The Overworked President

The Overworked President

• According to White House rules, the President must open his house “daily, Sundays excepted, for the inspection of visitors.” No other citizen’s home has to be open for inspection.

The Overworked President

By Lincoln Steffens

McClure’s, April, 1902

There is in America a concern much greater than the United States Steel Corporation or any other commercial company, railway, industrial, or financial. It has the equivalent of a capital, not of a hundred millions, but of a hundred billions; an income of a hundred millions, and an annual expenditure sometimes as great as the income, sometimes greater. The stockholders number 76,000,000, and the conduct of the business affects their welfare more directly, immediately, and seriously than the management of any other company does its small partners, for the affairs of this concern are extraordinarily various and general. The greatest business organization on this side of the Atlantic Ocean, it is the foundation of all other enterprise.

Now the president of this concern has powers commensurate with the magnitude of its interests. So, too, his responsibility is great, his duties manifold, and his labor onerous. He has directors to advise, and executive officers to do for him; the organization is complete, well-tried, and sound, but all this machinery is subsidiary. The president himself is held accountable by the stockholders for everything. If he had none but the most important functions to fulfill, his time would be crowded.

Besides these essential duties, however, the president of this organization is expected, and does try, to perform a great many services that are utterly trivial. He is called upon to settle not alone the rows among his important agents, but also the petty squabbles of employees no better than gang foremen and section bosses; he himself appoints all sorts of menials, investigating and choosing between the claims of applicants for places relatively about as important as those of janitors and mule-drivers. He receives and distributes much of the mail of his subordinates, handling some of it with his own hands, and acting upon no little of it. Moreover, this man thus burdened is required by custom to keep open house for all comers. He has to allow his idlest stockholders to enter his own residence, walk curiously about his parlor; and those who are not satisfied may go into the room where he is talking to his business advisers, speak to him, shake him by the hand, while he is bound to listen to their troubles and congratulations and express sympathy or pleasure with them.

Absurd, is it not? No president of a purely business concern would or could do it. It could be true only of a government, of a democratic state, of the United States of America. Well, the point is that it is both true and absurd.

The president of the United States is the most powerful constitutional ruler on earth, and the most responsible. He is king and prime minister; as commander-in-chief of the army and navy, he really commands—directing and approving operations in the field during a war, and signing all commissions in time of peace—he is the head of all the departments, the adviser of the legislature, the responsible chief of the treasury, the controller of our international relations, and the active director of public improvements.

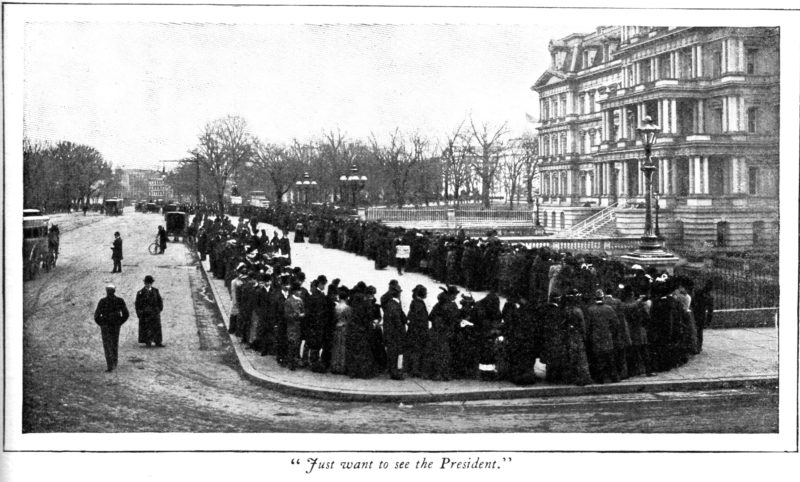

But the president is the head of the people also, and it is in this role and in that of party leader that we find him doing as outlined above. It is as the first citizen of the republic that he has to throw open part of his house “daily, Sundays excepted, for the inspection of visitors between the hours of 10 A.M. and 2 P.M.,” as the White House rules put it. No other citizen’s home has to be open for inspection; no other government office is subjected to this visitation. Here are the other White House rules:

“The Cabinet will meet on Tuesdays and Fridays from 11 A.M. until 1 P.M.”

“Senators and Representatives will be received from 10 A.M. to 12 M., excepting on Cabinet days.”

“Visitors having business with the president will be admitted from 12 to 1 o’clock daily, excepting Cabinet days, so far as public business will permit.”

By this arrangement the president should have for public business two whole days, Tuesdays and Fridays, when the Cabinet meets; all but three hours of every other day; and of these three, two hours for senators and representatives, who are supposed to call on matters of state. As a matter of fact, those rules are broken all to pieces. Visitors call on all days; they arrive before 10 o’clock, and the senators and representatives who call commonly bring with them constituents, so that the congressmen’s two hours are spoiled for them and for business by being made a time for public reception. The hour for citizens from 12 to 1 is no different from the two earlier hours, and there is usually such a crowd that the president is kept busy handshaking till 1.30 o’clock. Then he is likely to have at luncheon visitors whom he really wishes to see, but who could not reach him at the proper time. After luncheon, there are a few men with special appointments, and it is not till 3.30 o’clock or 4 that President Roosevelt, by an innovation which other presidents have tried and failed to introduce, gets away for a walk or a horseback ride. The evening is for public functions, or if they are private, the president has guests, often statesmen or politicians, almost always men of affairs, who keep the talk on “shop.” They stay after dinner, and others come in during the evening. This is, of course, all further testimony to the great power of the president; indeed, the position is magnificent. But it is ridiculous also, as anyone must see who spends a day with him.

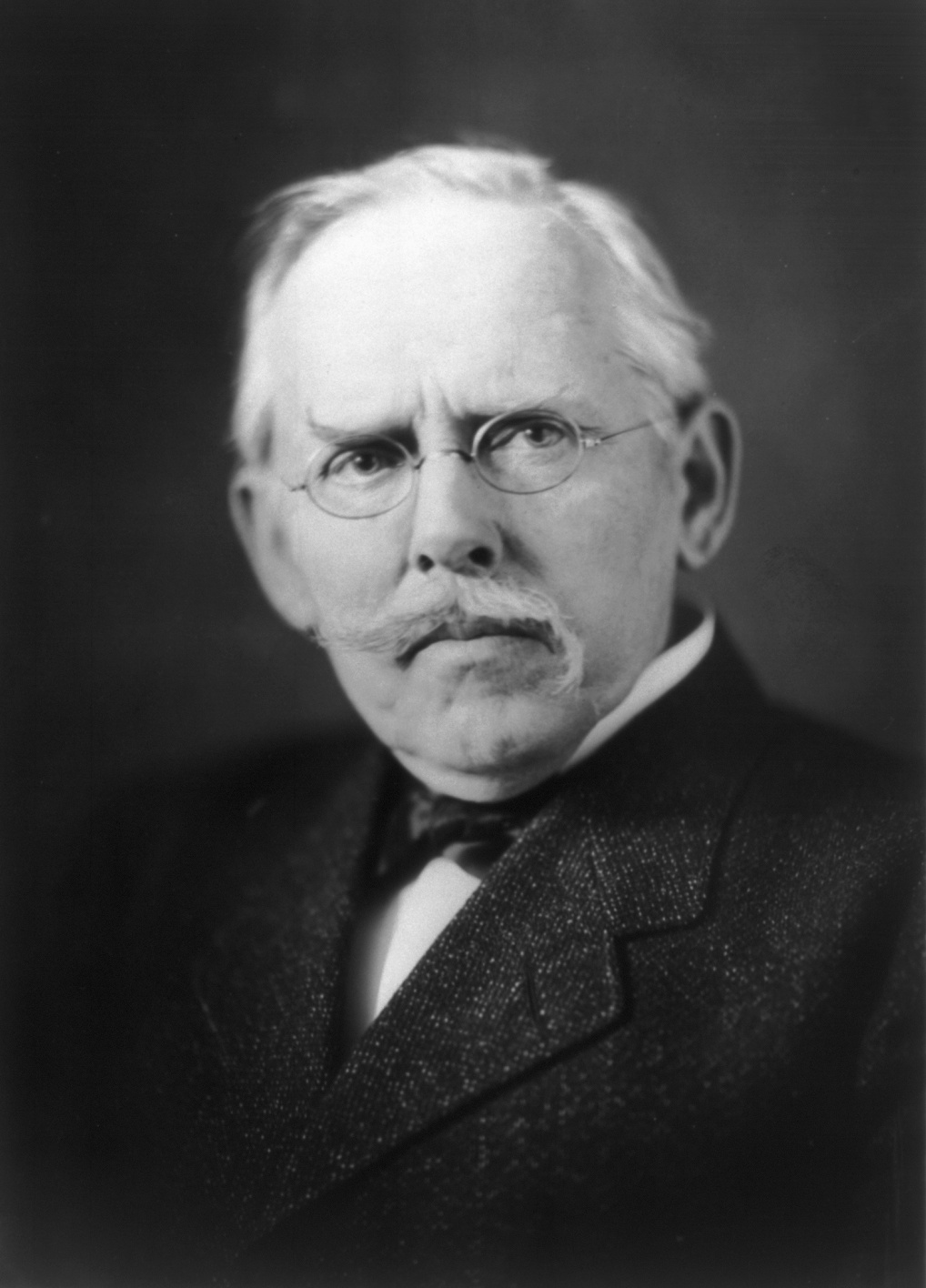

Mr. Roosevelt is a man of uncommon vigor. All his life he has sought work for the work’s sake. Position, like salary, he has not needed, and his strenuous spirit has put him in this category because he needed always to be doing. Neither did it matter much what the work was— assemblyman and rancher: civil service commissioner and historian; police commissioner and essayist; secretary of the navy and biographer; cavalry colonel, historian of his regiment, and candidate for governor; governor and hunter; vice president and then president—he has piled on the work, dropping the job done for the next with an avidity for the doing of things which has made him hardier and more eager than ever, president at the earliest age recorded in the place. Surely he is the man who of all others could carry the people’s burden and laugh at the toil. And he does laugh. But those nearest him say that the strain is beginning to be felt, and that he, even Theodore Roosevelt, is often weary.

An early riser and up betimes, he darts into the breakfast room with a cheerful hail to those already there, some of his family and a visitor or two. The visitors are confidential friends, and their interests are his. But his are government and politics. In other words, the day’s work is begun. By nine he is in his office, where he and Mr. George B. Cortelyou, the secretary to the president, are to have a quiet hour forecasting and planning the business before them. Mr. Cortelyou shows him the list of his appointments; the notes of bills, orders, and reports to come up, and such mail as he has to see. The president has to hurry because, as an exception (which occurs nearly every day), an appointment has been made before 10 o’clock, at 9.45; and it is 9.30 now.

Just then the President’s usher looks in. The president is indicating—not dictating, mind you (there is no time for that), but flashing hints of the replies he would make to the cream of his mail; and the secretary is making shorthand signs to recall them.

“Senator —,” says the usher; “important.”

The president waves to let Senator — come in, pelts some more hints at Mr. Cortelyou, and turns just in time to welcome his visitor. Before their hands have relaxed the grasp, the president and the senator are at it. It is important; and they go over it all, but at high speed. Before they are through another senator joins them, and by 9.45 the man with the special appointment is there. He hears the news; perhaps the others discuss it with him, and then go out leaving him to his special business. Before 10 o’clock other men with important and immediate business are there, and they drive one another on, while outside the crowd gathers.

On the White House door hangs a sign “Closed,” and two men in simple blue uniform guard the entrance. You go up to the door. “I wish to see the president,” you say.

The door is opened, and you pass up, following others, and followed by many more. Servants still are busy in the East Room; upstairs belated doorkeepers and clerks are hanging up their hats and overcoats. There are twenty people waiting in the hall; for if you are the public, you cannot go beyond, unless you have a special appointment; that is the rule. But you see many men and women filing in through the door to the office of the secretary to the president, and you send in your card. The doorkeeper nods an invitation to enter.

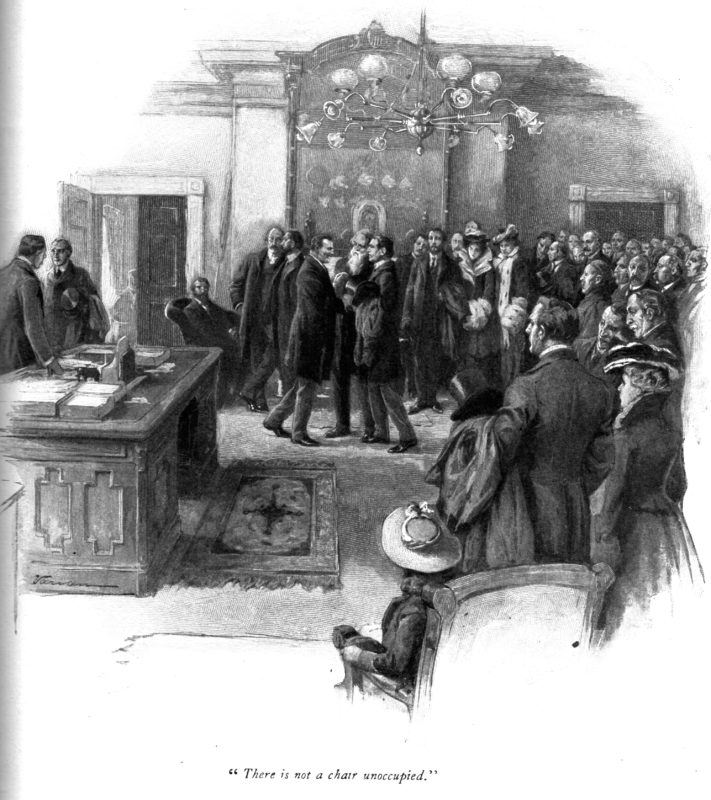

There is no chair unoccupied. The room is a large one, and chairs and sofas are set all about it; but they are filled, and many persons are standing. There are senators and representatives. They were admitted at once because it was their hour; but who are the other people—all these well-dressed men and shabby women? They are the constituents of the congressmen, who are breaking the rules established for their own convenience. They stand about in groups, some talking aloud and laughing, others whispering. Except for the dignified secretary standing at his desk, the scene is one of picturesque self-assurance, of a democratic holiday.

Time passes and more people come in. Ten o’clock comes and goes, and the secretary steps into the Cabinet room. You can see the president talking there with a new set of “important” visitors. You look about you and count again the relatively important visitors, fifty-three in all: seven senators, seventeen Representatives, two politicians and two police officers from New York, three women, two officers, and—the rest unclassified.

“I have here a constituent,” says a Representative to a senator, “who wants to see a live president,” and a good-natured hand claps the shoulder of a countryman abashed at the loudness of the introduction.

“Well,” the senator says from his armchair, “he’ll see the livest president we ever had.”

The Cabinet door opens and the president in a long frockcoat springs up the steps into the room. He looks about and halts. “I can’t see all these people, Mr. Cortelyou. I won’t. I cannot do it.” But his eye has been flashing about him, and in the window-seat spies a man he knows.

“Senator, I am glad to see you,” he says, and he seizes the senator’s hand. “I want to talk to you about—”

The senator turns to a man and a woman with him.

“Mr. President, I wish to present to you Mr. and Mrs. — They have come all the way —”

“I am glad to meet you. I am glad to meet you,” the president says to each of his new acquaintances, and his mind springs back to the business suggested by the sight of the senator. “Senator,” he says, “come in here with me. I want to see you about—”

He dives back into the Cabinet room, and the senator follows. The door slams shut and the crowd, which has been silent to gaze, rallies and takes up the conversation again by groups. More visitors file in, more Congressmen, more constituents. Then comes Admiral Evans, whom all know to have been summoned to talk over with the president the plans for the reception of Prince Henry of Prussia. When the president reappears, he comes as before with a leap and a pause, then steps out a few paces, and swings all the way around. He sees the Admiral, and seems about to hail him as he used to do before he was president, but he checks his arm and points it straight at Evans, who rises, and the arm points off to the Cabinet-room door. Admiral Evans disappears within, and the president goes up briskly to the first group. A senator is the center of it, and you expect to hear business; but no, it is constituents—a lot of them. The president shakes each by the hand, and to each says, “I am glad to see you,” “I am very glad to see you,” “I am very glad indeed to see you,” “It is a pleasure to meet you,” and so on, each greeting varying a little by word or accent. But the president is intent on something he has to say to that senator, and he pushes through up to him and carries him over to the fireplace, where they talk for a moment. Then the host fends away to some one else, striking out first for the faces he recognizes, usually those of Congressmen or officers of some department or branch of the service. Usually, too, the president has something serious to say, but rarely can he say it till he has “met” somebody. I wished the day I was there that not less but more Americans could have been there to see what the busiest man of us all was busied with.

It is some consolation to see that Mr. Roosevelt saves as many seconds as he can. He is very energetic, very brief with the people who “just want to see” him, and as soon as he has got at it he keeps the out-flowing stream ahead of that which is flowing in.

“Mr. President, I want you to meet Mr. —, a constituent of mine who only wants to see a live president.” It was the good-natured Representative with his farmer friend.

“I am very glad to meet you,” the president says, and he says it with a grasp of the hand and a cordiality that flashes conviction from his face, but it is only a flash. He drops the hand, his face sobers, and he moves off with the old senator who has called him “the livest president.” It is business again, and evidently it is important. They differ; there is a quick word from Mr. Roosevelt, and a slow shake of the older head, a ripping sentence, and a quiet answer; then:

“Think of it. senator, think it over, and we’ll talk about it another time.”

And that is done with; and yet this senator had business, real business with the president; you could tell by the way the president answered. When he speaks in a low, inaudible tone, you may be pretty sure that they are concerned with some matter of state; when, on the other hand, he has to meet requests that are matters not of state, but of politics, or worse, Mr. Roosevelt often speaks right out so that everybody hears. Petitioners whisper in vain; the answer is clear and distinct, and sometimes these answers are amusing to hear, seriously significant to reflect about afterwards.

They tell how one of the most eminent dignitaries of the government was among the callers one day. The president gave him precedence, expecting that his business was important, and the visitor did lean over and whisper most seriously. To the amazement and amusement of the knowing onlookers, the president’s reply aloud was:

“Mr. —, in the army, promotions go by seniority and merit alone.”

The dignitary whispered even more softly than before; but again the reply was:

“Mr. —, promotions in the army go by seniority and merit. It is a good practice, and I shall not interfere with it.”

Mr. — retreated, and the people who had heard told one another that he had in the army a son, who was very dear to him.

Another time it is related that a committee of New Englanders called to make some sort of a universal peace address. They presented their paper. Then they talked a bit. Finally one of them expressed a hope that the president’s known impetuosity would not lead him to make war unnecessarily. The president answered, with some impetuosity and some irony:

“You don’t suppose I’d want a war while I’m cooped up here in the White House, do you?”

The personal rebuke to General Miles occurred in just this way. The General was among the many visitors of a busy day, and, since it was delicate business, the president invited him to go into the Cabinet room. When General Miles insisted on an answer in the large room, he got it.

The day I was there such diversions were few. One Representative, however, drew the president into a corner and began to whisper.

“I told you,” said the president, interrupting aloud, “that you should take those claims to the Postmaster General.”

The flustered Congressman laid his hand on the president’s shoulder; but the answer was sharper than before. “Now, Congressman, you are only hurting your brother’s case. He will have his chance for the place when the present incumbent’s term is out. I have said I would not remove postmasters except for a cause and after a fair hearing; and I won’t.”

When the Representative spoke again he talked to the air, for the president was saying he was “very glad to meet you” to some one else.

The two police officers were next. They also whispered—at least one of them did, and he was pointing at the other, who looked meek. The president heard enough, and said very distinctly:

“I shall not interfere in the New York police force.”

Both officers drew up closer to him and buzzed very earnestly a second; but he cut them off, saying more loudly than before :

“You must see Mayor Low about that.”

They would have said more, but the president seized upon a senator, and with him retreated into the Cabinet room. He was gone for fully twenty minutes. When he returned the crowd seemed to be greater than ever, but the sight of it did not faze him this time. Pretty soon he came upon a man who had just “one word “ to say in favor of one candidate for an appointive office, as against all the rest of a large number of politicians involved in a small party squabble out in a western state. The office at stake was a petty one, but as “the future of the Republican party in that commonwealth depended upon the outcome of it,” the president was being appealed to decide among the factions. I knew personally of seven such disagreements in six different states that had been appealed to Mr. Roosevelt at about that time. Probably there were twice as many more before him which I knew nothing of. The politicians concerned could not understand why, in view of the importance of their own control, Mr. Roosevelt did not give them more time and attention. He did decide afterwards in three cases, and in these three left hard feelings among those against whom his decision fell; he refused to act in two, and caused hard feelings on both sides.

The president was now shaking hands so fast that he was rapidly reducing the crowd. Two persons he evidently wished to talk to he asked to precede him into the Cabinet room, and

at 1.30 he joined them there, leaving in the secretary’s room about a score of people who were invited to call the next day. Out in the anteroom was another crowd, and these also were bidden to call again.

The worst of the day’s work was over. If he had followed the day’s programme, he would have looked over the telegrams and important mail that had come in during the day, but there were his two remaining visitors to see, and after that he hurried off to luncheon with two other guests invited to that meal with him. After luncheon an unexpected visitor arrived, and not till this man was gone did the president and the secretary get down to some business that could not be postponed. It was three o’clock when the president retired for his daily exercise, a horseback ride. They say in Washington the president found he could not take walks without meeting some one who would stop him to shake hands, or join him to talk about business or politics, and that to get away from all this he has to go mounted. Yet his companion usually is some senator or government officer. In the interval between his return and dinner he goes over some more mail with his secretary, signs commissions, and, on my day, he received a report of the Isthmian Canal Commission. The evening was spent talking politics and state policies with an editor, two senators, and a well-known public man, all interested with him in politics. Toward the end of the session the late evening will probably be devoted to signing or vetoing bills. That was the time President Cleveland and President McKinley gave to such work, and Mr. Cleveland often stole time for strictly governmental business in the early mornings.

It is preposterous. Ex-Senator W. E. Chandler, who uttered a protest in a Washington newspaper, said: “The evil is a serious one, and cannot much longer be endured. It is injuring the public service by preventing the president from giving enough attention to large public questions. It is shortening the lives of the presidents. Unless a remedy is applied, few presidents will go through one term, and come out with health sufficient to allow the remainder of life to be enjoyable; no one will thus go through two terms.”

And Senator Chandler reviews the effect of this evil as he personally has observed it on other presidents. Lincoln was weakening under it when he was assassinated; President Hayes left the Presidency in poor health; Garfield “held office only four months, but long enough to lessen his vitality”; Arthur “ suffered unusually, left Washington in 1885 with low vitality, did not rally, and died in 1886”; “President Cleveland has seemed an exception—but four years of leisure intervened between his two terms; he has a strong constitution, is an imperturbable person, yet Mrs. Cleveland is now appealing to the public against a renewal of applications for all sorts of things which can hardly be considered even by a man in robust health”; President Harrison “had a good physique— he would have been spared longer if he had not undergone the inevitable strain of four years of the Presidency.”

Mr. Chandler described the change in President McKinley from the “elasticity and joyousness of the first term” to the “sadness and mere endurance” of the second term, and attributes his death indirectly to his bodily condition as the result of his long service in the White House.

The origin of this abuse was natural enough. George Washington had a sense not only of the dignity of the presidency, but of the use which a sentiment of deference toward the Chief Magistrate might have in a democracy; he received only people who had business with him or were his social or personal friends, and at public functions he stood with one hand on his sword-hilt, the other behind his back. A very intimate friend of his who dared, on a wager, to lay a hand on his shoulder was severely snubbed. After Washington, many of the forms which he established were observed, though with ever-lessening rigidity, until Andrew Jackson swept them all away

and opened his house to everybody. There was some excuse for Jackson. In those days there was a strong tendency in some parts of the country toward aristocracy. Moreover, transportation was difficult, slow, and expensive then, and even to Jackson’s open house no great crowds came. Those who traveled to the Capitol to see the president usually had some motive stronger than curiosity. They may have come on politics; indeed, we know that much of it was low and trivial politics; but none came “just to see a live president,” or “just to shake hands.” So it was down to the Civil War. With that crisis, business of all kinds increased at the White House; the president had a great war and most difficult foreign relations to handle; he had politics and war politics, besides all the intense legislative activity consequent upon war. After that the business did not lessen; it increased, and the open-house policy of Jackson went on becoming more and more ridiculous, while the new railroads poured in such crowds as “Old Hickory” never dreamed of. General Grant’s hand was shaken till it swelled. “He did not know how to shake hands,” a senator explained to me. “A president must learn to rush up, seize and grasp the other man’s hand; he should never let the other man get the first grip and squeeze him.” What an art for a president to have to learn!

But it is not alone the president that suffers. Public business, the interests of the people, lose more by it than the man who happens to be at the head of the nation. Perhaps Mr. Roosevelt can stand it; he can if anybody can. But as things are going now, one-third of his working day of ten hours is given mainly to business worse than trivial. It is an abuse of democratic privilege. Moreover, this third of all his time is the best part of it, the morning stretch from 10 till 2; the rest is broken up by luncheon, dinner, and recreation.

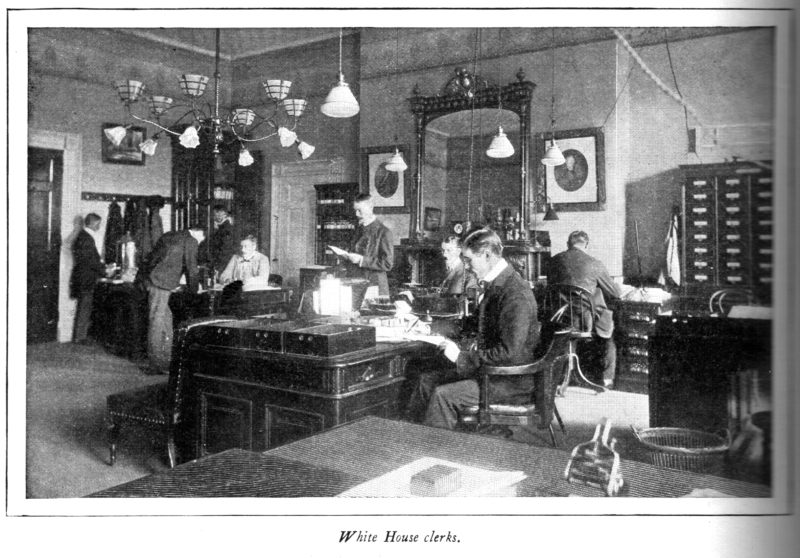

There must be some remedy for the evil, and Washington is beginning to take the matter up seriously. A bill was introduced this session to provide a separate building for the executive officers and the president and his staff, which has increased from one secretary, two doormen, two furnace-keepers, and a watchman, to one secretary, two assistant secretaries, nine clerks, six messengers, five ushers regularly employed, and eleven clerks and six messengers loaned to the White House by departments. It keeps one man and four clerks busy handling social invitations. The mail amounts to 1,000 or 1,200 letters a day. The executive building would relieve the president and his family of the inconvenience and the indignity of living “over the shop”; it might spare them the visits of sightseers; there would be more room for home and social functions and for business, too; and the president could get some fresh air and exercise passing between his house and office. The separation of the president’s home from his office seems to be inevitable, but it will not entirely solve the problem. Much more remains to be done.

Senator Chandler suggests an assistant president, but that is coming gradually in the growing functions of the Secretary to the president. Formerly called the private secretary, this official has always had much of the president’s work to do, and some of his power; but the personalities of some of the recent secretaries, especially John Hay and Daniel S. Lament, have enlarged the scope and importance of the position, till now under Mr. Cortelyou we hear it spoken of as “tantamount to a seat in the Cabinet.” Mr. Cortelyou certainly performs a vast amount of important and delicate service, so that he is more truly assistant to the president than a mere secretary. He has attacked the problem of an impossible amount of business for one man, and has reduced the mail that goes to Mr. Roosevelt personally to about one one-hundredth of the whole. A large part of it is forwarded to departments without executive acknowledgment or even a record being taken of its receipt. The secretary himself conducts most of the correspondence, and the older Congressmen will tell you that they would rather put their business into the hands of the deliberate, painstaking, tactful secretary than in those of the overworked and hurried president.

The Congressmen who take their constituents or their cases to the president personally either are green, or they wish to shift the responsibility from their own upon broader shoulders. And it is the Congressmen’s abuse of their privileged two hours a day that is the most hopeless feature of the situation. No secretary can shut them out. But they can be reduced to reason, and the way suggested is to forbid them to introduce constituents, except with consent; to require them when they call to approach the president only on political or state business, and then through the head of a department, and the meeting with the president shall be by special appointment on the day when all the papers of the case shall have been prepared and summarized by the secretary. As to citizens, no citizen should be admitted, except by appointment previously made by correspondence with the secretary. This would shift to the secretary a large part of the labor of the Presidency, and to heads of departments most of the small politics. It is this urgent and necessary reform to which Secretary Cortelyou is now giving his best endeavors.

The man to solve the whole problem, however, is the president; not any president, but President Roosevelt. The reform must be established by the will of a strong man who is truly democratic and not afraid of a fight. A president who was physically weak might be excused for closing his doors, but he could not thus set a binding precedent. The rule must be laid down by a man who may back it up by saying, “I can, but I won’t stand it.” And when the politicians cry out against him, and the statesmen slip out of the way of the blame; when the sightseers and bridal couples complain and the committees of merchants denounce, he must appeal to the many people with the great common interest against the vain and curious few. There is no doubt about the democracy of President Roosevelt; it lies as deep as his courage, and rises as high as his ambition; none would accuse him of exclusiveness or aristocratic leanings. If he should say that he needed time to study, think, and deliberately decide on public measures; that a week divided into two days for affairs of state, and four for politics and handshaking was not fair to him or to the people; if he should prefer the precedent of Washington over that of Jackson, it is likely that he would receive the popular support of American common sense.