of morning, the light of heroic death, of self-sacrifice absolute; and the day breaks, a day of eternal remembrance. Wherever men live to love the hero, these will not be forgotten. By the defence of that old deserted Spanish House of Prayer, it was consecrated anew to the service of God, through the sufferings of men. Their sacrifice had not been in vain, for the cry that swept Texas to freedom, that drove the Mexican beyond the Rio Grande was

Remember the Alamo!

One scene remains of the splendid story. By Santa Anna’s orders the dead Texans, to the number of one hundred and eighty-two, were gathered together and arranged in a huge pyramid, a layer of wood, a layer of dead, and so on, and the torch applied. A not unfitting end. As. the dead demigod of Homeric days was laid upon his funeral pyre, as the dead Viking of later time was burned with his ship, so these modern heroes. The wind scattered their ashes on the spot their defence had immortalized and made it forever hallowed ground.

The hundred and eighty had done well, each one had accounted for more than four of the enemy, for the Spanish casualties are estimated as between six hundred and a thousand. And most was in hand-to-hand fighting. The Texan-Americans had done their best and given their all.

On the monument erected at the state capitol at Austin, to commemorate their unparalleled achievement, is graven this significant line :

” THERMOPYLAE HAD ITS MESSENGER OF DEFEAT, THE ALAMO HAD NONE.”

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

By subscribing, you will automatically receive the latest episodes downloaded to your computer or portable device. Select your preferred subscription method above.

To subscribe via a different application: Go to your favorite podcast application or news reader and enter this URL: https://clearwaterpress.com/byline/feed/podcast/