Rover’s Last Fight

Rover’s Last Fight

• The house of Gabriel Dodge, a well-to-do farmer, had been sacked by thieves, who left in their trail the farmer’s murdered dog.

Rover’s Last Fight

By Jacob Riis

From Out of Mulberry Street

THE little village of Valley Stream nestles peacefully among the woods and meadows of Long Island. The days and the years roll by uneventfully within its quiet precincts. Nothing more exciting than the arrival of a party of fishermen from the city, on a vain hunt for perch in the ponds that lie hidden among its groves and feed the Brooklyn water-works, troubles the every-day routine of the village. Two great railroad wrecks are remembered thereabouts, but these are already ancient history. Only the oldest inhabitants know of the earlier one. There hasn’t been as much as a sudden death in the town since, and the constable and chief of police—probably one and the same person—haven’t turned an honest or dishonest penny in the whole course of their official existence. All of which is as it ought to be.

But at last something occurred that ought not to have been. The village was aroused at daybreak by the intelligence that a robbery had been committed overnight, and a murder. The house of Gabriel Dodge, a well-to-do farmer, had been sacked by thieves, who left in their trail the farmer’s murdered dog. Rover was a collie, large for his kind, and quite as noisy as the rest of them. He had been left as an outside guard, according to Farmer Dodge’s awkward practice. Inside, he might have been of use by alarming the folks when the thieves tried to get in. But they had only to fear his bark; his bite was harmless.

The whole of Valley Stream gathered at Farmer Dodge’s house to watch, awe-struck, the mysterious movements of the police force as it went tiptoeing about, peeping into corners, secretly examining tracks in the mud, and squinting suspiciously at the brogans of the bystanders. When it had all been gone through, this record of facts bearing on the case was made:

Rover was dead.

He had apparently been smothered.

With the hand, not a rope.

There was a ladder set up against the window of the spare bedroom.

That it had not been there before was evidence that the thieves had set it up.

The window was open, and they had gone in.

Several watches, some good clothes, sundry articles of jewelry, all worth some six or seven hundred dollars, were missing and could not be found.

In conclusion, the constable put on record his belief that the thieves who had smothered the dog and set up the ladder had taken the property.

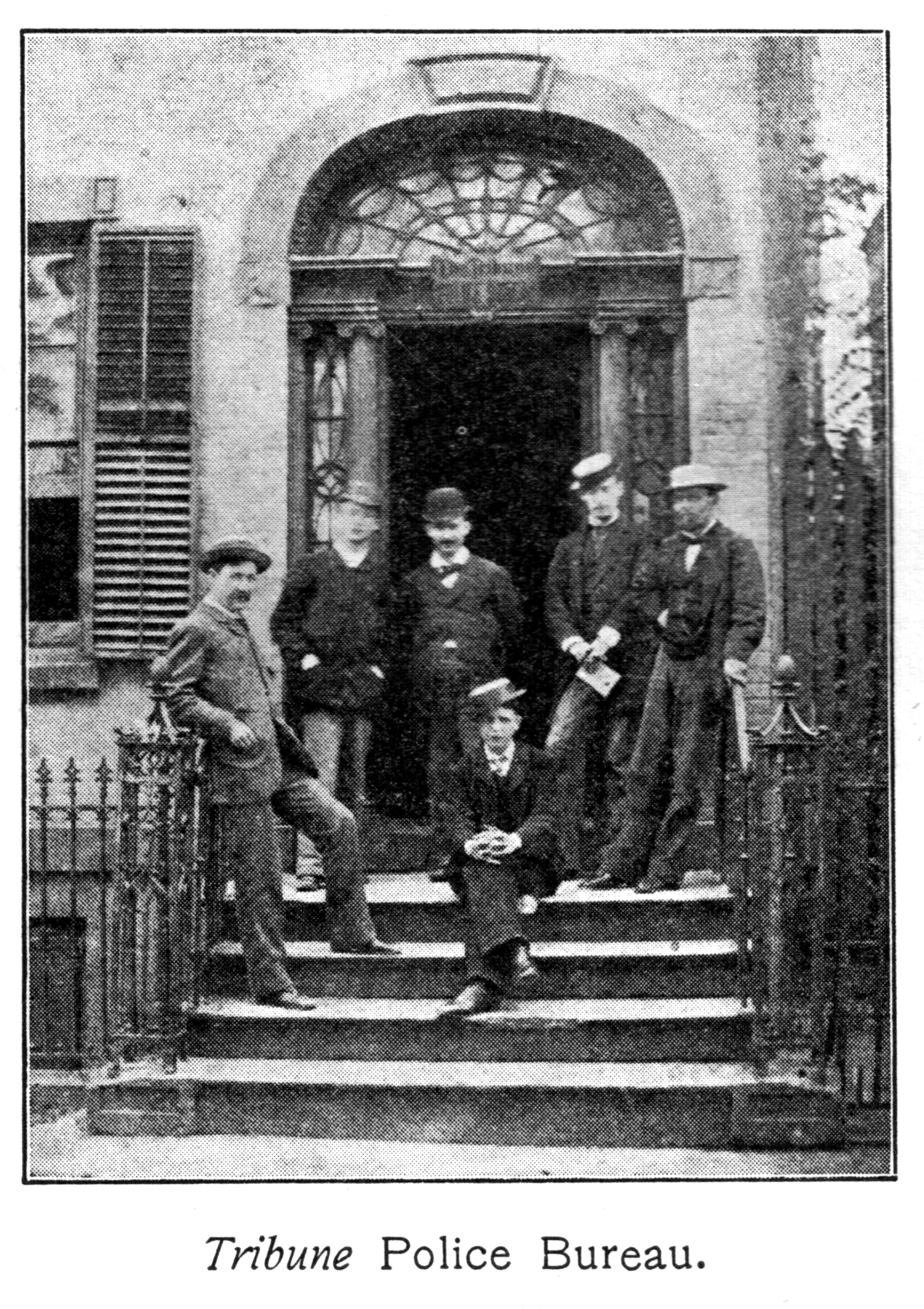

The solid citizens of the village sat upon the verdict in the store, solemnly considered it, and agreed that it was so. This point settled, there was left only the other: Who were the thieves? The solid citizens by a unanimous decision concluded that Inspector Byrnes was the man to tell them.

So they came over to New York and laid the matter before him, with a mental diagram of the village, the house, the dog, and the ladder at the window. There was just the suspicion of a twinkle in the corner of the inspector’s eye as he listened gravely and then said:

“It was the spare bedroom, wasn’t it?”

“The spare bedroom,” said the committee, in one breath.

“The only one in the house?” queried the inspector, further.

“The only one,” responded the echo.

“H’m!” pondered the inspector. “You keep hands on your farm, Mr. Dodge?”

Mr. Dodge did.

“Sleep in the house?”

“Yes.”

“Discharged any one lately?”

The committee rose as one man, and, staring at each other with bulging eyes, said “Jake!” all at once.

“Jakey, b’ gosh!” repeated the constable to himself, kicking his own shins softly as he tugged at his beard. “Jake, by thunder!”

Jake was a boy of eighteen, who had been employed by the farmer to do chores. He was shiftless, and a week or two before had been sent away in disgrace. He had gone no one knew whither.

The committee told the inspector all about Jake, gave him a minute description of him,—of his ways, his gait, and his clothes,—and went home feeling that they had been wondrous smart in putting so sharp a man on the track he would never have thought of if they hadn’t mentioned Jake’s name. All he had to do now was to follow it to the end, and let them know when he had reached it. And as these good men had prophesied, even so it came to pass.

Detectives of the inspector’s staff were put on the trail. They followed it from the Long Island pastures across the East River to the Bowery, and there into one of the cheap lodging-houses where thieves are turned out ready-made while you wait. There they found Jake.

They didn’t hail him at once, or clap him into irons, as the constable from Valley Stream would have done. They let him alone and watched awhile to see what he was doing. And the thing that they found him doing was just what they expected: he was herding with thieves. When they had thoroughly fastened this companionship upon the lad, they arrested the band. They were three.

They had not been locked up many hours at Headquarters before the inspector sent for Jake. He told him he knew all about his dismissal by Farmer Dodge, and asked him what he had done to the old man. Jake blurted out hotly, “Nothin’,” and betrayed such feeling that his questioner soon made him admit that he was “sore on the boss.” From that to telling the whole story of the robbery was only a little way, easy to travel in such company as Jake was in then. He told how he had come to New York, angry enough to do anything, and had “struck” the Bowery. Struck, too, his two friends, not the only two of that kind who loiter about that thoroughfare.

To them he told his story while waiting in the “hotel” for something to turn up, and they showed him a way to get square with the old man for what he had done to him. The farmer had money and property he would hate to lose. Jake knew the lay of the land, and could steer them straight; they would take care of the rest. “See!” said they.

Jake saw, and the sight tempted him. But in his mind’s eye he saw also Rover and heard him bark. How could he be managed?

“He will come to me if I call him,” pondered Jake, while his two companions sat watching his face, “but you may have to kill him. Poor Rover!”

“You call the dog and leave him to me,” said the oldest thief, and shut his teeth hard. And so it was arranged.

That night the three went out on the last train, and hid in the woods down by the gatekeeper’s house at the pond, until the last light had gone out in the village and it was fast asleep. Then they crept up by a back way to Farmer Dodge’s house. As expected, Rover came bounding out at their approach, barking furiously. It was Jake’s turn then.

“Rover,” he called softly, and whistled. The dog stopped barking and came on, wagging his tail, but still growling ominously as he got scent of the strange men.

“Rover, poor Rover,” said Jake, stroking his shaggy fur and feeling like the guilty wretch he was; for just then the hand of Pfeiffer, the thief, grabbed the throat of the faithful beast in a grip as of an iron vise, and he had barked his last bark. Struggle as he might, he could not free himself or breathe, while Jake, the treacherous Jake, held his legs. And so he died, fighting for his master and his home.

In the morning the ladder at the open window and poor Rover dead in the yard told of the drama of the night.

The committee of farmers came over and took Jake home, after congratulating Inspector Byrnes on having so intelligently followed their directions in hunting down the thieves. The inspector shook hands with them and smiled.