Paolo’s Awakening

Paolo’s Awakening

• While the dread and uncertainty grew, a messenger ran up, out of breath. There had been a collision. The last train had run into the one preceding it, in the fog.

Paolo’s Awakening

By Jacob Riis

PAOLO sat cross-legged on his bench, stitching away for dear life. He pursed his lips and screwed up his mouth into all sorts of odd shapes with the effort, for it was an effort. He was only eight, and you would scarcely have imagined him over six, as he sat there sewing like a real little tailor; only Paolo knew but one seam, and that a hard one. Yet he held the needle and felt the edge with it in quite a grown-up way, and pulled the thread just as far as his short arm would reach. His mother sat on a stool by the window, where she could help him when he got into a snarl,—as he did once in a while, in spite of all he could do,—or when the needle had to be threaded. Then she dropped her own sewing, and, patting him on the head, said he was a good boy.

Paolo felt very proud and big then, that he was able to help his mother, and he worked even more carefully and faithfully than before, so that the boss should find no fault. The shouts of the boys in the block, playing duck-on-a-rock down in the street, came in through the open window, and he laughed as he heard them. He did not envy them, though he liked well enough to romp with the others. His was a sunny temper, content with what came; besides, his supper was at stake, and Paolo had a good appetite. They were in sober earnest working for dear life—Paolo and his mother.

“Pants” for the sweater in Stanton street was what they were making; little knickerbockers for boys of Paolo’s own age. “Twelve pants for ten cents,” he said, counting on his fingers. The mother brought them once a week—a big bundle which she carried home on her head—to have the buttons put on, fourteen on each pair, the bottoms turned up, and a ribbon sewed fast to the back seam inside. That was called finishing. When work was brisk—and it was not always so since there had been such frequent strikes in Stanton street—they could together make the rent-money, and even more, as Paolo was learning and getting a stronger grip on the needle week by week. The rent was six dollars a month for a dingy basement room, in which it was twilight even on the brightest days, and a dark little cubbyhole, where it was always midnight, and where there was just room for a bed of old boards, no more. In there slept Paolo with his uncle; his mother made her bed on the floor of the “kitchen,” as they called it.

The three made the family. There used to be four; but one stormy night in winter Paolo’s father had not come home. The uncle came alone, and the story he told made the poor home in the basement darker and drearier for many a day than it had yet been. The two men worked together for a padrone on the scows. They were in the crew that went out that day to the dumping-ground, far outside the harbor. It was a dangerous journey in a rough sea. The half-frozen Italians clung to the great heaps like so many frightened flies, when the waves rose and tossed the unwieldy scows about, bumping one against the other, though they were strung out in a long row behind the tug, quite a distance apart. One sea washed entirely over the last scow and nearly upset it. When it floated even again, two of the crew were missing, one of them Paolo’s father. They had been washed away and lost, miles from shore. No one ever saw them again.

The widow’s tears flowed for her dead husband, whom she could not even see laid in a grave which the priest had blessed. The good father spoke to her of the sea as a vast God’s-acre, over which the storms are forever chanting anthems in his praise to whom the secrets of its depths are revealed; but she thought of it only as the cruel destroyer that had robbed her of her husband, and her tears fell faster. Paolo cried, too: partly because his mother cried; partly, if the truth must be told, because he was not to have a ride to the cemetery in the splendid coach. Giuseppe Salvatore, in the corner house, had never ceased talking of the ride he had when his father died, the year before. Pietro and Jim went along, too, and rode all the way behind the hearse with black plumes. It was a sore subject with Paolo, for he was in school that day.

The widow’s tears flowed for her dead husband, whom she could not even see laid in a grave which the priest had blessed. The good father spoke to her of the sea as a vast God’s-acre, over which the storms are forever chanting anthems in his praise to whom the secrets of its depths are revealed; but she thought of it only as the cruel destroyer that had robbed her of her husband, and her tears fell faster. Paolo cried, too: partly because his mother cried; partly, if the truth must be told, because he was not to have a ride to the cemetery in the splendid coach. Giuseppe Salvatore, in the corner house, had never ceased talking of the ride he had when his father died, the year before. Pietro and Jim went along, too, and rode all the way behind the hearse with black plumes. It was a sore subject with Paolo, for he was in school that day.

And then he and his mother dried their tears and went to work. Henceforth there was to be little else for them. The luxury of grief is not among the few luxuries which Mott-street tenements afford. Paolo’s life, after that, was lived mainly with the pants on his hard bench in the rear tenement. His routine of work was varied by the household duties, which he shared with his mother. There were the meals to get, few and plain as they were. Paolo was the cook, and not infrequently, when a building was being torn down in the neighborhood, he furnished the fuel as well. Those were his off days, when he put the needle away and foraged with the other children, dragging old beams and carrying burdens far beyond his years.

The truant officer never found his way to Paolo’s tenement to discover that he could neither read nor write, and, what was more, would probably never learn. It would have been of little use, for the public schools thereabouts were crowded, and Paolo could not have got into one of them if he had tried. The teacher from the Industrial School, which he had attended for one brief season while his father was alive, called at long intervals, and brought him once a plant, which he set out in his mother’s window-garden and nursed carefully ever after. The “garden” was contained within an old starch-box, which had its place on the window-sill since the policeman had ordered the fire-escape to be cleared. It was a kitchen-garden with vegetables, and was almost all the green there was in the landscape. From one or two other windows in the yard there peeped tufts of green; but of trees there was none in sight—nothing but the bare clothes-poles with their pulley-lines stretching from every window.

Beside the cemetery plot in the next block there was not an open spot or breathing-place, certainly not a playground, within reach of that great teeming slum that harbored more than a hundred thousand persons, young and old. Even the graveyard was shut in by a high brick wall, so that a glimpse of the greensward over the old mounds was to be caught only through the spiked iron gates, the key to which was lost, or by standing on tiptoe and craning one’s neck. The dead there were of more account, though they had been forgotten these many years, than the living children who gazed so wistfully upon the little paradise through the barred gates, and were chased by the policeman when he came that way. Something like this thought was in Paolo’s mind when he stood at sunset and peered in at the golden rays falling athwart the green, but he did not know it. Paolo was not a philosopher, but he loved beauty and beautiful things, and was conscious of a great hunger which there was nothing in his narrow world to satisfy.

Certainly not in the tenement. It was old and rickety and wretched, in keeping with the slum of which it formed a part. The whitewash was peeling off the walls, the stairs were patched, and the door-step long since worn entirely away. It was hard to be decent in such a place, but the widow did the best she could. Her rooms were as neat as the general dilapidation would permit. On the shelf where the old clock stood, flanked by the best crockery, most of it cracked and yellow with age, there was red and green paper cut in scallops very nicely. Garlic and onions hung in strings over the stove, and the red peppers that grew in the starch-box at the window gave quite a cheerful appearance to the room. In the corner, under a cheap print of the Virgin Mary with the Child, a small night-light in a blue glass was always kept burning. It was a kind of illumination in honor of the Mother of God, through which the widow’s devout nature found expression. Paolo always looked upon it as a very solemn show. When he said his prayers, the sweet, patient eyes in the picture seemed to watch him with a mild look that made him turn over and go to sleep with a sigh of contentment. He felt then that he had not been altogether bad, and that he was quite safe in their keeping.

Yet Paolo’s life was not wholly without its bright spots. Far from it. There were the occasional trips to the dump with Uncle Pasquale’s dinner, where there was always sport to be had in chasing the rats that overran the place, fighting for the scraps and bones the trimmers had rescued from the scows. There were so many of them, and so bold were they, that an old Italian who could no longer dig was employed to sit on a bale of rags and throw things at them, lest they carry off the whole establishment. When he hit one, the rest squealed and scampered away; but they were back again in a minute, and the old man had his hands full pretty nearly all the time. Paolo thought that his was a glorious job, as any boy might, and hoped that he would soon be old, too, and as important. And then the men at the cage—a great wire crate into which the rags from the ash-barrels were stuffed, to be plunged into the river, where the tide ran through them and carried some of the loose dirt away. That was called washing the rags. To Paolo it was the most exciting thing in the world. What if some day the crate should bring up a fish, a real fish, from the river? When he thought of it, he wished that he might be sitting forever on that string-piece, fishing with the rag-cage, particularly when he was tired of stitching and turning over, a whole long day.

Besides, there were the real holidays, when there was a marriage, a christening, or a funeral in the tenement, particularly when a baby died whose father belonged to one of the many benefit societies. A brass band was the proper thing then, and the whole block took a vacation to follow the music and the white hearse out of their ward into the next. But the chief of all the holidays came once a year, when the feast of St. Rocco—the patron saint of the village where Paolo’s parents had lived—was celebrated. Then a really beautiful altar was erected at one end of the yard, with lights and pictures on it. The rear fire-escapes in the whole row were decked with sheets, and made into handsome balconies,—reserved seats, as it were,—on which the tenants sat and enjoyed it. A band in gorgeous uniforms played three whole days in the yard, and the men in their holiday clothes stepped up, bowed, and crossed themselves, and laid their gifts on the plate which St. Rocco’s namesake, the saloon-keeper in the block, who had got up the celebration, had put there for them. In the evening they set off great strings of fire-crackers in the street, in the saint’s honor, until the police interfered once and forbade that. Those were great days for Paolo always.

But the fun Paolo loved best of all was when he could get in a corner by himself, with no one to disturb him, and build castles and things out of some abandoned clay or mortar, or wet sand if there was nothing better. The plastic material took strange shapes of beauty under his hands. It was as if life had been somehow breathed into it by his touch, and it ordered itself as none of the other boys could make it. His fingers were tipped with genius, but he did not know it, for his work was only for the hour. He destroyed it as soon as it was made, to try for something better. What he had made never satisfied him—one of the surest proofs that he was capable of great things, had he only known it. But, as I said, he did not.

The teacher from the Industrial School came upon him one day, sitting in the corner by himself, and breathing life into the mud. She stood and watched him awhile, unseen, getting interested, almost excited, as he worked on. As for Paolo, he was solving the problem that had eluded him so long, and had eyes or thought for nothing else. As his fingers ran over the soft clay, the needle, the hard bench, the pants, even the sweater himself, vanished out of his sight, out of his life, and he thought only of the beautiful things he was fashioning to express the longing in his soul, which nothing mortal could shape. Then, suddenly, seeing and despairing, he dashed it to pieces, and came back to earth and to the tenement.

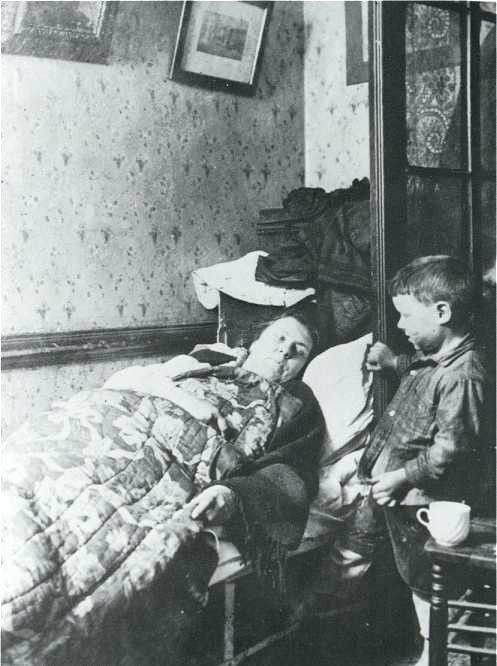

But not to the pants and the sweater. What the teacher had seen that day had set her to thinking, and her visit resulted in a great change for Paolo. She called at night and had a long talk with his mother and uncle through the medium of the priest, who interpreted when they got to a hard place. Uncle Pasquale took but little part in the conversation. He sat by and nodded most of the time, assured by the presence of the priest that it was all right. The widow cried a good deal, and went more than once to take a look at the boy, lying snugly tucked in his bed in the inner room, quite unconscious of the weighty matters that were being decided concerning him. She came back the last time drying her eyes, and laid both her hands in the hand of the teacher. She nodded twice and smiled through her tears, and the bargain was made. Paolo’s slavery was at an end.

His friend came the next day and took him away, dressed up in his best clothes, to a large school where there were many children, not of his own people, and where he was received kindly. There dawned that day a new life for Paolo, for in the afternoon trays of modeling-clay were brought in, and the children were told to mold in it objects that were set before them. Paolo’s teacher stood by, and nodded approvingly as his little fingers played so deftly with the clay, his face all lighted up with joy at this strange kind of a school-lesson.

After that he had a new and faithful friend, and, as he worked away, putting his whole young soul into the tasks that filled it with radiant hope, other friends, rich and powerful, found him out in his slum. They brought better-paying work for his mother than sewing pants for the sweater, and Uncle Pasquale abandoned the scows to become a porter in a big shipping-house on the West Side. The little family moved out of the old home into a better tenement, though not far away. Paolo’s loyal heart clung to the neighborhood where he had played and dreamed as a child, and he wanted it to share in his good fortune, now that it had come. As the days passed, the neighbors who had known him as little Paolo came to speak of him as one who some day would be a great artist and make them all proud. He laughed at that, and said that the first bust he would hew in marble should be that of his patient, faithful mother; and with that he gave her a little hug, and danced out of the room, leaving her to look after him with glistening eyes, brimming over with happiness.

But Paolo’s dream was to have another awakening. The years passed and brought their changes. In the manly youth who came forward as his name was called in the academy, and stood modestly at the desk to receive his diploma, few would have recognized the little ragamuffin who had dragged bundles of fire-wood to the rookery in the alley, and carried Uncle Pasquale’s dinner-pail to the dump. But the audience gathered to witness the commencement exercises knew it all, and greeted him with a hearty welcome that recalled his early struggles and his hard-won success. It was Paolo’s day of triumph. The class honors and the medal were his. The bust that had won both stood in the hall crowned with laurel—an Italian peasant woman, with sweet, gentle face, in which there lingered the memories of the patient eyes that had lulled the child to sleep in the old days in the alley. His teacher spoke to him, spoke of him, with pride in voice and glance; spoke tenderly of his old mother of the tenement, of his faithful work, of the loyal manhood that ever is the soul and badge of true genius. As he bade him welcome to the fellowship of artists who in him honored the best and noblest in their own aspirations, the emotion of the audience found voice once more. Paolo, flushed, his eyes filled with happy tears, stumbled out, he knew not how, with the coveted parchment in his hand.

Home to his mother! It was the one thought in his mind as he walked toward the big bridge to cross to the city of his home—to tell her of his joy, of his success. Soon she would no longer be poor. The day of hardship was over. He could work now and earn money, much money, and the world would know and honor Paolo’s mother as it had honored him. As he walked through the foggy winter day toward the river, where delayed throngs jostled one another at the bridge entrance, he thought with grateful heart of the friends who had smoothed the way for him. Ah, not for long the fog and slush! The medal carried with it a traveling stipend, and soon the sunlight of his native land for him and her. He should hear the surf wash on the shingly beach and in the deep grottoes of which she had sung to him when a child. Had he not promised her this? And had they not many a time laughed for very joy at the prospect, the two together?

He picked his way up the crowded stairs, carefully guarding the precious roll. The crush was even greater than usual. There had been delay—something wrong with the cable; but a train was just waiting, and he hurried on board with the rest, little heeding what became of him so long as the diploma was safe. The train rolled out on the bridge,with Paolo wedged in the crowd on the platform of the last car, holding the paper high over his head, where it was sheltered safe from the fog and the rain and the crush.

Another train backed up, received its load of cross humanity, and vanished in the mist. The damp gray curtain had barely closed behind it, and the impatient throng was fretting at a further delay, when consternation spread in the bridge-house. Word had come up from the track that something had happened. Trains were stalled all along the route. While the dread and uncertainty grew, a messenger ran up, out of breath. There had been a collision. The last train had run into the one preceding it, in the fog. One was killed, others were injured. Doctors and ambulances were wanted.

They came with the police, and by and by the partly wrecked train was hauled up to the platform. When the wounded had been taken to the hospital, they bore from the train the body of a youth, clutching yet in his hand a torn, blood-stained paper, tied about with a purple ribbon. It was Paolo. The awakening had come. Brighter skies than those of sunny Italy had dawned upon him in the gloom and terror of the great crash. Paolo was at home, waiting for his mother.