Capturing a Confederate Mail

Episode 2 •

Capturing a Confederate Mail

• This is the true story of one of the daring expeditions that fell to the lot of the Federal Secret Service Bureau during the Civil War.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Email | TuneIn | RSS

SHOW NOTES

Capturing a Confederate Mail

By Ray Stannard Baker

McClure’s, August 1899

This is the true story of one of the daring expeditions that fell to the lot of the Federal Secret Service Bureau during the Civil War. The facts were obtained from my father, Major J. S. Baker, who was one of the three men detailed to capture the stage-coach. I have tried, as far as possible, to let him tell the story in his own words.

In the month of February, 1863, it came to the notice of the War Department that a secret Confederate stage service was in operation between Baltimore and Richmond; and at the time the route was first traced by the agents of the department, the managers of the enterprise were grown so bold that they had ceased to limit their business to passengers and mail, and the boot of every stage was piled with trunks and boxes filled with contraband goods. Any trader who was shrewd and daring enough to slip through the Union lines with quinine, morphine, percussion caps, or other light munitions of war, was sure of selling his stock to the Confederate government at an enormous advance.

Secretary Stanton turned the information of his scouts over to General L. C. Baker of the National Secret Service Bureau, with his instructions scrawled in blue across the face of the document: “See if you can get hold of some of this mail or break up the business.”

It might seem easy to have sent out a raiding party in Virginia to take the stages. But the Federal lines at that time reached only as far as Dranesville, and the country beyond was given over to the ravages of guerrilla bands, which made the protection of the stage routes an important part of their duties. And if armed force could not insure the safety of the mail-carriers, there were innumerable opportunities in the mountain ravines and among the friendly Virginia planters for effectual concealment. Indeed, it would have been quite as appropriate to stalk a red deer with a cavalry company as to send a regular military detachment to capture a smuggler in Virginia.

General Baker hit upon a plan that was as simple as it was audacious. He detailed three of his men—Sherman, Traill, and me—and instructed us to push out boldly beyond our lines and strike the stage route somewhere well up in the mountains near Leesburg. Leesburg was then the headquarters of a considerable body of Confederate cavalry and a base of military operations for northern Virginia. There being only three of us, the general thought we could creep up to the enemy’s lines, or even beyond them, without attracting any attention. We might then wait at some obscure station on the mail route, and at the appearance of the stage, quietly capture it, search the passengers, destroy any contraband goods that might be in the stage boot, and ride back to Washington with the Confederate mails stowed safely away in our saddle-bags. The very boldness and swiftness of the movement would warrant its success. The general told us not to try to bring- in any prisoners, but impressed upon us the necessity of getting the mails.

Traill was a Virginian born, and Sherman was a plucky Yankee who had gone to Virginia some time before the war as overseer for General Roger Jones of Fairfax County. Their acquaintance with eastern Virginia and its people admirably fitted them for such an expedition. I was thrown in to make measure, and it was my cue to keep well in the background until I was needed. Traill’s soft Southern drawl would clear the way for all of us.

We left Washington on the evening of February 9, 1863. We were clad in citizen’s clothes of nondescript gray, and each of us had a heavy ammunition belt buckled well up under his coat. Sherman and I each took a Colt’s revolver, and Traill, who was always fearful of being underarmed, took two. There was nothing to distinguish us from ordinary citizens traveling in the common highway, with the exception of our secret service badges, which gave us almost unlimited privileges in passing through our lines and in getting such assistance as we might need from the soldiery.

We rode silently, in single file, and passed well to the south of Leesburg before climbing the foothills of the Blue Ridge.

Morning found us in a little settlement at the forking of the road. It was a mere three-corners, with a post-office, a blacksmith shop, and two or three dilapidated houses. It was called Laskey’s, as I remember it, after the man who kept the post-office.

Laskey’s place was a little one-story, unpainted building, with a sagging porch jutting out over the road. It was set fairly on the mountain slope, and the land behind it dropped away abruptly into a deep ravine, with densely wooded sides. Laskey kept the post-office in a box-like front room, and he and his family lived in the rear.

We tied our horses at a hitching-bar near the store, where we could reach them easily in case of need. Traill walked into the building, and inquired when the stage would be along. Laskey was quite taken off his guard. “Directly, I reckon,”he said. Traill sat down on a nail-keg and lighted his pipe, and we fell to talking.

For a time Laskey was restless and evidently suspicious, but Traill’s drawl and Sherman’s evident familiarity with the Loudoun County names thawed him out, and he was soon talking freely. He thought we would be perfectly safe in mailing our letters to Richmond, and he explained much at length how careful the driver was to store the mail in a hidden box under the seat. He also had a good deal to say about the valor of the blockade-runners, and how well they were armed.

About the middle of the forenoon Laskey reckoned that he heard the stage coming. Traill knocked the ashes out of his pipe, and I hitched my elbows to feel the friendly crook of my revolver butt beneath my coat. We followed Laskey out into his little porch. The stage was already half-way down the sandy hill, the horses bowling along at a rocking gallop, with the driver perched stiffly up behind. Traill pushed the lank postmaster well to the front, and kept him much in friendly evidence.

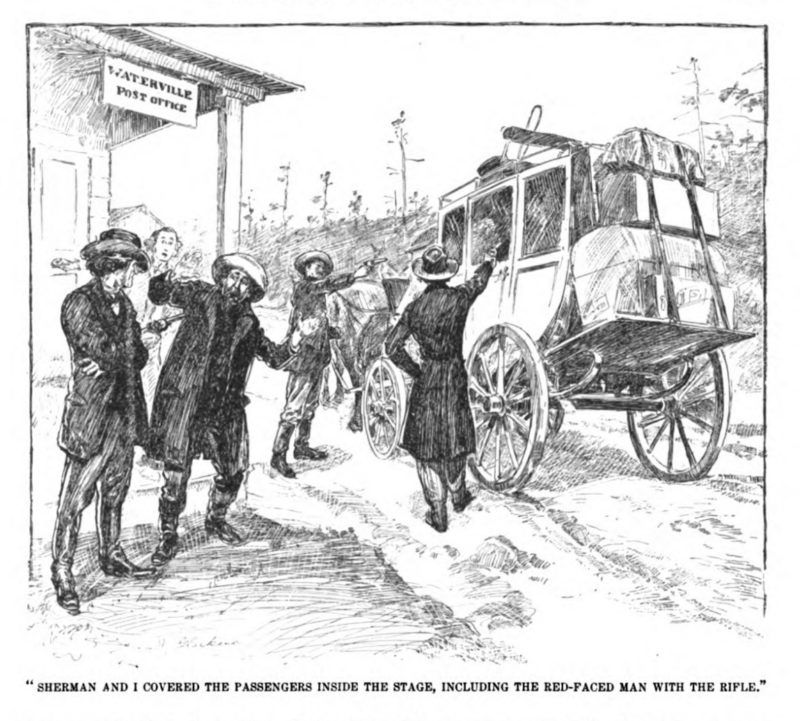

When the stage stopped, the driver came down from wheel to hub and stretched his legs. Several travel-worn passengers, one a woman, looked out suspiciously from the interior of the stage. One powerful, red-faced man carried a handsome rifle, and seemed uncertain just what to do with it. The boot behind was piled high with baggage. “Any mail?” asked the driver.

Traill stepped up. “We would like to have you stay here for a few minutes,” he said; “we are going to examine your baggage.”

The driver’s jaw dropped. “Who are you?” he demanded angrily, reaching into the pocket of his overcoat. Traill’s revolver flashed up and clicked, and I remember with what ludicrous alacrity the driver’s hands went up. Sherman and I covered the passengers inside of the stage, including the red-faced man with the rifle, who was in a chill of fright.

“You are prisoners,” Sherman said to them, “and if you keep quiet, there will not be any shooting.”

We drove them like a flock of sheep into the post office, and I stood at the doorway and kept guard. Traill sprung up the side of the stage, tore away the coverings of the driver’s seat, and threw down three pouches of mail about the size of fat saddle-bags. Sherman cut the straps that supported the boot, and sent the trunks and boxes tumbling into the sand. Then he found an ax near Laskey’s chopping-log, and cracked off the tops of them one by one. Having laid bare the baggage, Sherman and Traill both began to throw it out.

The upper part of most of the trunks was filled with clothing. Below this there was a varied assortment of contraband goods. They took out package after package of medicine—morphine and quinine principally—and burst them open in the sand. The bottles they cracked on the edges of the trunks. They also found several boxes of percussion caps, and a quantity of fine silk for hospital use.

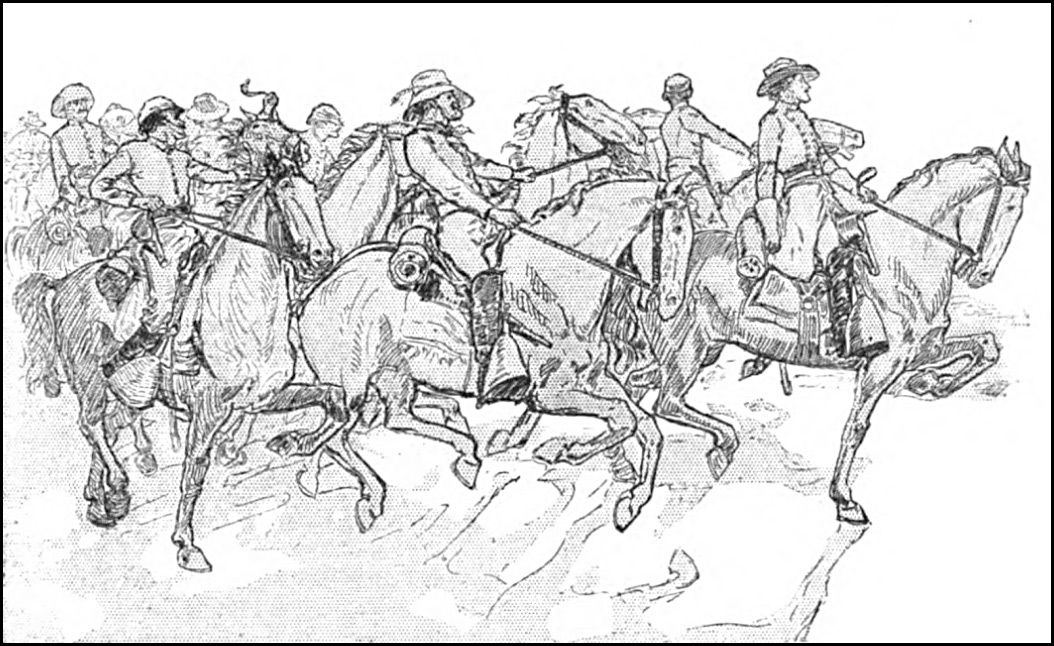

We were all watching the swift destruction of the goods, and Traill had his head deep in one of the trunks, when of a sudden there came the biting “pit, pit” of revolvers. A bullet drove into the door at my side, and sent the splinters stinging into my face. A company of cavalry had shot from among the pines up the hill, and was now racing straight down upon us, firing furiously. I remember how the revolvers blazed when the riders rose in their saddles to take aim.

Sherman and Traill pitched through the door, carrying me with them. Inside of the little store the stage passengers were scrambling under the counters and behind boxes, to protect themselves from the bullets. The woman was wailing her terror. For a moment we paused undecided; capture seemed imminent, and we knew that our Secret Service badges, if found upon us, were as good as a sentence of death. Just then we caught a glimpse of the stage driver. He was edging toward the door, evidently intending to escape.

“Get out of here,” Sherman shouted, “and take your passengers with you! Get out!” At the appearance of the driver waving his arms the firing ceased abruptly. The passengers ran after him, wild with terror, and tumbled into the stage. Just once the driver looked behind into Sherman’s revolver muzzle, and then he put the gad to his horses, and the crazy old stage went rattling down the hill, swaying from side to side like a ship on a choppy sea. All this had happened within the space of a long breath. The cavalrymen, evidently much astonished by our amazing maneuvers, had slowed up, and were advancing more cautiously.

“What shall we do?” I asked.

“Barricade the door,” said Traill.

“No; wait a minute,” answered Sherman. He stepped boldly across the porch, with his revolver in his hand, and seized the three mail bags, which had been left quite forgotten where Traill had dropped them. Then he turned and darted back, but before he could reach the doorway the cavalrymen opened fire. The bullets threw up little wisps of sand around him, and cut a groove along the porch; but Sherman came in without a scratch. “We’ve got what we came for,” he said.

By this time the cavalrymen were at the door. Sherman had just time to whirl around and raise his revolver. One of the Confederates who was well in advance threw himself from his horse, and shouted: “Here, you surrender!”

Sherman fired. We saw the cavalryman give in at the knees and go down in a heap. His horse plunged and reared at the end of the bridle rein. The poor fellow clung desperately, and finally managed to drag himself up and mount. His horse turned and galloped madly up the hill, the rider swaying dizzily and clinging to the pommel like a drunken man.

An instant later the whole troop was well out of pistol range. Traill and I kept blazing away at them until our revolvers were empty. “Well,” observed Traill, “we’re all here.”

“And we’re likely to stay,” said Sherman, pointing down the road. At the very first volley our horses had pulled loose from the rotten old tie-rail. They ran some distance down the hill after the stage, and we now saw two of the cavalrymen gathering them in, with our blankets, ponchos, and rations.

We were caught like rats in a trap. We might be attacked again at any moment, and we made ready to receive the enemy by piling barrels and boxes against the windows of our citadel, and barricading the front and rear doors, so that they would open only wide enough to admit of the passage of a pistol arm. Then we unslung our ammunition belts, and laid them out where they could easily be reached.

I remember with what unction Traill blew down the barrels of his revolvers, and with what nicety he fitted on the caps. All this time Laskey had been hovering around us with tears of abject misery and terror streaming down his sallow face. He assured us that we should all be killed and the store burned over our heads. “You take your wife and children, and go down cellar, and stay there,”said Traill. But the poor fellow was so terrified that we had to use the indisputable revolver argument before he would stir.

In the meantime the cavalrymen on the hill had not been idle. Several of them stripped down to charging trim, and presently we saw a big sergeant give his horse the spur and come down the road at top speed. Another rider followed at a distance of ten yards, and then another and another. Sherman and I sprang to the door, and Traill to the window. As the riders reached the store, they lay over on the off sides of their saddles and blazed at us from under their horses’ necks. We were awkwardly placed, but we returned their fire with spirit—“Gave ’em as good as they sent,” Traill said.

In his anxiety to get a better aim Sherman kept reaching further out of the door. “Take care, Sherman,” I called to him. “They can’t hit anything,” he responded, firing again. But the words were hardly out of his mouth when his revolver fell with a clatter and his hand dropped limp. From a ragged hole in his wrist the blood was spurting. “Sherman, you’re hit,” I said. “Never mind,”he answered; “I can shoot just as well with my left hand.” He stooped, seized his revolver, and fired the remaining charges before turning. I hastily bound up his wrist with a handkerchief, and he went at it again as if nothing had happened.

Quite suddenly we heard a commotion somewhere behind the building. Our barricade of boxes fell with a crash, and the back door was driven into splinters. Traill and I rushed into the little rear room. We understood in a flash the meaning of the cavalry show in front of the store—it covered a flank movement. At that moment we saw a big, square-jawed cavalryman drive against the broken door with his shoulder. It went down like paper, and he stood facing us in the ruins of our barricade, with a dozen men in gray scrambling after him.

At sight of us he threw up his revolver and fired. I felt the hot breath of the powder in my face, and the flash blinded me. An instant later Traill and I fired together. The cavalryman’s head dropped back, his mouth gaped open, and he rolled over and over down the steps. Then we continued firing until there wasn’t a patch of gray in sight. In the meantime the battle in front was growing fierce. I heard Sherman shouting, and turned to see him wave his empty revolver. I knew that he could not load, and I ran to help him. The barricade and the powder smoke so darkened the room that in my excitement I overturned the caps.

While I was scrambling on the floor to gather them up, there came a rush of feet across the porch outside, and the flimsy door was burst open. For a moment two of the cavalrymen struggled with our barricade, while several others fired from behind them into the room. Sherman seized a heavy stone molasses-jug from a shelf, and hurled it full at the stormers. It made a great noise, but instead of repulsing the attack, only encouraged it. They thought we were now out of ammunition, and they came at us again both in front and in the rear. But an instant later our revolvers were loaded again. Traill fired three times in quick succession, and then ran to the back door. Sherman and I remained in front, and it was the work of only a minute to send the cavalrymen flying.

For a long time after that everything was still. The smoke, that had done so much in protecting us from the bullets of the stormers, cleared away, and we reloaded our hot revolvers and rebuilt our barricades. We also took the precaution of hiding our Secret Service badges in the lining of our coats. We dared not throw them away for fear we could not get back to Washington in case we escaped, and yet we dreaded being captured with them in our possession. Traill returned to the solace of his pipe, and we discussed the situation with some misgivings.

Presently we heard a commotion in the cellar below us. Laskey’s wife and children began to scream, and a moment later the postmaster himself thrust an ashy face above the trap-door. “They’re settin’ the store on fire,”he said. We listened intently. Behind the building some one was moving stealthily. “They’ll burn us all up,”groaned Laskey; “they’re carryin’ straw for kindlin’.”

Some one shouted to us from the hill outside, and we saw a single cavalryman, a lieutenant, riding down toward the store. He held his saber aloft, and a white handkerchief fluttered at its point. Sherman answered from the window. “What do you want?”

“Come out of there and surrender.”

“You’ve called at the wrong place,” answered-Sherman.

“If you don’t, we’ll fire the store. I came down to give you fair warning. We’ve got the place surrounded, and you can’t escape.”

We made no answer, and the lieutenant shouted again: “Are you going to surrender?” “No,” answered Sherman.

The lieutenant wheeled, and galloped back up the hill, and we again heard the noises back of the building.

“They’re goin’ to burn us out, sartin sure,” wailed Laskey.

“No, they won’t,” said Traill; “you go out and tell ’em this is your property, and they must stand responsible if they burn it.”

“All right,” he answered eagerly. “Come up, Julia.”

“No,” interrupted Traill, “you must go alone.”

“But my wife will be burned.”

“You tell ’em they mustn’t burn this store,” ordered Traill, fairly pushing him from the door. He went out, waving his arms and shouting that he was innocent. We could hear the low grumble of his talk with the men at the corner, and then everything was still. After a seemingly endless wait we saw him running down the road, followed by the lieutenant and several privates. A hundred yards from the store they stopped. Sherman stepped out on the porch with his revolver in his hand.

“You fellows better surrender,” shouted the lieutenant; “we don’t want to burn you out. This man’s family is in the store, and we have no desire to injure any of them. You’ve got three men, and we’ve got two hundred and fifty. We’re going to take you sooner or later, and the sooner you come out the better it will be for you.”

Sherman stepped back into the store. “I don’t propose to surrender,” he said; “what do you say?”

“I don’t,” I said.

“Nor I,” answered Traill.

“We won’t surrender,” reported Sherman from the porch.

“Then burn!” roared the lieutenant. He dug his spurs into his horse, and rode back well out of pistol range. Then he turned and waved his saber, evidently signaling to the men back of the house. A moment later we heard the crackling of the fire, and the smoke swept by the window.

Laskey, wild with terror, rushed down the hill, but Sherman refused to let him in. I ran to the trap-door, and tried to calm his half frantic wife and children. The smoke continued to grow more dense, and Traill pulled down part of the barricade, so that we could make a dash for our lives the moment it became necessary. But for some reason we saw no flames. If properly set, the fire should have enveloped the dry, flimsy building in thirty seconds. Gradually the smoke disappeared, and Traill observed that we had escaped a fiery death. When we did not offer ourselves up on the altar of our fears, white-winged peace in the guise of a handkerchief again hovered on the hill. “We can’t stay here all night for three Yanks, and we’ve decided that if you’ll sign a parole and give up your arms we’ll let you go free.”

We haggled for some time over the proposition. Traill and I saw in it the only possible loophole of escape, but Sherman opposed it. “I know those fellows better than you do,” he said; “they won’t think of recognizing a parole. The moment they got our arms they’d capture us.”And he made a disagreeable motion of his fingers across his throat. “They’re guerrillas, and responsible to nobody.”

Our ammunition was running low, night was coming on, and we had neither eaten nor slept for nearly twenty-four hours. Besides that, Traill and I could see that Sherman was suffering from the shot in his arm. although he never mentioned it. We argued the question for some little time, and Sherman finally yielded. Then there was more haggling as to the terms of the parole. Sherman insisted with all of the dignity of a major-general that we be allowed to carry away our side-arms, but the lieutenant argued, with some reason, that we had been fighting with our side-arms and that we should give them up. He evidently knew that the rebel mail was in our possession, for he expressly stipulated that we were to carry nothing away with us.

“If I go, the mail goes with me, parole or no parole,” said Sherman, in parenthesis to us. “We’ve got to have something to show for the trip.”

Everything being finally arranged, the lieutenant came down to the store with his orderly. Sherman gravely returned his salute. Laskey brought a pen and ink, and the lieutenant, whose name was Osborne, stooped and wrote the paroles on slips of paper, using the battered and bullet-scarred window sill for a writing-desk. He was a big, bluff, handsome fellow, and he treated us with great civility. Knowing that ordinary prisoners of war would receive much better treatment than scouts or Secret Service men, we posed as regularly enlisted soldiers, and gave our companies and regiments. We each signed one of the slips, and then Sherman knocked the caps from three of the revolvers. and handed them over one by one. It was like parting from our dearest friends.

The lieutenant took them gravely, and gave them to his orderly. “You used them well,” he said gallantly.

“We needed to,” responded Sherman.

Having received our ammunition, the lieutenant eyed us sharply.

“Nothing but pocket-knives,” put in Traill.

“You will now return to the top of the hill,” said Sherman, “and remain there until we can march away.”

“You are not to return to the store nor take anything with you,” said the lieutenant.

“We understand the agreement clearly.”

The lieutenant turned and mounted. Then he paused: “Our men are at the top of the hill,” he said, “and I warn you for your own good that they will not stand any trifling.”

“I would remind you that we are paroled prisoners of war,” returned Sherman with dignity. We stood as stiff as drum-majors, maintaining a ludicrous dignity, with our hearts in our boots, and the cavalrymen rode slowly away up the hill. The sun was just setting over the mountain tops, and the woods were quiet and hazy with the smoke of our little battle.

Before the lieutenant had gone halfway up the hill his command began to swarm out of the woods and ride down to meet him. This was distinctly contrary to our parole agreement, but the lieutenant seemed to encourage it.

“We’re in for it,” said Traill.

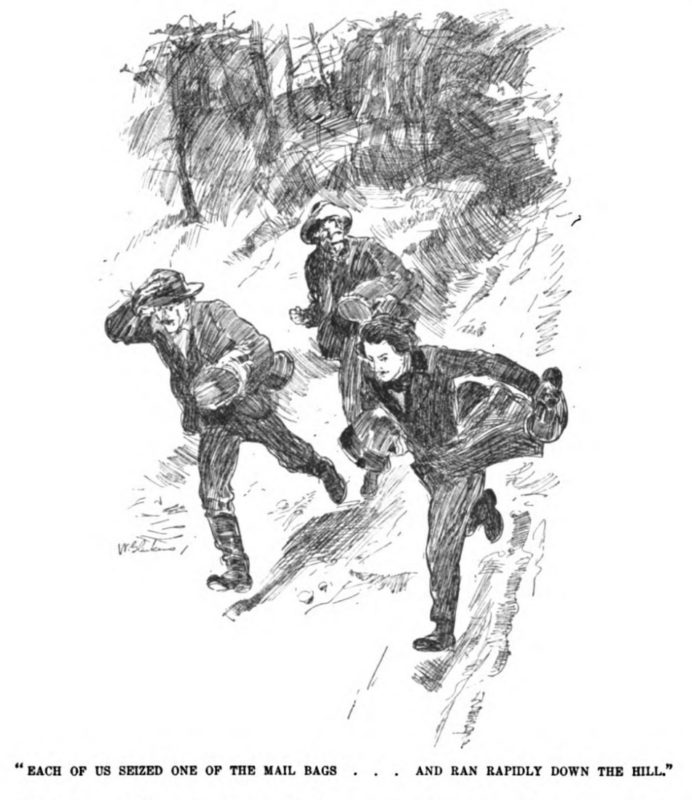

“No, we aren’t,” answered Sherman between his teeth. He turned instantly, and we followed him into the store. Each of us seized one of the mail bags, tore aside the barricade, sprung through the back door, and ran rapidly down the hill by a narrow, well-worn pathway.

Before we had gone fifty paces we heard the shouts of the cavalrymen in pursuit. At the bottom of the ravine a barrel was sunk deep in the oozy ground, and it was full of clear water that bubbled up out of the earth. As if with a common impulse, we dropped down and thrust our faces into it, and drank until we could hold no more. Bullets were better than the thirst from which we had been suffering all day long.

Again on our feet, we ran up the ravine, the bottom of which was a dry runway covered with boulders and sand. It cut the mountain slope from near the summit to the valley below, and its banks were half hidden with overhanging bushes, junipers, spruces, and scrub-pines, often growing so thick that it was impossible to force a passage. We ran desperately for five or ten minutes, and then we began to hear the clattering of feet in the runway below us.

Traill stopped, and reaching down, drew the fourth revolver from the depths of his cavalry boot. “They think we aren’t armed,” he said.

But Sherman and I were wholly defenseless, and we quickly concluded that concealment was our only course. So we scrambled up the side of the bank to the wooded slope of the mountain. Here we separated, Sherman and Traill penetrating further into the woods, while I wormed my way into a dense mat of junipers. It was agreed that if one of us was captured, he should not reveal the hiding-places of the others.

There we lay, hugging the moist ground, each with a bag of Confederate mail for a pillow. In the desire to have some weapon of defense at hand, I drew my clasp-knife and thrust it into the earth at my side. Then I covered my body as well as I could with dead leaves and juniper branches. Never before nor since have I longed so much for a revolver.

We heard the cavalrymen beating about in the bushes below us, evidently thinking we had gone down the ravine instead of up. But presently a considerable party of them approached and halted almost opposite my hiding-place. I lay so near the edge of the ravine that I could hear everything they said.

“We’ve lost their tracks,” said one; “and I reckon they’ve taken to the woods somewhere in here.”

A moment later they came scrambling up the bank, and I heard the officer direct them to march in open order, three or four yards apart. “They’re skulking somewhere in these junipers,” he said, “and if they don’t surrender, shoot ’em.”

Up to this point I had not felt the least anxiety for my safety. There was something inspiriting in the action and excitement of the skirmish at the store and the subsequent flight; but this lying defenseless and waiting to be flushed like a partridge from its cover told on my nerves. I found it difficult to resist the temptation to leap up and run, regardless of the consequences. I had not the slightest doubt that we should all be shot where we lay, for the cavalrymen were in no good humor. Nearer and nearer they came, tramping through the bushes. I sank down to my smallest, and grasped my clasp knife until my fingers ached. I had decided that if I was found, there would be at least one less Confederate cavalryman.

“See anything?” shouted someone back in the woods.

“No,” answered a voice almost over me.

At that one of the searchers thrust his saber viciously into a thicket not a dozen feet away from me. Then he paused, and looked around him in the gathering gloom. I was certain that he saw me, and as he took a step in my direction, I drew up one leg and prepared to spring at his throat. The leaves rustled, and he turned his head sharply, and poised his saber, again looking straight at me. My heart thumped so that I was sure he heard it; but he turned and poked into a thicket on the other side, and passed on up the hill, leaving me lying there panting and weak. Then I began to fear for Sherman and Traill, especially for Traill, for I knew that he would be sorely tempted to fire and take his chances. He always hated hiding. But the sounds of the search grew fainter and fainter, and presently I again heard the cavalrymen scrambling among the boulders in the bottom of the ravine.

“They can’t be anywhere on this side,” said one of them, and directly they crawled up the opposite bank, where they continued their search.

It was now dark in the woods, and presently from somewhere up the mountain we heard a bugle sounding, the cavalry recall. Ten minutes later it was followed by the lively music of the assembly. Then I heard the faint whistle of a cuckoo. It came again, twice repeated, and then I answered it. Five minutes later the three of us were gathered at the edge of the ravine, chilled and stiff and hungry, but safe.

All that night we skulked through the woods, choosing the most inaccessible bypaths and making wide detours around all of the plantations and settlements.

At noon we were marched to Federal headquarters at Dranesville in charge of a corporal of the guard, and before night we reported to General Baker in Washington. When the mails were opened they were found to contain much information of value, and we felt repaid in some degree for the loss of our horses and equipment.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

By subscribing, you will automatically receive the latest episodes downloaded to your computer or portable device. Select your preferred subscription method above.

To subscribe via a different application: Go to your favorite podcast application or news reader and enter this URL: https://clearwaterpress.com/byline/feed/podcast/